Tim Spahr

Northern Saw-whet Owl. Photograph by Kristina Servant (CC BY 2.0).

General Information

Northern Saw-whet Owls are common across a large portion of North America. In the breeding season, they range from southeastern Alaska down through the mountainous terrain of the western United States, including southeastern Arizona. There are even resident populations in the mountains of Mexico. They also breed across much of the boreal forest in Canada, and down into the states adjacent to the Great Lakes and into the higher peaks of the Appalachians. In the interior west, they breed commonly in the Rockies. Saw-whet owls preferred breeding habitat is coniferous forests, but they also breed near bogs, forest clearings, and in deciduous forests.

In the nonbreeding season, Northern Saw-whet Owls will often retreat from the coldest climates, working their way south—and lower in elevation—into the mid-southern states such as North Carolina, Tennessee, Missouri, and Kansas. They can be surprisingly common south of the breeding range after a highly successful breeding season, and will often show up in a variety of habitats from swamps and field edges in the east, to riparian corridors and dry canyons in the west.

Among our smallest owls, Saw-whets are slightly longer and a bit more massive than American Robins. They prey almost entirely on small rodents, but will occasionally eat insects, small birds, and amphibians. Strictly nocturnal, they can be extremely hard to find in daytime roosts, or at night unless vocalizing frequently. Separating them on sight from other owls is straightforward generally due to size, although they can be confused with Boreal and Elf owls. Boreal Owls are slightly larger and have a prominent black outline around the face; this is brownish in the Saw-whet. Boreal Owls also show spots on the forehead and crown, while the Saw-whet will show streaking. Elf Owls are considerably smaller than Saw-whets and generally show a darker face with white concentrated above the bill and in the lores and eyebrows. Lack of ear tufts will allow easy separation from screech-owls (Canning, Rasmussen, and Sealey 2008).

During the winter of 2016–2017, large numbers of Northern Saw-whet Owls were observed in east-central Massachusetts. In particular, the areas near Lincoln, Sudbury, and Marlborough had high numbers of wintering birds. Banding results from peak migration in October and November at nearby areas—including Mass Audubon’s Drumlin Farm Wildlife Sanctuary in Lincoln—also showed large numbers of these owls. With so many birds at local hot spots, this proved an exceptional year for studying the extensive vocal array displayed by Northern Saw-whet Owls on their wintering grounds.

Habitat

Northern Saw-whet Owls use a wide variety of habitat during winter. While the canonical location of dense pine stands is always a good place to look (Petersen and Meservey 2003), birds in autumn 2016 were found in dry deciduous forests, even-aged stands of white and red pine, and weedy field edges. Surprisingly, up to half of the birds were found in deciduous swamps, including red maple swamps and other areas containing standing water with stunted deciduous shrubbery.

Vocal Array

The vocal array of Northern Saw-whet Owls is surprisingly broad. While many observers are familiar with the male’s standard advertising song of monotonous toots and other sharp cries or whines, many of us—including the author of this work—are unfamiliar with the variety of barks, chirps, chips, squeaks, and chatters these owls make in interaction with one another or in response to other stimuli. The summary below categorizes various sounds, speculates about their possible meaning, provides visual sonograms of the vocalizations, and—in the Bird Observer Online version of this article—also provides recordings by the author, or other recordists as specified, to help readers become familiar with the diversity of sounds. Chances are you have heard some of these while owling and not been aware of what you were hearing. For an excellent descriptions of Northern Saw-whet Owl sounds, please see Cornell’s Birds of North America entry on this species or P. A. Johnsgard’s North American Owls: Biology and Natural History.

Advertising Song

The male Northern Saw-whet Owl sings the familiar and fairly rapid toot toot toot song most frequently from March through May on the breeding grounds. These monotonous toots are similar in pitch to the whinny of an Eastern Screech-Owl, and distinctly different from the chipping sound of an eastern chipmunk. Be aware that the owls can vary the speed or tempo dramatically, and often they will change the volume during a single bout of song. Usually this song will be given from high in the trees, from an extremely well hidden perch. Of the approximately 80 different auditory encounters I had with Saw-whets during the 2016 season, only about 20 involved primary song. Only two of the owls were visible when singing, and I was able to photograph only one.

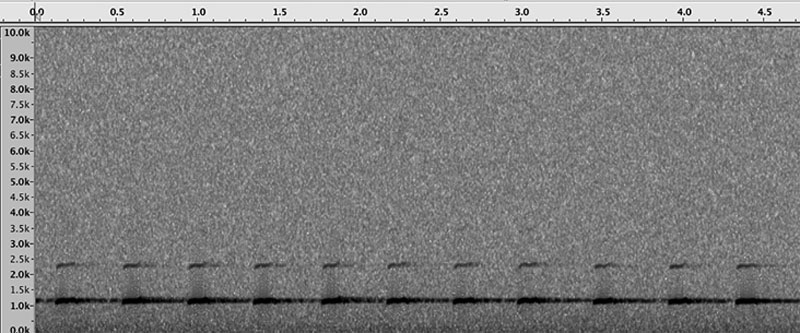

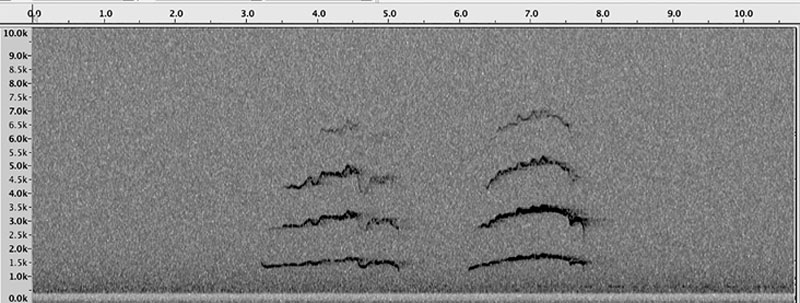

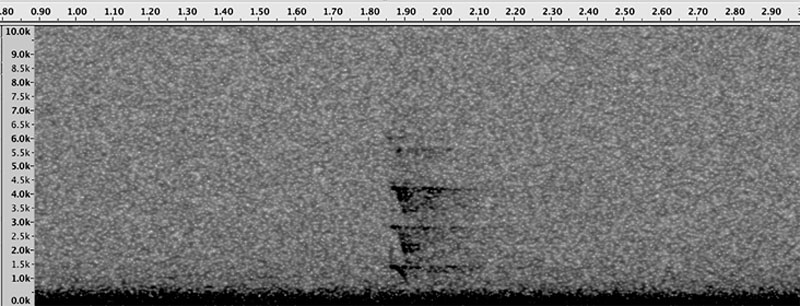

Figure 1. Sonogram of standard advertising song of the Northern Saw-whet Owl.

This song was recorded on March 10, 2017, at Desert Natural Area, Marlborough, Massachusetts. Click the sonogram to hear the recording. Playback issues? Here's a direct link to this audio clip.

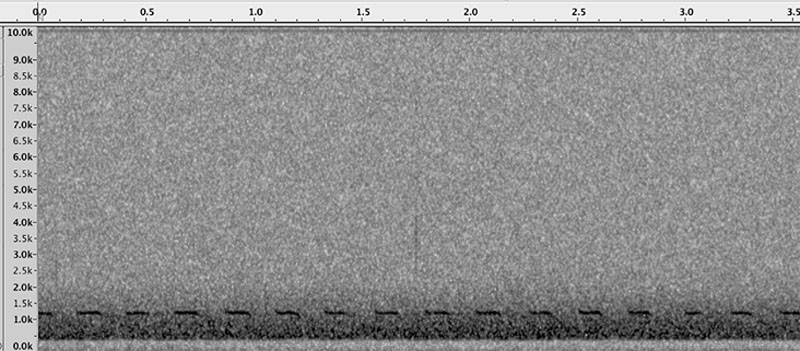

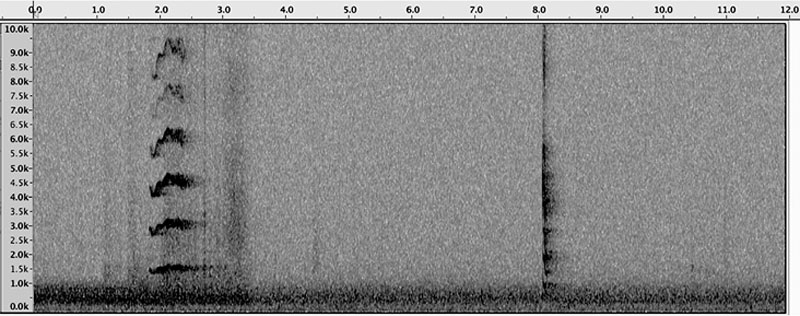

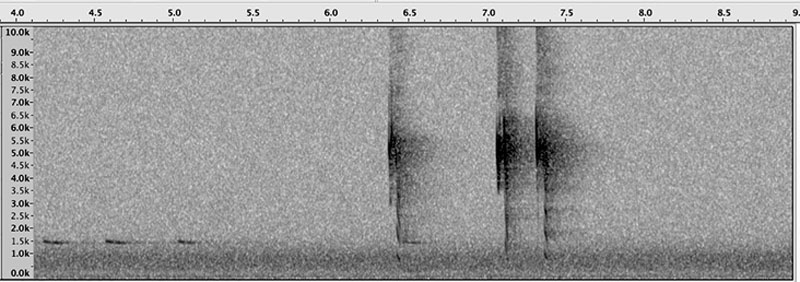

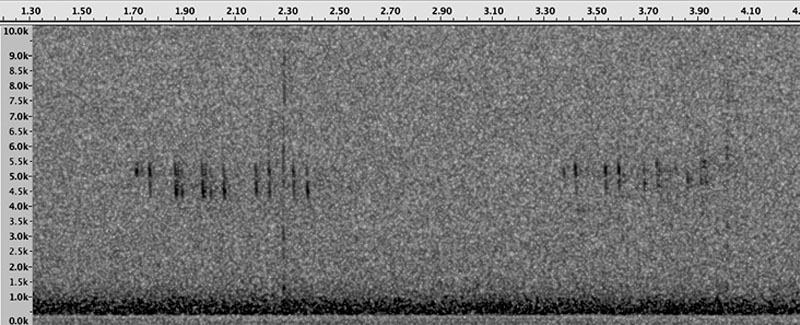

Figure 2. Sonogram of rapid or agitated song of the Saw-whet Owl.

This fast song was recorded on November 23, 2016, Wayne F. MacCallum (formerly Westborough) Wildlife Management Area (WMA), Massachusetts. An Eastern Screech-owl is also singing in clip. Click the sonogram to hear the recording. Playback issues? Here's a direct link to this audio clip.

Cries, Whines, and Shrieks

The most common vocalization of Saw-whet Owls in winter is a sharp cry, wail, whine, or shriek. More than 60% of birds I heard during the winter of 2016–2017 vocalized some form of cry. Often these type of cries will come in bursts of two or three close together, which will sometimes be repeated for several minutes. There is much variation in these sounds, from almost lazy, weak, and soft cries to agitated and extremely loud wails and shrieks. A single cry can often be fairly long in duration—up to a few seconds in length. The owl seems to make this vocalization when annoyed or agitated. It is usually given from a low perch to several meters high in trees. Note that other owls such as Barred, Spotted, Long-eared, and Western Screech sometimes give similar sounds. And perhaps most confusingly, other owls often respond vigorously to these Northern Saw-whet Owl cries, wails, and whines. Here are several examples of Saw-whet cries and wails.

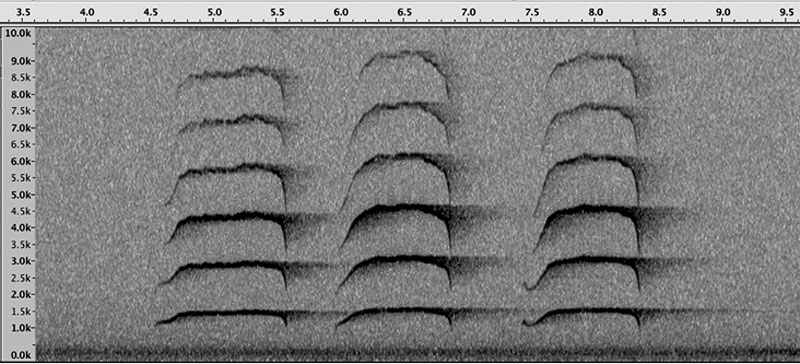

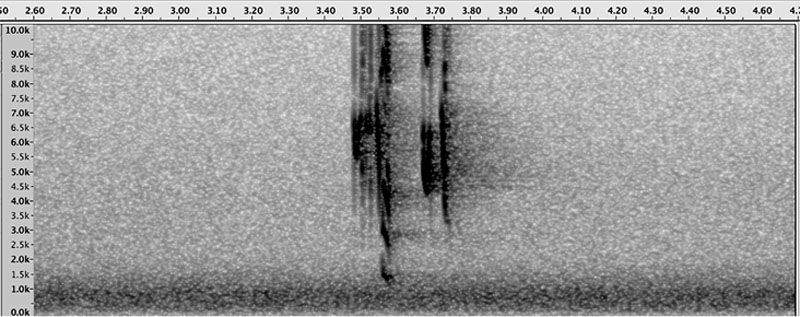

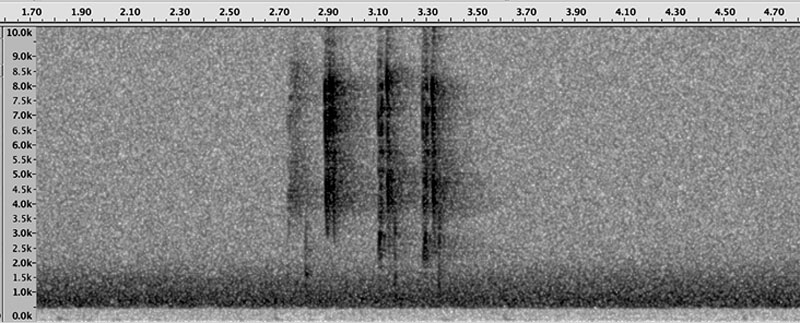

Figure 3. Sonogram of loud wails from Desert Natural Area, Marlborough, Massachusetts, on December 20, 2016. Click the sonogram to hear the recording. Playback issues? Here's a direct link to this audio clip.

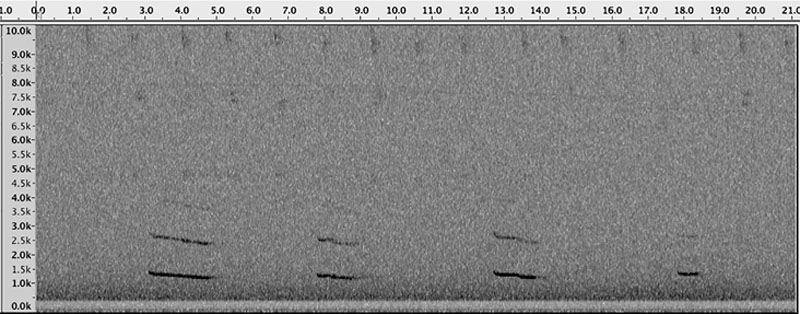

Figure 4. Sonogram of soft wails. These softer wails are from Desert Natural Area, Marlborough, Massachusetts, January 2, 2017. Click the sonogram to hear the recording. Playback issues? Here's a direct link to this audio clip.

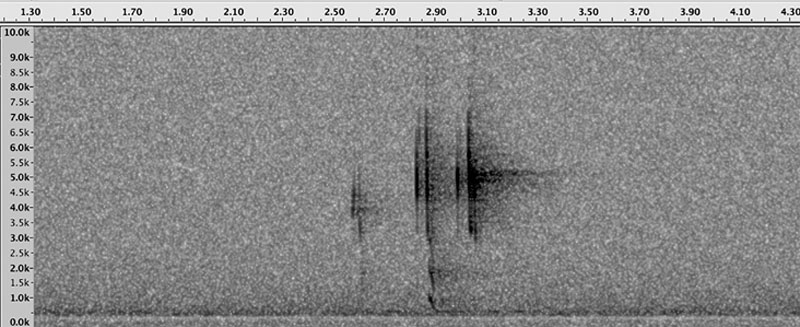

Figure 5. Sonogram of loud, agitated wails. This wail series is from Mount Hopkins, Arizona, January 6, 2017. A Whiskered Screech-Owl is singing at end of recording. Click the sonogram to hear the recording. Playback issues? Here's a direct link to this audio clip.

Figure 6. Sonogram of single wail and then loud bark sound, recorded at Crane Swamp, Northborough, Massachusetts, December 11, 2016. Click the sonogram to hear the recording. Playback issues? Here's a direct link to this audio clip.

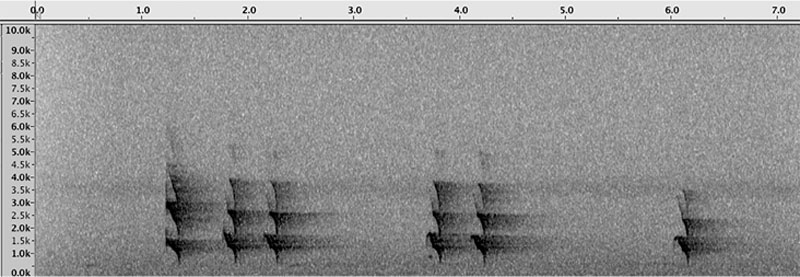

Barks, Chips and Chirps

These less common sounds begin to enter the realm where, upon first hearing or recording them, the response of the author was: “Is that really an owl?” Many of these sounds are surprising and often sound like rodents, insects, or even dogs. The interpretation of these sounds is contact notes and they are often given after birds have flown in to a low perch less than a meter in height to investigate. While recording the sonogram and sound in Figure 8, the author was fortunate enough to see the owl fly in and perch less than three meters away in the base of a small pine.

Soft Barks

A fairly common sound given by Saw-whets is a soft, single, descending bark or a series of these barks. This can vary dramatically from a soft and lazy sound to a series of sharp and agitated barks. The individual barks are short in duration, generally lasting less than half a second. Various references in the literature call this the skiew sound. To the author, it sounds a bit like a small dog or puppy giving soft barks. Or it may be vaguely similar to the sound of tennis shoes squeaking on a gym floor. Saw-whets often give this sound from low perches near the ground.

Figure 7. Sonogram of soft barks recorded by Scott Weidensaul in Pennsylvania, October 26, 2004. This trimmed recording is from Cornell’s Voices of North American Owls. Click the sonogram to hear the recording. Playback issues? Here's a direct link to this audio clip.

Figure 8. Sonogram of a single soft bark, recorded at Desert Natural Area, Marlborough, Massachusetts, February 6, 2017. Click the sonogram hear the recording. Playback issues? Here's a direct link to this audio clip.

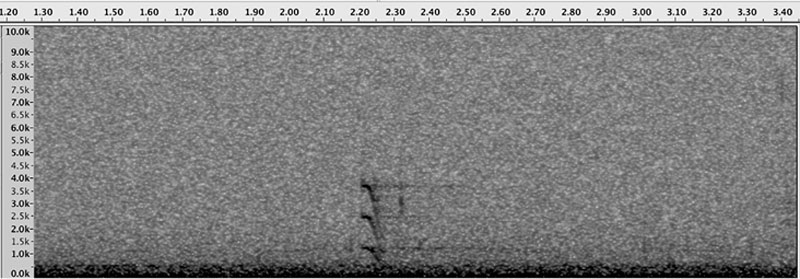

Figure 9. Sonogram of a single, fairly sharp bark, recorded at Desert Natural Area, Marlborough, Massachusetts, February 6, 2017. Click the sonogram to hear the recording. Playback issues? Here's a direct link to this audio clip.

Sharper Barks/Chips

Northern Saw-whet Owls also will respond with sharper bark notes, often in a series of two to five. They sound a bit more like chip notes and are shorter in duration than the barks. These are somewhat similar to chipping notes of eastern chipmunks, warblers, or Northern Cardinals, and are generally given from low perches near the ground.

Figure 10. Sonogram of soft song and loud, sharp chips from separate birds, recorded at Desert Natural Area, Marlborough, Massachusetts, December 6, 2016. Click the sonogram to hear the recording. Playback issues? Here's a direct link to this audio clip.

Figure 11. Sonogram of loud chips and squeaks, recorded at Stirrup Brook, Northborough, Massachusetts, December 22, 2016. Click the sonogram to hear the recording. Playback issues? Here's a direct link to this audio clip.

Figure 12. Sonogram of sharp chips, recorded at Desert Natural Area, Marlborough, Massachusetts, February 6, 2017. Click the sonogram to hear the recording. Playback issues? Here's a direct link to this audio clip.

Chatters and Insect-like Buzzing

From the bizarre to the extreme, Saw-whet Owls will occasionally give a dry chatter or buzzing, which, to the author, sounds most like a cricket or grasshopper. It may also recall the twittering of a flock of Chimney Swifts, but considerably drier. This sound can be given in a fairly long series, often several seconds in duration. To the author, this is an extremely unusual sound to expect an owl to make. Similarly, some of the chips described in the previous section when given even shorter and drier may sound insect- or rodent-like. Some sound like sharp and dry eastern chipmunk notes. These sounds also appear to be contact notes, but curiously are often given from higher perches in dense trees than the barks, chirps or squeaks.

Figure 13. Sonogram of dry, insect-like chatter. These cricket-like sounds were recorded at Assabet River NWR, Sudbury, Massachusetts, December 29, 2016. Click the sonogram to hear the recording. Playback issues? Here's a direct link to this audio clip.

Figure 14. Sonogram of dry chirps/chips, recorded at Desert Natural Area, Marlborough, Massachusetts, December 6, 2016. Click the sonogram to hear the recording. Playback issues? Here's a direct link to this audio clip.

Bill Snaps

On rare occasions, at least during winter, Northern Saw-whet Owls will respond with bill snaps. In seven seasons of owling, the author has heard—but never recorded—this sound only twice. The bill snaps most resemble marbles or rocks clicking together, and are given in a short series.

Sound variation

The descriptions and recordings above should be considered but a small sample of the amazing variability displayed by these owls. For each standard response, there are many variations in pitch, duration, urgency, and volume. eBird’s media search feature allows readers to search through a vast array of sounds, including many from Northern Saw-whet Owls. The link to sounds can be accessed at https://ebird.org/media/catalog.

Northern Saw-whet Owls can be common in Massachusetts in the nonbreeding season. While they are hard to locate in their daytime roosts, observers can encounter these birds by searching and listening carefully for the wide array of sounds they make. Go out next fall and winter to your local hot spot and give them a try!

References:

- Johnsgard, P. A. 2002. North American Owls: Biology and Natural History, 2nd ed. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, pp. 234–241.

- Petersen, Wayne R. and W. Roger Meservey, ed. 2003. Massachusetts Breeding Bird Atlas, Massachusetts Audubon Society. Amherst, Massachusetts; University of Massachusetts Press, pp. 184–185.

- Rasmussen, J. L., S. G. Sealy and R. J. Cannings. 2008. Northern Saw-whet Owl (Aegolius acadicus) in The Birds of North America Online (P. G. Rodewald, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology: https://birdsna.org/Species-Account/bna/species/nswowl Accessed March 15, 2017.

Tim Spahr runs a scientific consulting company focused on asteroid science. When not working, Tim can be found in and around Worcester County chasing warblers, and Red Crossbills if they are nearby.