Peter Brown

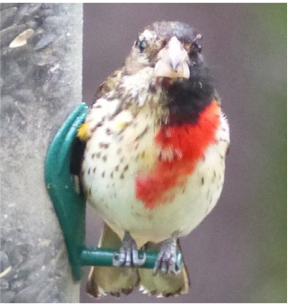

Bilateral gynandromorph Rose-breasted Grosbeak at author’s feeder. (All photographs by the author)

On the morning of June 15, 2015, I was looking out at my bird feeder from my kitchen when I spotted what I thought was a female Rose-breasted Grosbeak (Pheucticus ludovicianus). The heavily wooded area in which I live in Newbury, Massachusetts is less than a couple of miles from the Merrimack River and Plum Island, and has an abundance of wood warblers and passerines. Rose-breasted Grosbeaks have been frequent visitors to my feeder during the five years I’ve lived in this house, so this sighting did not immediately produce much of a stir. My feeders sit about 15–18 feet from my kitchen windows, so I have a front-row seat as I drink my coffee and watch for visitors each morning.

When I looked up a couple minutes later I thought a male had joined the female as I saw the distinctive red spot on the white chest and the deep black head. Yet, there was something wrong with this bird’s plumage development. My first reaction was that the bird was an underdeveloped fledgling or juvenile because the male coloration didn’t run completely across the bird’s chest. In fact, it looked as if the male plumage came to an abrupt stop right in the middle of the bird.

Bilateral gynandromorph Rose-breasted Grosbeak at author’s feeder.

I always keep a camera handy in case something interesting shows up at the feeder, so I quickly reached for it and began firing away hoping I was getting focused shots in case the bird flew away. The bird cooperated and I was able to take about 5–10 pictures before it left the feeder. I hadn’t looked at the bird through binoculars so my photos were the first close-up views I had. While I waited to see if it would return, I quickly viewed what photos I had captured and was stunned to see that the bird was showing both male and female plumage. In one photo shot head on, the right side of the bird had the female characteristics of yellow underwing color, brownish overall color, and white eye-stripe, whereas the left side of the bird had the solid black head, white chest feathers, and rose red spot of a male. These two plumages seemingly ran right down the two halves of the bird, from the tip of the beak to the end of the tail. Depending on which side was facing out this bird was half male, half female by plumage.

I waited and was rewarded with a couple more feeder visits and got some photos from slightly different angles. The bird was not unusual in any aspect other than plumage. It’s feeding habits, size, and general behavior were not different from what you’d expect. It just looked weird.

Bilateral gynandromorph Rose-breasted Grosbeak at author’s feeder.

As I was to learn later that morning, what I was looking at was a bilateral gynandromorph. I shared my photos with Wayne Petersen at Massachusetts Audubon and with Bill Gette at Joppa Flats, who confirmed the rare nature of my sighting. Bill came over to my house the next morning and was able to see the bird in person and capture a couple of photos. As it turned out, Bill was the last person to see the bird.

What makes a bird a bilateral gynandromorph? The sex chromosomes of birds are called Z and W, and females are ZW but males are ZZ (note how birds differ from mammals in which females are XX and males are XY). Bilateral gynandromorphic birds, such as the grosbeak I observed, have mostly female ZW cells on one side of the body and mostly male ZZ cells on the other (Zhao et al. 2010). These rare birds are thought to arise from an abnormal egg cell that has two nuclei—one with a W chromosome and one with a Z chromosome. If each of these nuclei is fertilized with a sperm carrying a Z chromosome, then, after the egg divides, the embryo will consist of one female ZW cell and one male ZZ cell. As these first two cells and their descendants continue to multiply, the newly produced female ZW and male ZZ cells may stay on opposite sides of the embryo with little mixing, resulting in the full-grown gynandromorphic bird—one side male and the other side female by plumage.

Getting back to the bird, so what happened next?

As I said, I have had one or two resident pairs of Rose-breasted Grosbeaks each spring that are also regular visitors to the feeder. One pair showed up about an hour after the gynandromorph and began to take control of the feeder perches, thus letting the solitary Rose-breasted Grosbeak know that it was trespassing. Working in tandem for most of the morning, this pair discouraged the gynandromorph from returning to feed. I watched for another hour but the bird did not return that day.

The bird may have visited for only a day or two, but his/her reputation lived on past departure. As part of their weekly bird events update, the people at the Joppa Flats Massachusetts Audubon center shared my photos with the Newburyport Daily News.

I got a call and gave a short interview on my observations. A photo of the bird and a short story made it to the front page of the newspaper. About two weeks later, I got a phone call from an editor in the newsroom at WBZ–TV who also thought the photos and story were newsworthy. I sent them photos and hope the rarity was viewed by more people. It will be interesting to see if the bird returns next spring. image

References

- Hendrickson, D. 2015. Rare ‘gynandomorph’ bird found in area. Daily News of Newburyport. Available online.

- Zhao D., D. McBride, S. Nandi, H. A. McQueen, M. J. McGrew, P. M Hocking, P. D. Lewis, H. M. Sang, and M. Clinton. 2010. Somatic sex identity is cell autonomous in the chicken. Nature. 46: 237–242.

Peter Brown is a birder from Newbury, Massachusetts.