Kate E. Iaquinto

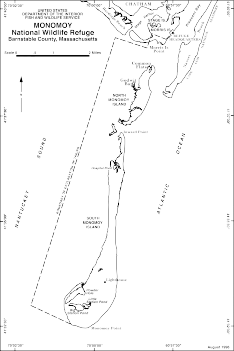

Figures 1 & 2. (Left) Map of the original refuge boundary and landform when Monomoy NWR was established in 1944. Figure credit: USFWS 1944, Division of Realty.

(Right) Map of the islands after the Blizzard of 1978. Figure credit: USFWS 1988. Environmental Assessment—Master Plan: Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge. Chatham, Massachusetts. 186 pp. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Hadley, Massachusetts. [AR, lC, 307-490] U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Region 5, Newton Corner, Massachusetts.

Chatham, Massachusetts, located on the elbow of Cape Cod, is the quintessential coastal New England town and summer destination for many tourists. More recently, Chatham has been in the news for its increasing gray seal population and the great white sharks that have followed. These are amazing wildlife resources, but what makes Chatham special to birders is the enormous diversity and numbers of avian species that can be seen here.

Chatham is home to an extensive barrier beach system, part of which was established in 1944 by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) as Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge (refuge or NWR). These islands are immensely important for nesting and migratory shorebirds and seabirds. In 2016 alone, the refuge and adjacent South Beach hosted 67 pairs of Piping Plovers (Charadrius melodus), 10,505 pairs of Common Terns (Sterna hirundo), 14 pairs of Roseate Terns (Sterna dougallii), over 700 pairs of Least Terns (Sternula antillarum), 19 pairs of American Oystercatchers (Haematopus palliatus), and saw thousands of migrant shorebirds and staging terns. Monomoy NWR is also a diverse nesting area for waterfowl such as American Black Duck (Anas rubripes), wading birds such as Black-crowned Night-Heron (Nycticorax nycticorax) and Great Egret (Ardea alba), and landbirds including Savannah Sparrow (Passerculus sandwichensis) and Saltmarsh Sparrow (Ammodramus caudacutus). The dynamic nature of the Monomoy barrier beach system is what makes it a unique and important place to protect for all of the species that depend on it.

To me, the feeling of Monomoy is always the same regardless of its physical form or a particular map. It is a beautiful barrier beach that has for many hundreds of years stretched miles off the shore of Chatham. Whether it was a peninsula or a chain of islands, whether it was connected or disconnected, whether it was inhabited or deserted, the place remains the same: a stretch of beautiful beach—largely unaltered by humans—that is essential wildlife habitat, especially for birds.

While looking at our refuge map, a visitor recently asked me if the map showed “what it looks like out there right now.” “That’s a tricky question!” I said. The map was a 2015 aerial, but since the area is constantly changing, aerial imagery is immediately outdated. We see measurable changes in the shoals and channels on a daily basis; this place does not remain the same for more than one tide cycle. Each day the tides ebb and flow and so do the beaches of Monomoy and the inlets that enable boat access to the southern end of South Beach and the northern end of South Monomoy Island. One day, one route is perfectly acceptable to pass through at mid tide; the next week, it is no longer passable. This makes it a constant challenge and keeps us on our feet. It also discourages many boaters except those who are the most experienced or have a stake in getting out there, e.g., the refuge’s and Mass Audubon’s Coastal Waterbird Program staff, shell fishermen, and the occasional birding group, fin fisherman, or beachgoer.

The dynamic nature of Monomoy is also what makes it so intriguing, especially to the public for many of whom the refuge islands are out of reach. One needs a private boat or permitted tour boat to access the refuge. This is problematic because it prevents the public from easily visiting their national wildlife refuge, and it impedes friends’ groups and volunteers hoping to access the refuge for service projects. But this inaccessibility is part of what makes Monomoy so special; its relative isolation from human populations enhances its value for the wildlife populations we are working to conserve.

I have had the pleasure of working at Monomoy since the summer of 2007. Monomoy is a challenging refuge to work at for many reasons. We are a federally designated Wilderness area, which guides the management applied on the refuge, often meaning that we use more primitive techniques. We have a field camp where our seasonal staff live and work seven days a week from May through July. We manage habitats for four threatened or federally endangered species: Piping Plovers, Roseate Terns, Red Knots (Calidris canutus rufa), and northeastern beach tiger beetles (Cicindela dorsalis dorsalis). We are a Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network site of regional significance, meaning that tens of thousands of shorebirds pass through annually during migration. We have only three permanent staff members and a small army of volunteers and seasonal staff to get all of our work done. But the fact that the island is actually a moving target makes logistics from year to year one of our biggest challenges. When I first started working at the refuge, I was a seasonal technician with big dreams, never suspecting that I would still be at Monomoy in 2016, and better yet as the refuge biologist. I have seen a lot of amazing changes to this dynamic area in what amounts to a split second of geologic time. I’ve also seen great increases in many of our focal species—especially plovers and terns—but let’s start from the beginning.

Geomorphological History: 1944-2006

The area now known as Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge was a peninsula in 1944 (see Figure 1) when the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service established the refuge. Along the east side of the refuge was the Atlantic Ocean, and Nantucket Sound was to the west. The sand that would become South Beach—then the southern extent of Nauset Beach—terminated due east of the Morris Island Refuge property (USFWS 2016). Originally set aside for migratory birds, specifically breeding and migrating waterfowl, the refuge was a popular place for hunting and fishing and was used quite heavily by the public. As long as the refuge property remained joined to Morris Island, cars were able to travel down the beach, providing easy access to the southern extent of the refuge. However, that changed during a spring nor’easter in 1958 when the peninsula separated from the mainland. For a short time, vehicles could still access the refuge via a ferry, but that was short lived as the break became more and more substantial. The majority of the refuge land became an island, isolated from the mainland and preventing easy public access.

In 1970, the United States Congress designated most of the offshore portions of Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge as a wilderness area. Per the Wilderness Act of 1964, this designation ensured that the refuge would be administered for the use and enjoyment of the American people in such manner as will leave it unimpaired for future use as wilderness. This meant that the beach shacks that had been present on the refuge had to be removed and vehicles would no longer be allowed to access the refuge. Allowances in the wilderness designation were made for access to actively used cabins, but this designation truly changed how the public could access the refuge.

In 1978, Monomoy was changed again quite dramatically. The blizzard of 1978 created 20 temporary breaks in Cape Cod’s outer beaches (Milton 2008), including a new break at Monomoy. The refuge island was split into three: North Monomoy Island, South Monomoy Island, and what would become Minimoy Island, which was first only a flood shoal between North and South Monomoy Islands (See Figure 2).

Figure 3. This photograph, taken from South Monomoy Island facing northeast toward South Beach, shows how close the two properties were before they connected during a Thanksgiving Day storm later in 2006. Photo credit: USFWS 2006.

As the offshore portions of the refuge became more distant from the mainland and harder to access due to shoaling around the northern extent of the refuge, fewer and fewer people were using the island for recreation; more space became open and maintained in its natural state for wildlife. The outer beach—Nauset Spit and North Beach, Chatham—crept closer and closer to the refuge until it broke during a coastal storm in 1987. The end of Nauset Spit became an island that rejoined the mainland across from the United States Coast Guard Station, Chatham, in 1992 (Keon and Giese 2015). This beach, newly accessible from the mainland, became known as Chatham’s South Beach.

As South Beach continued to grow southward due to southerly longshore currents in the Atlantic Ocean, it gradually became the home to many pairs of nesting Piping Plovers. South Beach—especially its southern reaches that grew farther and farther from the mainland — was also much longer and less disturbed than other Cape beaches, many of which, including large portions of the National Seashore, allow off-road vehicle access. Mass Audubon, and later its Coastal Waterbird Program (CWP), worked with the Town of Chatham and the Massachusetts Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program (NHESP) to monitor Piping Plovers and Least Terns at the site beginning in 1992, which continues today. During that first year, South Beach hosted 12 pairs of Piping Plovers (Melvin 1992) but peaked around 64 pairs in 2013 (NHESP 2015).

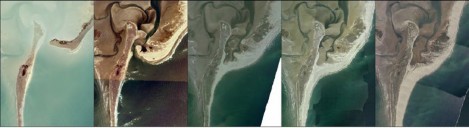

Figure 4. This series of aerial imagery depicts, between 2001 and 2015, the area where the connection of South Beach and South Monomoy Island occurred in 2006. Images were taken by the James W. Sewall Company and were funded by the FWS and the Town of Chatham.

During the years between 1992 and 2006, South Beach continued to migrate south, growing longer and becoming more vegetated. As South Beach grew, more of the refuge islands became protected from ocean waves; sand flats formed along the inside waterway, known as the Southway, between the refuge and South Beach. In a Thanksgiving nor’easter in 2006, South Beach and South Monomoy Island joined, sealing off the southern extent of the Southway and no longer allowing access to the Atlantic Ocean. This event also marked the first time since 1958 that it was possible to walk on dry land from the United States Coast Guard’s Chatham Light to Monomoy Light. (See Figure 3.)

The Connection of Monomoy NWR and South Beach, Chatham: 2006-2013

My first summer at Monomoy NWR was 2007, following the connection of South Beach and South Monomoy Island. Everything had just changed dramatically, but to me it all seemed normal. I was hired as a seasonal biological technician responsible for monitoring Piping Plovers and assisting with other biological projects as needed. My undergraduate training and my experience working for several years with Piping Plovers for the Fish and Wildlife Service in Rhode Island prepared me well for my time at Monomoy. At the time, I had no idea that I would end up working at the refuge for so long! I thought I would be there for the summer, maybe a second season, but I could not have predicted how that first summer would change my life.

The connection of South Beach and South Monomoy Island changed a few things around the refuge immediately; first, Mass Audubon began sharing the field camp at Monomoy with the FWS seasonal staff. Field camp has been established annually on Monomoy NWR since the mid-nineties with the initiation of the Avian Diversity Project. The purpose of our field camp is to provide 24-hour human presence near our Common and Roseate tern colony to prevent establishment of predator species in the area, primarily Herring (Larus argentatus) and Great Black-backed (Larus marinus) gulls. We set up the camp using the model that had been successful in reestablishing nesting islands for seabirds in the Gulf of Maine, led by Dr. Stephen Kress and Project Puffin. Having a field camp on the island also enables plover staff to monitor on a daily basis without worrying about when the next boat ride could be, simplifying the challenges of shoaling and weather that can make the waters around the islands inhospitable. CWP staff stationed at our field camp are able to walk to South Beach daily to monitor Least Terns, American Oystercatchers, and Piping Plovers without requiring boat support. This cooperative relationship between FWS and CWP continues to this day and is truly important to enabling the protection of wildlife on Monomoy’s barrier system.

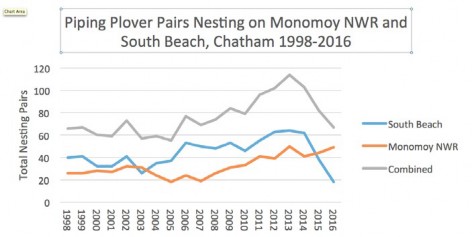

Figure 5. The total count of nesting pairs on Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge and South Beach, Chatham, between 1998 and 2016. Data has been compiled using state census forms from Mass Audubon Coastal Waterbird Program and the US Fish & Wildlife Service at Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge.

Obvious changes in nesting birds occurred with the growth and connection of South Beach to South Monomoy. As South Beach grew it provided more favorable habitat for Piping Plovers. Piping Plovers nest on ocean and bayside beaches above the high tide line but outside of areas that are densely vegetated. The optimal plover nesting habitat is close to foraging areas, which include intertidal ocean beaches, overwash fans, bayside flats, and salt ponds. Wider, more substantial natural barrier beaches attract greater numbers of nesting pairs. Therefore as South Beach grew the numbers of pairs nesting there increased, particularly near the connection where the interior of the barrier system also provided desirable habitat. (See Figure 4.)

Until the actual connection in 2006 South Beach was the area that experienced the most change. However once the connection occurred the longshore drift began depositing sand onto South Monomoy Island as well. Historically the southern tip of South Monomoy Island and a small area on the northeast side known as Plover Beach had been the main nesting sites for Piping Plovers, but after the connection with South Beach the eastern side of the island continued to grow in width and the mudflats between the two sites became great foraging habitat. In 2008, the second summer that the properties were connected, the connection established a wide beach averaging 200–400 meters in width from the vegetation to low tide line that was about two kilometers long. By 2015, the length of that wide beach had doubled to over four kilometers, with much of the area between 300 and 400 meters in width. Due to the beach widening, both the refuge and South Beach saw increases in the number of nesting Least Terns. Most of this wide beach is now on South Monomoy Island and continues to host many pairs of nesting Piping Plovers and Least Terns each year. (See Figure 5.)

Figure 6. Summer of 2011, facing South Beach from the new dune on the east side of the established boundary signs. The image shows the new dune as well as the additional rows of dune and vegetation forming toward the ocean side. Photo credit: USFWS/Aubrey Sirman 2011.

Every year the changes in the connection area continue. In addition to the widening beach and expanding mudflats, the vegetation has changed substantially. In 2007, the first breeding season of the connection, there was no vegetation on the sand connecting South Beach to South Monomoy Island. In fact, it was desert-like. It was a wide expanse of open sand and cobble above the high tide line. By the next year, vegetation began to grow and a dune ridge formed between the Southway and the ocean side. Slowly, as the beach became wider, that new dune ridge became more developed and a second row of dunes formed. Currently, depending on where you are on the connection, there are up to three rows of dunes, as well as a series of hummocks on the outer oceanside beach. (See Figure 6.) These hummocks serve as nesting areas, providing vegetation to shelter Piping Plover and Least Tern chicks. Horned Larks (Eremophila alpestris) use these areas as well.

Each year the connection also experiences varying winter storm damage that changes how dry or wet the areas of the connection are. In 2012, a swale developed between the new dune ridge and oceanside hummocks. This area fills with water from the Southway during storms or astronomical high tides and stays wet between these events, which provides areas of foraging to the large number of nesting plovers surrounding the swale. Many of the broods that hatch chicks on the South Monomoy portion of the connection head to the swale once their chicks are large enough to forage independently. Foraging in the swale allows them to avoid nesting Least Terns. The terns initiate their nests after the plovers do and can be aggressive toward the young plover chicks.

As with the beach portions of the connection, the inside flats of the Southway have become more vegetated since the area closed. While Monomoy NWR has long boasted a growing and expansive salt marsh on North Monomoy Island and smaller areas near Powder Hole and Hospital Pond on South Monomoy Island, South Beach has had only small intermittent patches. When the Southway closed, the interior side of the connection became protected from the currents and waves of the open ocean, creating approximately 20 acres of new salt marsh that continues to grow annually.

This salt marsh and the surrounding flats serve as foraging areas to Piping Plovers and other nesting species and provide immense shellfish resources such as amethyst gem clams (Gemma gemma) that are critical to large flocks of migrant shorebirds, including Black-bellied Plover (Pluvialis squatarola), Red Knot, Dunlin (Calidris alpina), Sanderling (Calidris alba), Ruddy Turnstone (Arenaria interpres), and Short-billed Dowitcher (Limnodromus griseus). The flats inside the connection also provide important staging areas for Common and Roseate terns as well as occasional Black (Chlidonias niger), Sandwich (Thalasseus sandvicensis), Arctic (Sterna paradisaea) and Forster’s (Sterna forsteri) terns.

While these changes in geomorphology benefitted both habitat and our focal species, the connection also presented refuge staff with management challenges. Prior to the connection, the northern tip of South Monomoy Island—the location of the tern colony—experienced occasional overwash during winter storms. This saltwater inundation brought in sand and salt, killing patches of the vegetation and maintaining the early successional dune grassland habitat. Common Terns prefer to nest on the open ground in areas of patchy vegetation that can be used by the chicks to hide from the summer heat. Often, these types of habitats are maintained by occasional winter storm overwash that prevents the herbaceous vegetation from getting too thick and hampers the growth of woody vegetation (Nisbet 2002). As South Beach crept south of the northern tip of the South Monomoy Island tern colony, the area no longer received overwash in winter storms; woody vegetation such as bayberry and rugosa rose quickly colonized. Beach grass also developed a thick layer of duff that prevented terns from nesting within the grass and became more favorable to Laughing Gulls (Leucophaeus atricilla), a competitor of the terns that nest within the South Monomoy Island colony.

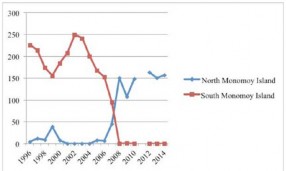

Figure 7. This graph, taken from the 2016 Monomoy Comprehensive Conservation Plan, depicts the number of Black-crowned Night-Herons nesting on the Refuge between 1996 and 2014.

The refuge chose to use fire as a tool to mimic the impacts of saltwater inundation and began performing prescribed burns approximately every two to four years based on the density of South Monomoy’s vegetation and the amount of woody vegetation present. The first burn was in fall 2004 after the terns had left for the winter. It met the objectives of slowing the establishment of woody vegetation, removing the layer of duff within the beach grass, and opening up areas to create a patchier habitat. By burning the 35-acre tern colony site and monitoring the vegetation using a combination of sampling plots and photo plots, the refuge has been able to keep the habitat within the colony in a state that is preferable to terns. The most recent burn in 2015 was a great success; a record number of 10,505 pairs of Common Terns nested in the colony during 2016. The connection of South Beach to South Monomoy Island triggered the necessity for management with fire, but overall it has had the desired outcome and has possibly been more effective than if natural overwash was the only means of clearing vegetation on the north tip.

Another management challenge that we have faced since the connection is the increased number of coyotes and other predator species on the barrier system. Coyotes have been documented on South Monomoy Island annually since 1996 (USFWS 2016). As the tip of South Beach came closer and closer to the island, protecting the Southway from ocean currents and shrinking the amount of water between the mainland and the refuge, the number of coyotes able to swim to the island increased steadily. Once the connection was established, the number of coyotes on the island exploded. Coyotes are common nest predators on Monomoy NWR and South Beach and have been documented depredating eggs and chicks of all of our focal species. Where coyotes seem to have the biggest impact is in the tern colony, with documentation of several different coyotes eating up to 70 tern chicks in one night (unpublished data, Monomoy NWR).

Figure 8. The 2013 break in South Beach at low tide on February 13, 2013. Photo credit: USFWS/Kate Iaquinto 2013.

Coyotes also impacted wading birds and gulls that had previously nested in large numbers on South Monomoy Island. Figure 7 demonstrates how the number of nesting Black-crowned Night-Herons shifts from South Monomoy Island to North Monomoy Island after the connection in 2006. A similar phenomenon was seen with nesting gulls. Between 100 and 200 large gulls nested on South Monomoy Island prior to the connection, but the numbers decreased to less than 100 in 2006 and less than 50 in 2007 (USFWS 2016). By the 2012 census, there were few gulls nesting on South Monomoy Island at all. In both cases, increased numbers of coyotes forced bird species to move their nests to other areas of the refuge.

In addition to increases in coyote numbers, the connection made it possible for opossum to reach South Monomoy Island, though they were documented taking nests only during two years (USFWS 2016). Avian nest predators such as American Crows (Corvus brachyrhynchos) are now a much more common sight on the island than prior to the connection.

The Break in South Beach: 2013-Present

South Beach had been for a long time an important site for local and visiting birders alike. For many years various birding groups, including Mass Audubon and bird clubs from all over the region, could take a ferry out to the southern end of South Beach to bird, especially during the southward migration starting in late July and going into the fall. Refuge staff had the luxury of being able to access the tern colony by boat at almost any tide while protected from the prevailing southwest winds of the summer. As I stated earlier, beginning with the 2006 connection, it was possible to hike between Chatham Light and Monomoy Light, a feat that had not been possible since 1958. This hike, a distance of approximately 8.5 miles one way, was done by several people, many of whom were FWS or CWP staff. I assisted a mother and her nine-year-old son in completing the hike. I gave them maps and suggestions and heard back from them when they had completed it. They had a blast! I really wanted to do the hike, but in 2013 things changed once again, and it was suddenly and surprisingly no longer possible. In February, yet another powerful nor’easter and winter storm created a break in South Beach east of the northern tip of North Monomoy Island.

Figure 9. The 2013 break in South Beach at low tide three weeks later on March 5, 2013. Photo credit: USFWS/Kate Iaquinto 2013.

After the storm passed, I walked down to view the new break. There was quite a bit of sand still in the area where the water had pushed through, and it was possible to walk across the break from the mainland toward South Monomoy. There appeared to be two inlets formed by the overwash. Gradually, these inlets joined into one large gap between the northern and southern portions of South Beach. A former staff member and I marked the inlet with GPS and repeated our efforts three weeks later. The break was changing quickly. (See Figures 8 and 9 for the difference in conditions.) There was a lot of speculation about what exactly would come of this break, and I suppose it is still undecided. Would it seal back up? Would it open completely, allowing boat traffic to access the Atlantic Ocean? The jury is out, the break continues to change, and we are faced with a dramatic new boating situation each spring when we put our refuge boats back into the water. The flood shoals that were formed during the 2013 storm have continued to grow and grow, making navigation through the Southway more and more challenging. The first year of the break, we were able to pass by these shoals during most tides, but slowly over the last three years, our boat access to the southern end of the Southway has become more and more limited. In 2015, ferry services stopped running trips into the Southway for fear that they would get stuck. The refuge was limited to smaller boats and smaller windows of time. In 2016, it was only possible to pass through the shoals within several hours of high tide, the smallest window yet. The Southway is slowly turning into something like a large salt pond.

Figure 10. This aerial imagery depicts the north tip of North Monomoy Island and the portion of South Beach where the 2013 break occurred. Images were taken by the James W. Sewall Company and were funded by the FWS and the Town of Chatham.

Since 2013, the southern half of South Beach has taken a beating. The original growth and development of South Beach between 1992 and 2013 had increased the numbers of nesting Piping Plovers in the area. The sudden shift to the destruction of South Beach after the 2013 break seems to be having a predictable and opposite response for nesting birds. Since the break occurred, South Beach has continued to erode. The southern portion of South Beach is overwashed frequently, so that by 2016 there was very little vegetation left except on the area by the connection. In fact, in 2016, only 24 pairs of Piping Plovers nested on the southern end of South Beach.

The portion south of the break has continued to move westward and southward. Each year the opening between the northern and southern sections of South Beach becomes larger; in 2015 it was almost half a mile wide. Due to the uneven exchange of Atlantic Ocean water and water from the much smaller and shallower Southway, flood shoals have continued to grow on the eastern side of the break, making navigation from the mainland through the Southway impossible at low tide. It is likely possible to walk from the mainland to North Monomoy Island at low tide, but to my knowledge no one has tried. (See Figure 10.)

Unlike the 2006 connection, the 2013 break has caused more trouble and has presented more challenges than benefits. Ocean water rushes into the break at high tide and has caused a severe amount of erosion on North Monomoy Island. Since the 2013 break, the northern half of North Monomoy Island has lost between 20 and 60 meters of upland habitat that protected the salt marsh and provided nesting habitat for American Oystercatchers and the refuge’s colony of Herring and Great Black-backed gulls. The loss of dunes on the north tip of North Monomoy Island has caused the salt marsh to be easily visible from the east side; occasionally it becomes completely flooded during higher tides. Large areas of sand have washed into the salt marsh as well, turning what was high marsh into overwash fans that are flooded at high tide. We do not census nesting Saltmarsh Sparrows in the marsh, but it is almost certain that this change is having an impact on the nesting population on the refuge. The loss of the dunes has contributed to a decline in nesting American Oystercatchers. A statewide gull census will likely be performed in 2017, and I’m sure that we will find the gull numbers to be down since the 2012 census of the colony.

Piping Plovers. Photograph by Sandy Selesky.

The most unfortunate result of the loss of gull nesting habitat in 2016 is that large gulls attempted to nest in the tern nesting area on South Monomoy Island. This was the first year since 2007 that gulls had to be controlled in the tern nesting area to prevent them from establishing a colony. This year we reacted quickly by opening field camp early, harassing gulls non-lethally, and destroying several nests. We assume that this will need to be an annual tradition as less and less habitat becomes available for the gulls on North Monomoy Island. Most gull species are generalists and can persist in many habitats, forage on a wide range of species, and are tolerant of human disturbance. Common Terns, on the other hand, are a state-listed species of special concern and rely on specific undisturbed island habitat and particular forage fish to survive. The refuge must prioritize terns over gulls to meet our conservation goals of maintaining healthy native bird populations.

Although the 2013 break has certainly made things at Monomoy more challenging, it is important to understand that this is all part of a natural cycle. In the time that I’ve been at Monomoy, the geomorphological impacts have caused major changes in nesting species, but ultimately, this barrier system is large enough, diverse enough, and is situated on the earth in such a way that the majority of species that have been present here for decades continue to be there and will continue to be there for the foreseeable future.

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Literature Cited

- Milton, S. 2008. Storm of the Century. Cape Cod Times. February 3, 2008. http://www.capecodtimes.com/article/20080203/news/802030336. Accessed on July 25, 2016.

- Keon, T.L., and G. S. Giese. 2015. Management issues linked to geomorphological changes to the Nauset/Monomoy barrier beach system, Cape Cod, MA. Coastal Sediments 2015. The Proceedings of the Coastal Sediments 2015. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing.

- Melvin, S. M. 1992. Status of Piping Plovers in Massachusetts – 1992 Summary. Westborough, MA: Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife.

- Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program (NHESP). 2015. Summary of the 2013 Massachusetts Piping Plover Census. Westborough, MA: Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife.

- Nisbet, Ian C. 2002. Common Tern (Sterna hirundo), The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology. http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/618 Retrieved July 2016.

- U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. 2016. Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan. March 2016. Hadley, Massachusetts: Northeast Region, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

Kate Iaquinto is a Wildlife Biologist for the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service at Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge. She is currently working toward a Master’s in Environmental Conservation at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Ms. Iaquinto is studying the movements and behaviors of breeding Piping Plovers in Massachusetts and Rhode Island using nanotags.