John R. Nelson

Note: This article is an expanded version of “Thomas Nuttall: Pioneering Naturalist” published in the May/June 2015 issue of Harvard Magazine.

Portrait of Nuttall, artist unknown—probably the only known portrait.

Thomas Nuttall’s first love was plants, not birds. In 1808, the day after he came to Philadelphia from his native England, Nuttall saw a common greenbrier, a species unknown to him, and brought it to Benjamin Smith Barton, professor of Natural History and Botany at the University of Pennsylvania. Barton, author of the first American botany textbook, was struck by the young man’s fervor for plants and became his mentor. Two years later, he sent Nuttall on the first of his many great collecting expeditions: west to the Great Lakes, up the Missouri River into Mandan territory in North Dakota, and then down the Mississippi.

Despite identification papers signed by President Madison, Nuttall soon realized that he wouldn’t be welcomed by British trappers who controlled the Great Lakes region, and he joined a John Jacob Astor fur trading party on Mackinac Island. In woods and prairies along the wide Missouri, he found plants new to science and collected species discovered, but lost in transit, by the Lewis and Clark expedition. Mishaps punctuated his single-minded scientific quest. Suffering chills and fever from malaria, he had to be rescued by a Mandan after he’d wandered off and collapsed on the plains. Later, lost again, he fled from the Indians who’d been sent to save him but were wary of approaching him because of his reputation for brewing powerful herbal concoctions. He entrusted another group of Indians to deliver specimens by boat, only to be told that his couriers drank the alcohol used to preserve his treasures.

In late 1811, at journey’s end in New Orleans, Nuttall, apparently worried about the prospect of imminent war with England, boarded a ship for London, but he soon returned to Philadelphia. Though Barton had warned him to safeguard his specimens from piratical naturalists, Nuttall learned that Frederick Pursh, Barton’s previous assistant, had managed to access much of his collection, adding Nuttall’s species—and naming some after himself—in an appendix to his 1814 book on North American plants (Hanley 1977). Undaunted, Nuttall headed off in 1816 on his second major collecting expedition, traveling by boat down the Ohio River and then trekking alone across Kentucky and Tennessee, returning north through the Carolinas. An apprentice printer back home in Yorkshire, Nuttall published his first major work at his own expense in 1818. Renowned botanist John Torrey declared that the book, The Genera of North American Plants and a Catalogue of the Species, to the Year 1817, “contributed more than any other work to advance the accurate knowledge of the plants in this country.” (Southwest Colorado Wildflowers 2015)

Nuttall had gained the respect of fellow botanists, but to the public at large, he had also become a prototype of the absent-minded professor, the naturalist as nerd. He first appeared in narratives of the Astor expeditions by Henry Breckenridge and John Bradley, who mocked his impassioned gathering of “weeds,” comical obliviousness to danger, inability to swim, and his use of his rifle to store seeds. In Astoria, Washington Irving labeled Nuttall a “zealous botanist” who went “groping and stumbling along among a wilderness of sweets, forgetful of everything but his immediate pursuit,….The Canadian voyageurs… used to make merry at his expense, regarding him as some whimsical kind of madman.” (Kastner 1977) Historian Joseph Kastner calls him “a throwback to that bemused figure of the Middle Ages, the Blessed Fool, who, protected by his own innocence, wandered unharmed from one peril to the next.” (Kastner 1977) He may even have been the inspiration for Dr. Obed Bat, the obsessive blowhard naturalist satirized in James Fenimore Cooper’s 1827 novel The Prairie. Although there is no evidence that the two men ever met, Cooper did know Irving’s Astoria. But if Bat is a fictionalized Nuttall, or a composite of weed-bat-bug-bird-gathering naturalists, this and the other caricatures, however amusing, seem ungenerous and small-minded in their view of scientific exploration. Preoccupied Nuttall may have been, even pompous and pedantic, and he certainly got lost a lot, but there’s no doubting his endurance and relentless determination to discover and understand the natural wonders of the American West as a pioneer in the study of the continent’s flora and fauna.

Nuttall showed his tenacity in 1818 when, after failing to procure funding for an expedition, he set off anyway on his third major journey, to the Southwest, a region then virtually unknown to naturalists. Traveling by flatboat, on horseback, and on foot, he covered over 5000 miles, heading down the Ohio and Mississippi, going up the Arkansas River beyond the army posts and into Comanche territory, and then making his way to New Orleans. He recounted his journey in his 1821 A Journal of Travels into the Arkansas Territory. Sensitive to criticism, Nuttall complained in the preface that his work had often met with “detraction and envy” instead of gratitude, and he insisted that he hadn’t written the Journal for “emolument” but rather had “sacrificed both time and fortune to it.” The book, he claimed, wasn’t intended for “those who vaguely peruse the narratives of travelers for pastime or transitory amusement” but for “the scientific part of the community.” “To converse, as it were, with nature,” he wrote, “to admire the wisdom and beauty of creation, has ever been, and I hope ever will be, to me a favorite pursuit.” (Nuttall 1821)

Photo of Nuttall Club, 1889, from the Library of Congress

The Journal captures Nuttall’s excitement at finding almost countless new plant varieties, and the wonder of Arkansas’s dawn chorus—“the songs of thousands of birds, re-echoing through the woods.” But whatever his intent, the book reads like an epic adventure yarn, as Nuttall must overcome one obstacle after another, some natural, others human: floating ice, hidden sand bars, and treacherous eddies on the Mississippi; swampy, mosquito-infested forests in Arkansas; “pathless” and “inhospitable” deserts; drunken, unreliable boatmen; pirate gangs and “swindling robbers” on the river banks and islands; yellow fever; foul water; wormy meat; blow-flies and their maggots; freezing cold; and remorseless heat. Anticipating the time when “civilized society” would come to the “luxuriant wilds” of the West, Nuttall hardly romanticizes wilderness. Alone and away from the river in Arkansas, he found the landscape “almost destitute of every thing which is agreeable to human nature; nothing yet appears but one vast trackless wilderness of trees, a dead solemnity, where the human voice is never heard to echo, where not even ruins of the humblest kind recall its history to mind, or prove the past dominion of man.” In August 1819, at his lowest, beleaguered by an excruciating headache and violent heat, he “imprudently” drank some tepid water and became desperately ill. Fever, diarrhea, and the “unremitting gloom” of sunless skies were compounded into “miseries of sickness, delirium, and despondence” until his mind “became so unaccountably affected with horror and distraction that, for a time, it was impossible to proceed to any convenient place of encampment.” Soon after, a blind Osage chief and a squadron of “impertinent squaws” (compared by Nuttall to Macbeth’s witches) stole his canoe, tried to steal his horse, and then, in a wild thunderstorm, chased him through the darkness, into quicksand, and across a frigid river—“the most gloomy and disagreeable situation I ever experienced in my life.” (Nuttall 1821)

The Journal includes Nuttall’s impressions of Indian tribes, for he hoped to contribute to both natural history and the history of his adopted country, especially of “the unfortunate aborigines, who are so rapidly dwindling to oblivion.” Along the Ohio he found Shawnees “ever flying from the hateful circles of civilized society,” as well as white settlers “all searching for some better country” but “destitute of the means or inclination of obtaining an honest livelihood.” In Arkansas Territory he was repelled by the sight of Osage chiefs begging tobacco and degraded by “intercourse with the civilized world” to acquire “merely artificial wants,” yet he was impressed by the Quapaws, who, without civilized restraints, had not abandoned “the obligation to decorum and the essential ties of society.” The Cherokees, granted land in the Territory, might become, Nuttall believed, a “powerful and independent nation” if they embraced the “habits and industry of the Anglo-Americans.” Elsewhere he’s philosophical about human nature and more skeptical about civilization’s supposed benefits: “Yet so nicely balanced, in every situation, is the proportion of good and evil allotted to humanity, that one stage of society has but little advantage over another.” Three appendices to the Journal, with linguistic notes on Southwestern tribes, would, Nuttall hoped, rectify the dismissal of Indian languages as “barbaric” and “create a new era in the history of primitive language.” (Nuttall 1821)

Nuttall’s books brought him to the attention of Harvard, which hired him in 1822 as a natural history lecturer and curator of its botanical garden. Without formal academic training, Nuttall was never made a professor, but over time, Harvard doubled his salary, allowed him to take botanizing leaves of absence, and awarded him an honorary masters of arts degree. In 1830 he was also elected the first president of the Boston Society for Natural History. Nuttall was a popular teacher, guiding students on rambles through nearby woodlands, though his reputation for oddity persisted. Donald Culross Peattie described him as “a shy, eccentric bachelor, shabbily dressed and parsimonious from necessity . . . During his curatorship of the botanical garden at Harvard it was his fancy to cut in his house all sorts of secret doors, which had for their purpose only his privacy; as a result, a man might enter Nuttall’s study and find there nothing but innumerable cages of birds, with which this elvish little man continually experimented.” (Peattie 1935)

Nuttall grew increasingly restive during his eleven years at Harvard. In that era, “Harvard was a veritable desert for a biologist” (Hanley 1977), and Nuttall later described his Cambridge years as vegetating with the vegetation. But his experiments with caged birds, whatever their purpose, were more than idle whimsy. At the close of his Harvard career, he brought forth A Manual of the Ornithology of the United States and Canada in two volumes, The Land Birds (1832) and The Water Birds (1834). Small, inexpensive, and filled with clear woodcut drawings, the manual became a popular guide that, as Christopher Leahy has remarked, “might qualify as the first field guide to North American birds.” (Leahy 2004) Ralph Waldo Emerson praised the book, and Audubon carried an annotated copy. In fact, Audubon visited Nuttall in Cambridge with the hope that the author might show him his first Olive-sided Flycatcher. Nuttall did find him his bird, though it took some searching for a rifle to borrow before Nuttall could shoot it and Audubon could use it as the model for his painting of a “Cooper’s Flycatcher.”

Illustration accompanying Screech Owl entry in original edition of Nuttall’s Manual.

Nuttall’s Manual brings us back to the time when American bird people delighted at finding Party-colored Warblers (Northern Parulas, also known as Finch-Creepers), Hair-Birds (Chipping Sparrows), High- holders (Northern Flickers), Hang-nests (or Firebirds or Golden Robins—Baltimore Orioles), Titlarks (American Pipits), Rain Crows (Yellow-billed Cuckoos), and Cat Owls (Great Horned). If Nuttall found wilderness more appalling than awe- inspiring, birds enraptured him. “They play around us like fairy spirits,” he rhapsodizes in the introduction, “elude approach in an element which defies our pursuit, soar out of sight in the yielding sky, journey over our heads in marshaled ranks, dark like meteors in the sunshine of summer, or, seeking the solitary recesses of the forest and the waters, they glide before us like beings of fancy. They diversify the still landscape with the most lively motion and beautiful association. . . Their lives are spent in boundless action; and Nature, with an omniscient benevolence, has assisted and formed them for this wonderful display of perpetual life and vigor, in an element almost their own.” (Chamberlain 1891)

Unburdened by the modern scientist’s skittishness toward anthropomorphism, Nuttall, like other naturalists of his century, freely praises or disapproves of the habits of particular species. He commends birds generally for their conspicuous “conjugal fidelity and parental affection,” though he grants that fidelity usually “expires with the season.” Parasitical species, he concedes, are guilty of treachery—“the whole tribe of Cuckoos are in disgrace for the unnatural conduct of the European and some other foreign species”—yet he reminds us that avian parasitism is relatively rare. With other early Americans, Nuttall celebrated the skill, fearlessness, and ferocity of Eastern Kingbirds. Other favorites include the American Crow and Northern Mockingbird, which, despite character flaws—the crow’s thievishness, the mocker’s capriciousness— bring intelligence to mischief and can be easily domesticated and “reconciled to the usurping fancy of man.” He admires the crow’s skill in opening doors by alighting on the latches, and its ability to recognize its “master” even after a long absence. Of the mockingbird, he says: “Nothing escapes his discerning and intelligent eye or faithful ear. He whistles perhaps for the dog, who, deceived, runs to meet his master; the cries of a chicken in distress bring out the clucking mother to the protection of her brood.” (Chamberlain 1891)

Photo of stamp of Pacific Dogwood (named for Nuttall, Cornus nuttallii) from the U.S. stamp gallery.

Nuttall isn’t shy about making claims for bird intelligence: “We cannot deny to the feathered creation a share of that kind of rational intelligence exhibited by some of our sagacious quadrupeds, —an incipient knowledge of cause and effect far removed from the unimprovable and unchangeable destinies of instinct.” Though he grants that it is hard to distinguish between “innate propensity” and “the dawnings of reason” in nest-building, he views the “consummate ingenuity of ornithal architecture,” along with adaptability in choosing nesting materials and sites, as proof of birds’ capacity for “education.” And migratory birds, he believes, exhibit knowledge of the qualities of air far beyond any human conception. Nuttall especially finds signs of intelligence in birds’ adaptations to human proximity. Eagles, crows, and blackbirds, knowing “the powerful weapons and wiles of civilized man,” demonstrate “traits of shrewdness and caution which would seem to arise from reflection and prudence,” while other intelligent birds “soon learn to seek out the company of their friends or protectors of the human species,” the Brown Thrush (Brown Thrasher) even feeling “real and affectionate attachment” to people (Chamberlain 1891).

Nuttall likes to tell stories of remarkable birds, such as a canary, taught to play dead as part of a London stage show, that “suffered itself to be shot at, and falling down, as if dead, was put into a little wheelbarrow and conveyed away by one of its comrades.” He anticipates modern ornithological research in his fascination with a celebrated parrot that could answer questions and whistle a repertoire of tunes— even correcting minor errors in its singing—as it continued to “beat time with all the appearance of science.” (Chamberlain 1891) Scientists at Harvard now study Snowflake, a head-bopping, time-keeping Eleonora Cockatoo that can synchronize its body movements—dance—to human music, especially Backstreet Boys songs. The link between the ability to mimic sounds and the capacity for “beat induction” may offer clues about both the development of avian brain systems for learning song, and the evolution of human language.

Nuttall’s guide was precise and accurate enough for many readers to assume its author must have been a trained ornithologist, but it contained some errors and questionable species, and it eventually became dated because of changes in ornithological classification and nomenclature, as well as discovery of new species. In 1891 Montague Chamberlain, a co-founder of the American Ornithological Union, edited and annotated a revised edition, A Popular Handbook of the Ornithology of the United States and Canada, based on Nuttall’s Manual. Chamberlain prepared the book by “taking Nuttall’s biographies and inserting brief notes relating the results of recent determinations in distribution and habits” (Chamberlain 1891). He omitted species that occur only west of the Mississippi valley. Chamberlain notes that some of Nuttall’s birds were later reclassified, like the American Redstart, formerly considered a flycatcher, and he points out cases in which Nuttall, sometimes passing along the errors of Alexander Wilson or Audubon, gave species status to birds—Washington Eagle, Winter Hawk, and Hemlock’s Warbler—that were immature versions of the Bald Eagle, Red-shouldered Hawk, and Blackburnian Warbler. Chamberlain also explains the relegation of some species to the AOU’s “hypothetical” list, including Audubon’s Small-headed Flycatcher, which Nuttall claimed to have seen but which had never been found by later observers; the mysterious Carbonated Warbler, included by Nuttall on Audubon’s authority but never seen after Audubon allegedly killed two specimens in Kentucky; Cuvier’s Kinglet, included by Nuttall because of a single bird shot by Audubon in Pennsylvania; and Townsend’s Bunting, perhaps a Dickcissel with a rare color mutation, included by Nuttall because of a specimen shot by John Kirk Townsend in Pennsylvania.

Chamberlain generally lets Nuttall speak for himself in the revised work, though he can’t resist poking Nuttall for his lukewarm appreciation of Winter Wren song, and he can be opinionated in his own right, as when he badmouths falcons as nothing more than “handsome stalwart ruffians . . . They are neither the most intelligent nor most enterprising of birds, not the bravest.” At a time when some of Nuttall’s birds were near extinction, Chamberlain bemoans the coming loss of the Carolina Parakeet, “not quite exterminated yet” but slaughtered first by farmers and fruit-growers and later for the sake of “woman’s vanity and man’s greed. From the combined attack of such foes the remnant has but slight chance of escape.” His prediction echoes Nuttall’s outraged plea in the original Manual: “Public economy and utility, then, no less than humanity, plead for the protection of the feathered race; and the wanton destruction of birds, so useful, beautiful, and amusing, if not treated as such by law, ought to be considered a crime by every moral, feeling, and reflecting mind” (Chamberlain 1891).

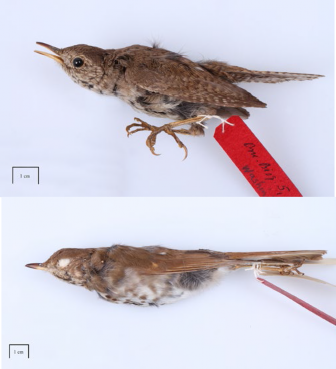

After publication of the second volume, Nuttall and young ornithologist John Kirk Townsend joined an expedition led by Boston inventor Nathaniel Wyeth, which started in St. Louis in 1834 and crossed the Rockies to the Pacific Ocean. Exploring lands never studied by naturalists, Nuttall and Townsend marveled at the variety and abundance of wildlife in the grasslands and mountains, along the Snake River, and to the mouth of the Columbia. Nuttall discovered a new nightjar, the Common Poorwill, in the Wind River Range, and Townsend collected a number of new birds, including Mountain Plover, Vaux’s Swift, Sage Thrasher, Black-throated Gray Warbler, and Chestnut-collared Longspur. In his narrative of the journey, Townsend admired Nuttall’s persistence in finding and preserving specimens, though one night Townsend returned to camp to find Nuttall and their captain picking at the bones of a cooked owl that Townsend had killed and intended to preserve. Nuttall and Townsend sent nearly a hundred bird skins to the Academy of Science and their friend Audubon, who used them as models for Birds of America. “Cheap as Dirt too,” Audubon wrote John Bachman after he’d purchased the specimens. “Only one hundred and Eighty-Four Dollars for the whole of these, and hang me if you do not echo my saying so when you see them!! Such beauties! Such rarities! Such Novelties! Ah my Worthy Friend how we will laugh and talk over them!” (Hanley 1977) Several of these specimens now reside at the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology, including a Hermit Thrush subspecies (Catharus guttatus nanus) and a House Wren subspecies (Troglodytes aedon parkmannii).

Troglodytes aedon parkmannii (above) and Catharus guttatus nanus (below). These specimens were collected by Nuttall and Townsend. Credit: Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University. Photos ©President and Fellows of Harvard College.

From Fort Vancouver, Nuttall and Townsend traveled to the Sandwich Islands, now Hawaii, but their time in the islands was “recreational and not recorded” (Gibbons and Strom 1988). After their return to Oregon, Nuttall ventured on to the virgin scientific territory of California, where, in addition to new plants, he found Yellow-billed Magpies, Tricolored Blackbirds, and Black Phoebes. Townsend died at age 41 in 1851 from exposure to the arsenic he had used in his taxidermy, ultimately sacrificing his life for his science.

Drawing of Nuttall’s Woodpecker by Donald Malick, published in National Geographic.

In 1836, Richard Henry Dana, a young Harvard graduate who’d shipped out as a sailor, was astonished to find his old professor barefoot and gathering stones and shells on a San Diego beach. “I knew him at once,” Dana wrote, “though I should not have been more surprised to have seen the Old South steeple shoot up from the hide house.” Nuttall, transporting boxes and barrels of plant specimens and shells, became the only passenger on Dana’s ship The Alert, which was carrying animal hides from Monterey to Boston. The other crewmen, “puzzled to know what to make of him,” nicknamed Nuttall “Old Curious” because of his “zeal for curiosities.” Nuttall usually stayed below during a month of treacherous gales and icebergs around Cape Horn, but east of Tierra del Fuego, he “came out like a butterfly” on deck and was “hopping around as bright as a bird.” At Staten Land, now Isla de Los Estados, Nuttall begged the captain to let him ashore to “examine a spot which probably no human being had ever set foot upon” (Dana 1937), but the ship sailed on.

Nuttall was fifty when he returned from his two-year trip to the West. It proved to be his last collecting expedition. From 1836 to 1841, he worked in Philadelphia at the Academy of Natural Sciences, contributed to Asa Gray and John Torrey’s Flora of North America, and gave popular lectures on natural history. In 1841 an uncle left him a fortune and estate in Lancashire, but stipulated that Nuttall live there at least nine months each year. “He accepted the bequest,” says Peattie, “because he wished to give the money to a sister; but it meant, as he put it, exile in his native land” (Peattie 1935). Nuttall returned to America just once, on a six-month visit to Philadelphia in the winter of 1847–48. In England he wrote: “I prefer the wilds of America a thousand times” (Kastner 1977). As botany and ornithology became formalized professions, self-taught amateurs like Nuttall were giving way to often stay-at-home academic specialists, but he prided himself that he’d done his work “not in the closet but in the field” (Kastner 1977).

With William Bartram, Wilson, and Audubon, Thomas Nuttall belonged to the tribe of scientifically-minded, stop-at-nothing naturalist pioneers who—often on foot, often at risk, and often near broke—covered untold miles to find, study, order, and represent the birds, plants, and other wildlife of the New World. Nuttall’s biographer, Jeannette Graustein, claims that his “field knowledge of the natural history of temperate America was unequalled” (Kastner 1977). His legacy lives on through the names of three Western bird species he discovered—Nuttall’s Woodpecker (Picoides nuttallii), Yellow-billed Magpie (Pica nuttalli), and Common Poorwill (Phalaenoptilus nuttallii)—and the scientific names of a long list of land and marine plants, including Pacific dogwood (Cornus nuttallii), the catclaw briar (Mimosa nuttallii), and Nuttall’s violet (Viola nuttallii).

He was further commemorated through the naming of the Nuttall Ornithological Club, founded in Cambridge in 1873 as America’s first ornithological society and publisher of the nation’s first bird journal. Its distinguished members have included William Brewster, Theodore Roosevelt, Ludlow Griscom, Roger Tory Peterson, Ernst Mayr, and many other influential figures in the history of American ornithology and conservation. The club continues to publish scientific research, building on its namesake’s groundwork, and meets monthly for lectures at the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology.

References

- Chamberlain, Montague, ed. 1891. A Popular Handbook of the Ornithology of the United States and Canada, based on Nuttall’s Manual. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company.

- Cooper, James Fenimore. 1985. The Leatherstocking Tales, Volume I. New York. The Library of America.

- Dana, Richard Henry. 1937. Two Years before the Mast. New York: P. F. Collier and Son. Gibbons, Felton and Deborah Strom. 1988. Neighbors to the Birds: A History of Birdwatching in America. New York: W. W. Norton.

- Hanley, Wayne. 1977. Natural History in America from Mark Catesby to Rachel Carson. New York: Quadrangle Press.

- Kastner, Joseph. 1977. A Species of Eternity. New York: Knopf.

- Leahy, Christopher. 2004. The Birdwatcher’s Companion to North American Birdlife. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Nuttall, Thomas. 1821. A Journal of Travels into the Arkansas Territory, During the Year 1819; With Occasional Observations of the Manners of the Aborigines. Philadelphia: T. H. Palmer. [1966 Readex Microprint]

- Peattie, Donald Culross. 1935. An Almanac for Moderns. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons.

- Southwest Colorado Wildflowers. 2015. Biographies of Naturalists: Thomas Nuttall.

John Nelson, of Gloucester, contributes regularly to Bird Observer and has published essays about birds in The Antioch Review, The Gettysburg Review, Harvard Magazine, The Harvard Review, The Missouri Review, and The New England Review as well as Birding, Birdwatching, Birdwatcher’s Digest, and the British journal Essex Birding. His essay on birds and dance, “Brolga the Dancing Crane Girl,” was awarded the Carter Prize for the best non-fiction work published in Shenandoah during the 2011-2012 season. He is a director of the Essex County Ornithological Club, a trip leader for the annual Cape Ann Winter Birding Weekend, and chairs the Brookline Bird Club’s Conservation and Education Committee.