Paul Baicich

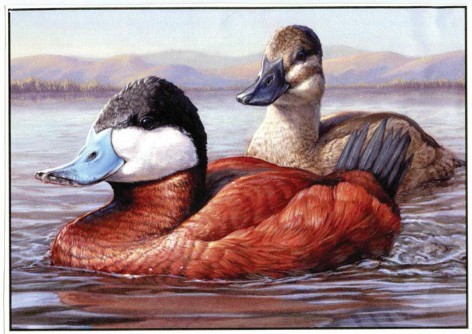

Last September, this artwork, a pair of stunning Ruddy Ducks, was chosen to appear on the 2015-2016 Migratory Bird Hunting and Conservation Stamp. The artist is Jennifer Miller, of Olean, New York. For more information, you may visit the artist's website.

Last year, 2014, marked the 80th anniversary of what today is officially called the Migratory Bird Hunting and Conservation Stamp. Most folks know it as the “Duck Stamp.”

Created in 1934, after a decade of contentious debate, the stamp has been responsible for collecting almost $1 billion in revenue and securing about 6 million acres of wetlands, bottomlands, and grasslands for the National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) system.

Yes, the stamp is required to hunt waterfowl, but it is so much more.

How the Stamp Works

The funds collected each year through stamp sales are deposited into the Migratory Bird Conservation Fund (MBCF). This is the same fund where some import dutiesvon arms and ammunition are also deposited. At least twice a year, the Migratory Bird Conservation Commission meets in Washington DC to determine how these MBCF funds are to be invested in the National Wildlife Refuge System.

At a time when reliable conservation funding for habitat protection is increasingly hard to come by, revenue from the Duck Stamp remains a dependable source, and the MBCF continues to be a highly efficient vehicle for bird-oriented land conservation. It’s something we can all count on, and by law—at least since 1958—the dollars collected cannot be diverted to other purposes.

Today, parts of 252 National Wildlife Refuges accounting for 2.37 million acres and over 200 Waterfowl Production Areas with more than 3.0 million acres owe their existence to the stamp-derived investments made through the MBCF. Starting with the 2015–2016 stamp, which will be available nationwide on July 1, 2015, the price of a stamp will increase from $15 to $25, which should generate an estimated $40 million per year for the MBCF and land acquisition.

Stamp dollars do not simply benefit waterfowl, of course. This funding secures vital breeding, stopover, and wintering habitats for scores of other bird species, including shorebirds, long-legged waders, rails, gulls, terns, raptors, and wetland and grassland songbirds, all highly dependent on habitat derived from stamp purchases. Furthermore, an estimated one-third of this country's officially endangered and threatened species find food or shelter on refuges established through the use of stamp funds.

In New England, one can point to many popular birding locations as places where Duck Stamp and MBCF dollars have been critical to land acquisition (Baicich 2004, Stevens 2007, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service 2014). In Massachusetts, Duck Stamp and MBCF dollars accounted for over 75% of the total acquired habitat for Great Meadows NWR, and slightly above 97% for the Monomoy and Parker River NWRs. Other New England NWRs and their corresponding percentages include Missisquoi in Vermont at 87.5%, Moosehorn in Maine at 67.4%, and Umbagog in both New Hampshire and Maine at a combined 45%. Even the unique Silvio O. Conte National Fish and Wildlife Refuge along the Connecticut River Valley through four New England states — Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Vermont—can attribute chunks of its existence to the wise investment of Duck Stamp and MBCF dollars. In Massachusetts, it is 29%; in New Hampshire, it is 35%; and in Vermont, it is 64%.

To help complete the positive picture, a current and valid stamp is a free pass to any refuge that charges an entry fee, and one stamp is good for a vehicle full of people. For NWRs across the country that charge admission, this benefit is a real bargain. Locally, it applies to Parker River NWR and soon to Great Meadows. How about Bombay Hook NWR in Delaware? Santa Anna NWR in Texas? Bosque del Apache in New Mexico? Merritt Island and J. N. Ding Darling NWRs in Florida? Sacramento NWR in California? Forsythe NWR in New Jersey? Get into the refuge or drive the auto tour route in all of them for free!

It’s Not Perfect

But all isn’t perfect.

For starters, the stamp program is under-appreciated and not enough stamps are being sold, especially considering the current United States population and urgent bird conservation needs. Sales of the 1971–1972 stamp topped 2.4 million at a time when the United States population was only two-thirds of what it is today. Now, however, sales have dropped to about 1.4–1.6 million per year. The stamp certainly needs wider appreciation to generate more sales and deliver more habitat conservation.

This sign is at the Forsythe NWR (often known by its old name, Brigantine) in New Jersey. Over 84 percent of the refuge was acquired through Duck Stamp and MBCF dollars. Here is a case where waterfowl hunters may have paid most of the cost of acquisition, but everyone who uses the refuge, including birders, benefits. (Photo courtesy of the author).

Today, the Migratory Bird Conservation Commission is giving special emphasis to saving grassland habitat, especially the remaining 10,000-year-old native prairie that is disappearing under the plow and being ripped up through oil and gas extraction in the Northern Great Plains. Special emphasis, yes; enough Duck Stamp and MBCF funding, no. And land costs continue to run ahead of the ability to collect stamp dollars. It is a race to save this precious habitat.

There is also a perception problem, one that suggests that the stamp is only for waterfowl hunters. Some of this misperception is a self-inflicted wound. "Duck Stamp" rolls off the tongue easily and has become standard, but “Migratory Bird Stamp” or the tongue-tying “Migratory Bird Hunting and Conservation Stamp” are not often heard. The official name of the stamp changed from the "Migratory Bird Hunting Stamp" to the "Migratory Bird Hunting and Conservation Stamp" in 1977 to better reflect the full impact of the program and to encourage non-hunters, e.g., nature photographers and birders, to buy the stamp. Until recently, however, little was done to make that appeal a reality.

In addition, there is a promising but troubled youth component. The popular Junior Duck Stamp Program has mobilized tens of thousands of students every year since the early 1990s to combine science standards with visual arts. This national initiative has had great success, but is currently suffering from the twin assaults of narrowing local school curricula and shrinking federal dollars to sustain the program. If anything, the Junior Duck Stamp Program needs strengthening to continually encourage the next generation of wildlife conservationists.

We could all benefit from detailed tracking of exactly who buys the stamps. How many are waterfowl hunters? Non-waterfowl hunters? Birders? Wildlife photographers? Collectors? It would be good to know where the stamps are sold and, especially, who buys them. The gross sales numbers on a yearly and state basis are available, but the particular numbers, crucial in measuring and producing an effective marketing effort, are absent.

Finally, the most recent increase in the stamp price may hinder broader sales.

Another Way to Look At It

Last fall, Scott Yaich, Director of Conservation Operations at Ducks Unlimited, and I tried our best to answer an essential question: “How much does just one stamp secure in the way of wetland and grassland habitat?” We attempted to pursue a reasonable answer for any individual who bought a Migratory Bird Hunting and Conservation Stamp in the last year.

Looking at about $53 million that came into the Migratory Bird Conservation Fund in 2013 from stamp sales and import duties, the combined fee title and easement acres of wetland, bottomland, and grassland habitats secured during the year was 60,000 acres. With about $883 per acre of habitat secured, we arrived at 1.66% of an acre, or 725 square feet.

That was impressive, an area slightly under 27 feet x 27 feet, or almost the combined floor space of an average bedroom, kitchen, and dining room in a new home in the United States in 2013. The comparison was appropriate, producing a “bedroom,” “kitchen,” and “dining room” for birds and other wildlife. Moreover, to be able to stand somewhere on some federal refuge land and think that “my stamp” secured a block that’s about 725 square feet, should be enough to make anyone feel proud. See the accompanying sidebar for a downloadable certificate related to this calculation.

Where Birders Come In

The price of a Migratory Bird Stamp reached $15 back in 1991. With the need to keep up with land acquisition and easement costs, especially since valuable habitat prices have tripled over the last three decades, it was important for the price of the stamp to rise. Indeed, what you may have bought for $15 in 1991 today costs about $25.75. It is no accident then that the stamp price is finally rising from $15 to $25, starting with the new 2015–16 stamp.

But as indicated before, this price increase also brings up a problem. Going back to the same well again and again, in this case to a dwindling number of waterfowl hunters, is not a long-range solution to the habitat acquisition problem. More stamp buyers have to be found. Moreover, asking those who are not required to buy a stamp—say, bird watchers or wildlife photographers—to voluntarily buy a $25 stamp is not simple.

While not an easy sell, the price of the next stamp is about equal to the price of a decent large pizza and will likely be one of your smaller birding expenses. More importantly, it is still the easiest thing anyone can do to protect crucial wetland and grassland habitat.

Duck Stamps are easy to buy. They are available at most large U.S. Post Offices or at staffed NWR Visitor Centers. If you buy your stamp online at store.usps.com, you can save a trip and have it mailed to you for a modest $1.30 fee. The availability is there.

Fortunately, there have been a number of birder-oriented organizations that have stepped up to the challenge of selling stamps, either individually or in special plastic display holders. These organizations include the Georgia Ornithological Society, the Wisconsin Society for Ornithology, the Black Swamp Bird Observatory, the Klamath Bird Observatory, and the American Birding Association. You can pick one up at Massachusetts Audubon’s Joppa Flats Education Center.

For birders, however, the important thing is not just to buy the stamp, but also to display the stamp, to show it off. See the sidebar for ideas.

Last fall, Mike Burke, a birder and naturalist who writes regularly for the Maryland-area Bay Journal, wrote: “Today, birders are the pre-eminent sportsmen of our age and our numbers continue to grow.” He focused on the Duck Stamp, and continued, "with an influx of dedicated funds, programs to conserve and restore habitat can garner strong support among birders and benefit countless avian species" (Burke 2014.)

For all these good reasons, buying the “Migratory Bird Hunting and Conservation Stamp,” or the “Duck Stamp,” or the “Migratory Bird Stamp”—whatever you wish to call it—is the way to go.

Sources

Paul J. Baicich lives in Maryland and is co-author of Nests, Eggs, and Nestlings of North American Birds (1997, with Colin Harrison) and, most recently, co-author of Feeding Wild Birds in America (2015, with Margaret Barker and Carrol Henderson). Paul is an officer in the Friends of the Migratory Bird/Duck Stamp.