William E. Davis, Jr.

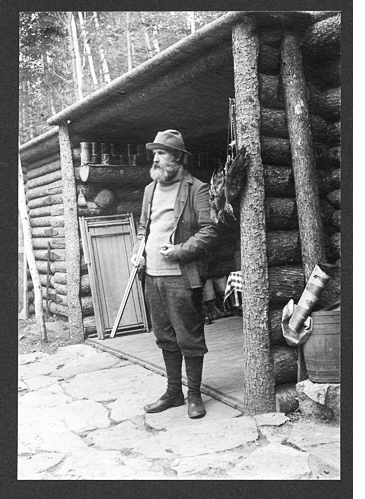

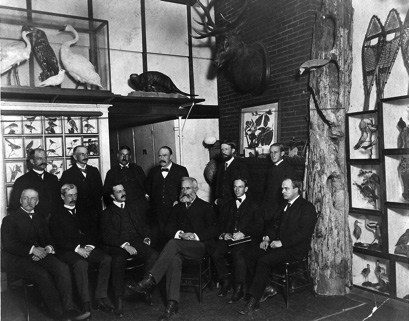

Fig. 1. William Brewster in 1895 at one of his Concord River cabins. Courtesy of the Ernst Mayr Library, Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University.

William Brewster lived most of his life in the greater Boston area and made that area his "patch." Although he became a nationally known and respected figure through his involvement with the Nuttall Ornithological Club, the American Ornithologists' Union (AOU), and his numerous publications, and while he did travel three times to Great Britain and once to the European continent, Brewster nevertheless remained at heart a local New England devotee. He was characterized by wealth and ill health, and these two factors played a significant role in the trajectory of his life. But the single most important factor in his life was his consuming love of nature that took on nearly spiritual dimensions. Around 1890, he purchased a tract of land on the Concord River, in Concord, Massachusetts, later added the adjoining Ball's Hill, and still later added the Barrett farm and another property to bring together about 300 acres that constituted his "October Farm" (Henshaw 1920). He built several log cabins at the riverbank, and he invited his friends to camp with him and roam the fields and forests of his farm. His other patch was Lake Umbagog on the border between Maine and New Hampshire, to which he returned nearly every year for several decades. His wealth allowed him to do whatever he wanted to do, and that was to wander and camp in the woodlands of his patches. In the process he made contributions to the field of ornithology and became revered by those who knew him—an icon in the local ornithological community.

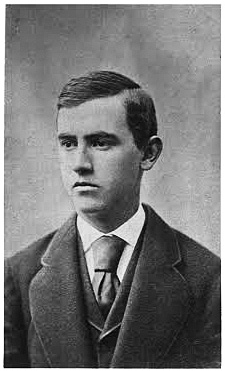

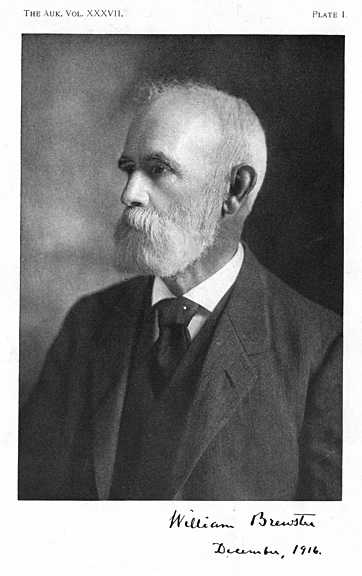

Fig. 2. A young William Brewster. Courtesy of the Ernst Mayr Library, Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University.

The Early Years, the Nuttall Ornithological Club, and the American Ornithologists' Union

William Brewster was born on July 5, 1851. His father, John Brewster, was a successful Boston banker with family roots that traced back to the Mayflower (Henshaw 1920). William ("Will") was the youngest of four children but his sister and two brothers died in childhood, suggesting that Brewster's fragile health may have had a genetic dimension. The family lived in a mansion on the corner of Brattle and Sparks Streets in Cambridge, and there Brewster spent his entire life. He had the normal public school education in preparation for attending Harvard University, but ill health kept him from going to college. He was never robust and suffered from eye problems that prohibited reading for significant periods during his teenage years. He didn't compete in the normal sports but was a good shot and enjoyed horseback riding (Henshaw 1920). As an adult he was over six feet tall and "slow in speech and motion" (French in Brewster 1937). He was something of a recluse, but he made a few local friends; when his father gave him a shotgun at age ten, the open fields and woodlands around Cambridge became the stomping ground for young William and his friends. The father of one of his friends was a sportsman and had mastered taxidermy, so it was natural for young William to be drawn into that sphere.

The collecting of nests and eggs was supplemented by making mounts and study skins of the local birds and through this, Brewster gradually came to know the birds of eastern Massachusetts. Brewster's fascination with nature sprang from his early days in the field with his friends in what was then a rural area in and around Cambridge. His romantic view of nature developed there:

Here the dandelions and buttercups were larger and yellower, the daisies whiter and more numerous, the jingling melody of the Bobolinks blither and merrier, the early spring shouting of the Flicker louder and more joyous, and the long-drawn whistle of the Meadowlark sweeter and more plaintive, than they ever have been or ever can be elsewhere, at least in my experience. (Brewster in Batchelder 1937, p. 10).

In 1869, Brewster, in an agreement instigated by his father, undertook a year's trial at working in the banking world. At the year's end, Brewster found himself unfit for banking, and as a man of independent means, he was free to pursue his ornithological interests. He apparently was uninterested in social matters and politics, and so devoted himself to his obsession with nature and birds (Mitchell 2005).

In 1871, William Brewster, at the suggestion of one of his field companions, Henry Wetherbee Henshaw, invited his group of bird friends, Ruthven Dean, Henry Purdie, and William E. D. Scott, to meet once a week in Brewster's attic to read aloud from Audubon's Ornithological Biography (Audubon and MacGillivray 1831–1839), a companion to his Birds of America plates (1827–1838). Two years later an expanded group decided to formalize their meetings through the formation of a club (Davis 1987). A letter of invitation was sent out to eight of Brewster's associates and on September 23, 1873, Brewster convened a meeting with eight present. They organized a club to be called, at the suggestion of Ernest Ingersoll, the Nuttall Ornithological Club (Club; NOC), with Brewster as President, Purdie as Vice President, Dean as Secretary, and Scott as Treasurer. Thus was formed the first formal ornithological society in the Western Hemisphere.

The Club consisted of Resident and Corresponding Members and quickly acquired national status by recruiting prominent ornithologists as Corresponding Members. By 1877, the number of this group reached nearly a hundred. This base was important in the discussions about starting a journal as a publication outlet for members. The discussions related to this issue, including what should be published and what should not, apparently led to Brewster's resignation as President in March 1875. By February 1876, the matters had apparently been resolved and it was voted to publish a Bulletin, and Brewster was elected as President again, a position he held until his death in 1919. After a brief scuffle, J. A. Allen became the Bulletin's editor, which he was to remain until publication of the journal ceased in 1883. The number of Resident Members rose to 23, the number of Corresponding Members continued to climb, and the first issue of the Bulletin was issued in May, 1876 (Davis 1987).

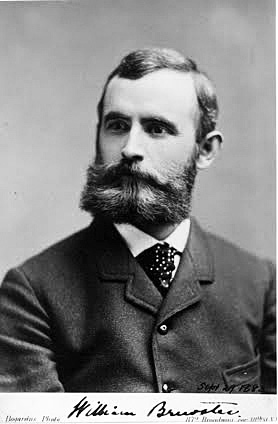

Fig. 3. William Brewster in 1883. Courtesy of the Ernst Mayr Library, Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University.

Everything went merrily along with the Club until 1880 when a gradual deterioration occurred in attendance, until by 1886 some meetings were not held because of lack of a quorum. In a February 10, 1883, letter to Charles Foster Batchelder, Brewster indicated his despair with the Club's situation and was beginning to think about bigger things:

The home members, with the exception of Purdie and Allen, don't seem to care a hang whether the Club and its organ live or die. We had our third blank meeting last Monday; only four members present. I often feel tempted to work on a plan I have had in mind for some time, one which includes the dissolution of the Club and the organization of a new association which shall consist only of persons who care enough about ornithology to do their share of the work. . . . An American Ornithologists' Union, limited to, say, to twelve members, could, I think, be made up in such a way as to be a very strong institution. (Quoted in Batchelder 1937, p. 46).

Such ideas were in the air, and it was inevitable that ornithologists' thoughts would turn to a national organization. The last half of the nineteenth century witnessed a professionalization of American science. Government-sponsored explorations of the western United States and newly-built railroads aided the establishment of networks of collectors and provided easier access to regions previously impenetrable. Museums and their staff were expanded to handle the influx of millions of new specimens, and the number of natural history journals rose from two in 1870 to nearly 40 by the mid-1890s. The time was ripe for a national organization for professional ornithologists and the huge cohort of serious amateurs.

Brewster, together with J. A. Allen and Elliot Coues (pronounced "Cows"), set about organizing a meeting of prominent ornithologists and issued invitations for the meeting in New York in September 1883. Two dozen of North America's most prominent ornithologists met at the American Museum of Natural History. Brewster called the meeting to order, but was upstaged by Coues, who was elected Acting Chair of the meeting. Brewster was apparently unhappy with this surprise and clearly thought that he would fill that position. Coues, however, was probably a better choice, for his highly aggressive nature if nothing else. The meeting was a great success, and the American Ornithologists' Union (AOU) became a reality with the provisional bylaws and constitution presented by Brewster, Allen, and Coues. Six committees were established and memberships of the committees appointed. The last day of the meeting, Brewster reported, when the topic of a journal for the new organization came up, that as President of the NOC, "he was authorized to say, though he could not do so officially" that the NOC would offer the "prestige and subscription list" to the AOU (Barrow 1998). The minutes of the next NOC meeting tell the story:

Mr. Brewster gave an account of the proceedings of the recent convention of ornithologists . . . stating in brief the aims and purposes of the organization called the American Ornithologists' Union . . . Some discussion ensued as to the continuing of the Nuttall Club on its present basis; and in view of the organization of the Am. Orn. Union, and its proposal to issue a quarterly journal of ornithology, which would thereby leave the ‘Nuttall Bulletin' in a manner a competitor in the same field, the question of continuing its publication was considered. Upon motion a vote was passed referring the subject to the Council. All the members except one of the Council being present, and having already expressed themselves in favor of discontinuing the ‘Bulletin', Mr. Brewster as Chairman of the Council advised to discontinue the publication. . . . the Club voted to stop printing the ‘Bulletin' . . . and to offer to the American Ornithologists' Union our good will and subscription list, to place the ‘Bulletin' in the Council of the Union, with the tacit understanding that the new serial of the Union shall be ostensibly a second series of the Nuttall ‘Bulletin.'

Thus the Bulletin became The Auk, and J. A. Allen became its Editor and William Brewster was appointed an Associate Editor. The Nuttall Ornithological Club survived giving birth and after 1886–1887, when Brewster had built a museum on his property to house his vast collection of bird skins and mounts, he hosted the meetings of the Club in his museum. Under Brewster's leadership, the Club grew in membership and prestige.

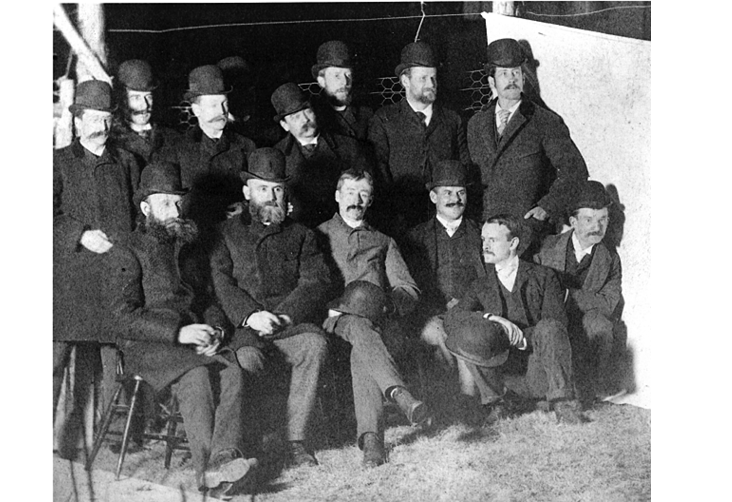

Fig. 4. Group of Nuttall Club members near the Brewster Museum in 1889. Listed as present but not identified in the photo, were: William Brewster, H. W. Henshaw, C. F. Batchelder, F. Bolles, H. M. Spelman, J. A. Jefferies, Edward A. Bangs, A. P. Chadbourne, H. A. Purdie, A. M. Frazer, and Outram Bangs. Courtesy of the Ernst Mayr Library, Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University.

Although Brewster served as President of the new Union from 1895–1898, his greatest influence on the Union and on American ornithology was probably in his service to the most important and influential of the AOU committees, the Committee on Classification and Nomenclature, to which he had been appointed at the inaugural meeting. The Committee's goals were to establish a standardized nomenclature for North American birds and produce a Checklist of North American birds. In addition to Brewster, the powerful Committee included Coues, Allen, Henry W. Henshaw (a great friend of Brewster), and Robert Ridgway who was a leading ornithologist at the Smithsonian Institution. Allen and Coues were on a subcommittee to deal with the code of nomenclature, and Brewster, Henshaw, and Ridgway were in charge of determining the status of subspecies and species (Lewis 2012). The Committee was to break with English ornithologists on several major issues including adopting the 1758 version of Linnaeus's Systema Naturae, rather than the 1766 version favored by the British, and the adoption of a trinomial system of nomenclature that identified subspecies. Brewster was to be an influential and outspoken member of the Committee, and he remained on this important committee until his death in 1919.

Love of Nature, Brewster's Journals and Publications

"The foundation of William Brewster's life was an intense love of nature. Like some delicately adjusted apparatus, his whole being responded to the influences of the open" (Chapman 1919). Brewster from an early age kept a detailed journal of his excursions into the field that became the basis for many of his publications and for the sometimes lyrical passages that were published posthumously in October Farm (French 1936) and in Concord River (Dexter 1937). His love of nature is clear in a passage in the former:

It is in the broad woodlands that one may see October to the best advantage. There is a ripe golden quality there that I miss in the open places where the grass is still as green as in midsummer. The dropping of acorns and chestnuts is an ever-present sound there and the squirrels are all busy with their annual harvest. Their chatter, chuckling, and rustle keep perfect accord with the screaming of the Blue Jays and the ceaseless whisper of the falling leaves. (October Farm, p. 14)

His journals illustrate the detailed observations that were to typify his professional writings, particularly as he moved progressively to the study of the living bird:

As I watched a Shrike it flew from the topmost spray of a small maple into some alders and alighted on a horizontal stem . . . as I afterwards found, the snow had thawed quite down to the ground, leaving a trench . . . into which the Shrike, after peering intently for a moment, suddenly dropped with fluttering wings and wide opened tail,

Within a second or less it reappeared, dragging out a Field Mouse of the largest size. The moment it got the Mouse fairly out on the level surface of the snow it dropped it apparently to get a fresh hold . . . The Mouse, instead of attempting to regain its run way, as I expected it would do, turned on its assailant and with surprising fierceness and agility sprang directly at its head many times in succession, actually driving it backwards several feet although the Shrike faced the attack with admirable steadiness and coolness and by a succession of vigorous and well aimed blows prevented the Mouse from closing in.

At length the Mouse seemed to lose heart and, turning, tried to escape. This sealed its fate for at the end of the second leap it was overtaken by the Shrike, who caught it by the back of the neck and began to worry it precisely as a Terrier worries a rat, shaking viciously from side to side. (October Farm pp. 28–29)

Fig. 5. Nuttall Club meeting at the Brewster Museum, ca. 1900. Front row, left to right: Walter Deane, C. F. Batchelder, Francis H. Allen, William Brewster (Club President 1873–1875, 1876–1919), Glover M. Allen, and Jewell D. Sornborger. Standing, right: Reginald Howe; remainder of standing unidentified. Courtesy of the Ernst Mayr Library, Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University.

Brewster published his first note in 1868 in the American Naturalist on a Red-winged Blackbird sporting an orange crescent on its breast (Brewster 1868). It was the first of more than 350 papers and monographs he would publish in his lifetime, most of them (80%) by the year 1900. Aside from a few mammal, plant, and miscellaneous notes his publications were all bird or ornithologist related. His ornithological work was similar to that of most scientifically-oriented amateur ornithologists—he was a product of his times. About 40% of his papers dealt with bird distribution and arrival and departure dates, mostly reports of sightings of vagrants. About 23% dealt with natural history subjects, such as breeding or feeding behavior that reflected observations he made on living birds, for example his extensive natural history study of the Swainson's Warbler (Brewster 1885a) or his study of the feeding behavior of Northern Flickers (Brewster 1893). An additional 15% were systematic papers that involved naming of new species or subspecies, hybrids, or nomenclature problems. Reviews of other peoples work were another 9%. The remaining 13% I classified as miscellaneous, and included the occasional mammal or plant paper, obituaries, letters to newspapers, reports of AOU committees, and a few papers on bird protection that he published near the end of his life. Generally lacking were theoretical papers in the general field of biology or on evolution, a situation in contrast to several of his colleagues including J. A. Allen (Davis 2005). He lacked the formal biological training of colleagues such as Allen and Coues, and this may have been the key to his low output of theoretical work.

There were exceptions, however. His short monograph on bird migration (Brewster 1886) was a landmark paper on this subject and was the first Memoir published by the Nuttall Ornithological Club (the NOC still publishes them). It was a two-part paper that included a first part in which he reported his observations on nocturnal migration at a lighthouse in the Bay of Fundy and a second part that dealt with theories of bird migrations and the facts available to support them. His 1906 Memoir Birds of the Cambridge Region of Massachusetts was regarded as a classic for its long-term intensive study of a small region (Brewster 1906). Some of his short papers were theoretical in nature, for example his 1883 paper on the movements of birds in winter, which included suggested causes for the irregular movements of birds such as Snowy Owls and Pine Grosbeaks (Brewster 1883). Another of his important regional works, on Lake Umbagog, was edited and published posthumously in four volumes (1924, 1925, 1937, 1938). Volumes 1 and 2 were edited by Samuel Henshaw, volumes 3 and 4 by Ludlow Griscom.

It may be that Brewster realized his limitations in the realm of the theoretical. We see a hint of this in the following letter to Frank Chapman:

Dear Friend:

I have just read your paper on West Indian birds & bird life with the keenest pleasure and interest. It is far & away the best thing you ever have done and raises you at one bound, I should say, to the plane of such men as [J. A.] Allen and [C. Hart] Merriam and distinctly above that of all other living American ornithologists. Your chapter on the affinities and probable derivation of West Indian bird and mammal life is, of course, what I directly refer to. It is compact, philosophical and convincing to a degree. I have long predicted such progress and development on your part and now that it has come I rejoice exceedingly and congratulate you with my whole heart. . . (2 Jan 1893, Brewster letter to Frank Chapman)

Brewster did pretty much what he wanted to do, and his publications and journals suggest that being in the field was most important to him.

Brewster's Friends, Colleagues, Influence

Many descriptions of Brewster as an austere, formidable, and Jovian character came from people who knew him only late in life and mostly within the formal atmosphere of Nuttall Ornithological Club meetings at his private museum. In his younger years, up to about 1900, when he was most active in the ornithological endeavors, he had close personal friends and relationships with colleagues that indicate a warm personality and a sense of humor. One of his closest professional and personal relationships was with Frank Chapman, head of the ornithology department at the American Museum of Natural History, who, among his many accomplishments, initiated the Christmas Bird Counts near the turn of the twentieth century and founded and edited the journal Bird-Lore, which eventually became Audubon Magazine. Brewster accompanied Chapman on several collecting expeditions, including those far afield for Brewster, to the Suwannee River of Georgia and northern Florida and to Trinidad. Brewster's correspondence with Chapman indicates a warm and collegial relationship and a sense of humor. For example, in remarking about a trip in which Chapman visited Ball's Hill, Brewster provides evidence of his deep love of being in the field as well as a friendly and appreciative relationship with Chapman:

. . . It is a pleasure to know that you enjoyed your stay here so much but I am quite sure that you did not enjoy it more than we enjoyed having you with us. . . There are so few who appreciate the woods and birds in just the way that I appreciate them. . . it is a great delight to me to be in the woods with a man after my own heart—when I find him. (26 May 1890, Brewster letter to Chapman)

Fig. 6. William Brewster in 1916. Courtesy of the Ernst Mayr Library, Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University.

Brewster made many collecting trips with his friends. In 1874, he collected with Ruthven Deane and Ernest Ingersoll in West Virginia. In 1878, he collected with Robert Ridgway at Mount Carmel in Illinois, and he was part of a group that in 1881 collected in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. In 1882, he joined J. A. Allen in Colorado, and in 1883, he traveled to South Carolina where he was assisted by Arthur T. Wayne while carrying out his studies of Swainson's Warbler. For 20 years he was accompanied in the field at home by his manservant, "Mr. Gilbert," a black man with whom he became good friends and who in all probability was the photographer who took the more than a thousand glass-plate photographs that are attributed to Brewster (Mitchell 2005). For a decade, Brewster also hired his friend Walter Deane as his personal secretary and museum assistant. These companions in the field contributed to Brewster's high productivity—wealth has its advantages. He also hired professional collectors to work areas for him that he apparently could not or did not wish to visit. For example, Frank Stephens collected for Brewster in Arizona and California in 1881 and 1884, and R. R. McCleod collected for him in 1883–1885 in Arizona and Mexico (Henshaw 1920). These professional collectors not only helped Brewster acquire the largest private collection of birds in the United States, but their specimens became the basis for many of his publications, for example a paper on birds collected by Stephens (Brewster 1885b).

Brewster held several positions that provided him with authority and influence. From 1880–1889, he was curator of the bird and mammal collections of the Boston Society of Natural History, and from 1885–1900, he held the same position at the MCZ. From 1900 until his death in 1919, he curated just the birds. These positions gave him status and connections to powerful people in other museums. For example, he had influence with the head of the Museum of Comparative Zoology (MCZ), Alexander Agassiz, who was the son of the Museum founder, the legendary Louis Agassiz. Brewster had influence that affected museum politics on the national level.

Bird Protection and the Conservation Movement

Brewster was always interested in the movement for the protection of birds, which developed into the modern conservation movement. He was well aware of the problems caused by development and wholesale destruction of forests. He did not return to his beloved Lake Umbagog region because of inroads of people and their destruction. He was appointed to the AOU's Committee on Bird Protection. He was the President of the Massachusetts Audubon Society, the first of the regional Audubon societies (Walton and Davis 2010); and he later served as a Director for the National Association of Audubon Societies, the forerunner of the National Audubon Society. He served on the Board of Directors of the Massachusetts Fish and Game Protective Association and was its President for two years. He was a member of the Advisory Committee of the American Game Protective and Propagation Association from 1911 until his death (Henshaw 1920). He was an avid hunter throughout his life and steadfastly defended the rights of scientific collectors, but he understood the constraints that would be necessary to produce sustainable harvests.

What Made Brewster the Icon That He Became?

Brewster reaped many rewards for his contributions, including an honorary A.M. degree from Amherst College in 1880 and an honorary A.M. from Harvard in 1889. Why did Brewster become so successful? Part of the answer comes from his personality, part from his wealth, and part from being at the right place at the right time. He was a tall, handsome man with character traits that, at least in last half of the nineteenth century, were considered admirable. He didn't drink tea or coffee, rarely used alcohol, and in today's world might be considered a bit boring. But the people he worked with agree that he was an admirable person. Witmer Stone summed it all up in a 1919 note:

Great as were his attainments as an ornithologist it was not these alone that gained him the wide recognition that he received. His fair and impartial judgment of all questions that came before him created a profound and widespread respect for his opinion; his keen and unconcealed delight in everything out of doors, . . . was contagious and inspiring; while his uniform courtesy and kindliness to young student and master alike, endeared him to all with whom he came in contact. . . . Probably he himself never realized the part he played in shaping the ornithological activities of others, and his influence upon the development of American ornithology cannot easily be measured. (Stone 1919)

Even considering the early twentieth century hyperbole, it is clear that Brewster had a powerful personality that had an impact on the lives and careers of those who encountered him. But had he not been born in the right time and at the right place, it seems doubtful if he would have achieved such greatness. He reached early manhood at a time when interest in science and natural history was flooding the American scene. The American Ornithologists' Union, or a similar one with a different name, would have become reality, probably within a few years, because the time was right and many of America's ornithologists shared Brewster's views. But only Brewster and his cohort of Cambridge friends brought it to reality, through the founding of the Nuttall Ornithological Club and its Bulletin, thus forming the backbone of Brewster's success and greatness.

Literature Cited

- Audubon, J. J. 1827–1838. Birds of America. London: Robert Havell.

- Audubon, J. J., and W. MacGillivray. 1831–1839. Ornithological Biography, or an Account of the Habits of the Birds of the United States of America. 5 volumes. Edinburgh, Scotland.

- Barrow, M. V., Jr. 1998. A Passion for Birds, American Ornithology after Audubon. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Batchelder, C. F. 1937. An Account of the Nuttall Ornithological Club 1873–1919. Memoirs of the Nuttall Ornithological Club, No. 8. Cambridge: Nuttall Ornithological Club.

- Brewster, W. 1868. A Variety of Blackbird. American Naturalist 2(June): 217–218.

- Brewster, W. 1883. The Movements of Certain Winter Birds. Bulletin of the Nuttall Ornithological Club 8: 245–246.

- Brewster, W. 1885a. Swainson's Warbler. Auk 2: 65–80.

- Brewster, W. 1885b. Additional Notes on Some Birds Collected in Arizona and the Adjoining Province of Sonora, Mexico, by Mr. F. Stephens in 1884; with a Description of a New Species of Ortyx. Auk 2: 196–200.

- Brewster, W. 1886. Bird Migration. Memoirs of the Nuttall Ornithological Club, No. 1. Cambridge: Nuttall Ornithological Club.

- Brewster, W. 1893. A Brood of Young Flickers (Colaptes auratus) and How They Were Fed. Auk 10: 231–236.

- Brewster, W. 1906. Birds of the Cambridge Region of Massachusetts. Cambridge: Nuttall Ornithological Club, Memoir No. 4.

- Brewster, W. 1924, 1925, 1937, 1938. The Birds of the Lake Umbagog Region of Maine. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology 66: Parts I–IV.

- Chapman, F. M. 1919. William Brewster, 1851–1919. Bird-Lore 21(5): 277–286.

- Dexter, S. O., ed. 1937. Concord River, Selections from the Journals of William Brewster. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Davis, W. E. Jr. 1987. History of the Nuttall Ornithological Club 1973–1986. Memoirs of the Nuttall Ornithological Club, No. 11. Cambridge: Nuttall Ornithological Club.

- Davis, W. E. Jr. 2005. J. A. Allen: The Shy and Retiring Giant. Bird Observer 33: 30–41.

- French, D. C. ed. 1936. October Farm: From the Journals and Diaries of William Brewster. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Henshaw, H. W. 1920. In memoriam: William Brewster. Auk 37: 1–27.

- Lewis, D. 2012. The Feathery Tribe, Robert Ridgway and the Modern Study of birds. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Mitchell, J. H. 2005. Looking for Mr. Gilbert, the Reimagined Life of an African American. Washington D.C.: Shoemaker Hoard.

- Stone, W. 1919. Brewster, William. Auk 36: 628.

- Walton, R. K., and W. E. Davis, Jr. 2010. Massachusetts Audubon Society: The First Sixty Years. Pp. 1–63 in Contributions to the History of North American Ornithology, Volume III. Memoirs of the Nuttall Ornithological Club, No. 17. Cambridge: Nuttall Ornithological Club.

Note: An expanded version of the biography has been published as a chapter in Volume IV of the series Contributions to the History of North American Ornithology, W. E. Davis, Jr., editor, published by the Nuttall Ornithological Club, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Copies of this book can be purchased from Buteo Books at https://www.buteobooks.com/mm5/merchant.mvc?Store_Code=BBBAO&Screen=PROD&Product_Code=CHNA4 or on their toll free line: 800-722-2460.

William E. (Ted) Davis, Jr. has been on the Bird Observer Editorial Staff for more than three decades and is an Emeritus Professor from Boston University. He is an ornithologist who has done most of his research fieldwork in Australia.