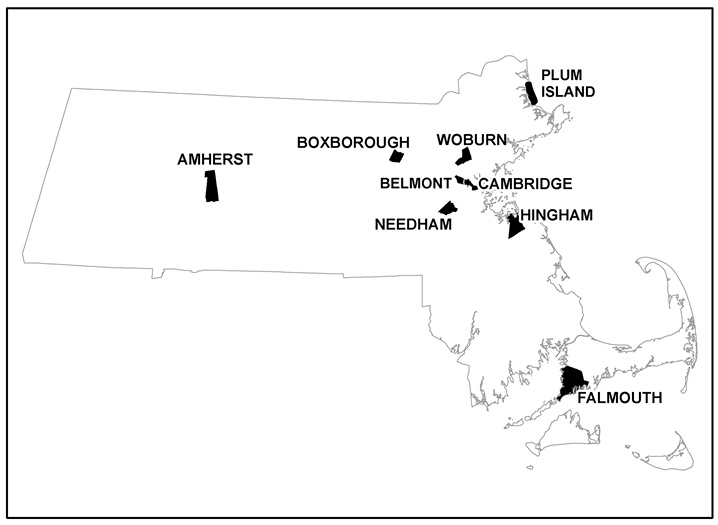

Bird Observer Staff and Board Members

East Falmouth Covid-19 Birding Surprises and Delights

Nate Marchessault

The last several months of 2020 have resulted in drastic changes for us all, including changes to our birding routines. As someone accustomed to driving relatively long distances to go birding, I found the concept of distance quickly morphed into one that was hyperlocal. Driving more than twenty minutes seemed too far and the ideal distance gave me just enough time to gulp down a cup of coffee in the morning. Being a relatively new resident of East Falmouth, I had an abundance of new locations to explore, and one of the greatest surprises to me was the sheer quantity and the size of some of these areas.

Closest to home and by far the largest is the Mashpee National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) complex, which comprises nearly 6,000 acres of conservation land. Johns Pond Park, one of my favorite local haunts, is contained within this complex and begins along the shoreline of Johns Pond. A vast network of trails meanders through various types of forest, along a small pond's edge, and through old cranberry bogs that are in various stages of early succession. The combination of habitats and contiguous conservation land makes for a great birding area with an excellent diversity of bird species. The early spring was my favorite here, where during an early morning walk I would almost always hear hooting Barred and Great Horned owls, singing Hermit Thrushes, and drumming Ruffed Grouse.

Just below the southernmost terminus of Mashpee NWR, South Cape Beach quickly became another favorite place to visit. In addition to walking along the beach, one can explore two trails that are vastly different from each other. The Great Flat Pond Loop begins on a short boardwalk along the salt marsh edge and enters the woods where it eventually reaches Flat Pond, a large salt pond with a northern end dominated by cattails. During several visits here, one of my favorite observations of the spring was a Marsh Wren singing in a small wetland dominated by highbush blueberry. I had hoped the bird would attempt to breed because I found it hard to envision what a Marsh Wren nest would look like in a blueberry bush but alas, the bird eventually came to its senses and moved on. The second trail is Dead Neck Trail, which I first explored during Bird-a-thon. Friday evening, May 15, I began Bird-a-thon looking at a Saltmarsh Sparrow that I had previously staked out, and decided to walk the trail—a sandy hike through the dunes that ends where the ocean meets Waquoit Bay—to see what other estuarine or seabird species I could come up with. I had envisioned the walk being a slog since there was a cold, stiff breeze coming from the west. Much to my surprise, as I started my walk the wind died out, giving way to an utter calmness, the radiant, setting sun gently warming. The sheer tranquility of the moment made it impossible to maintain the rush and anxiety of Bird-a-thon, and along the slow, mile walk out to the end of Dead Neck I watched as Horned Larks sang their sweet and delicate songs on the wing and Green Herons hunted in the small salt ponds.

One of humankind's greatest strengths is its adaptability, and the situation we have been in over the last several months serves as a prime example. From adapting the workplace to socializing digitally to birding, we as a species have come up with ways to do these things safely and responsibly. In the case of birding, I believe we have adapted to keep us sane. Luckily, birding is one of the most adaptable hobbies there is; you can travel around the world or not leave home, you can have tons of gear or not use any, you can do it in large groups or do it alone—and for that we are most fortunate.

The Middlesex Canal, Woburn, Massachusetts

Regina Harrison

When the COVID-19 stay-at-home order went into effect, my husband and I found ourselves working from home in North Woburn, where we have lived since 2012. Right away we decided to make a lunchtime walk part of our daily routine and to use those walks to explore parts of the surrounding area where we had never been before. Just up the street from our house, a wide pathway along a narrow waterway leading into some woods beckoned. I had always been curious about those woods but had not previously explored them because I was not certain about the safety of walking there alone. All I knew about the place was that the waterway was part of the Middlesex Canal, according to a sign at the path's far outlet, near the rotary at Exit 35 off Interstate 95/Route 128. The pathway begins at the fork of School and Merrimack streets and ends in the parking lot of the yellow mansion that houses Sichuan Garden and the Baldwin Bar.

It was late March when we first walked down that pathway. It held the legacy of decades of human activity in the form of trash, old tires, and signs of a homeless encampment. There were many invasive plants present, with bittersweet vines galore festooning the trees, but there were also birches, maples, and oaks, some blueberry bushes, and other signs of native plants. All were bare then, but the woods contained promise in the form of plenty of the local winter birds: Blue Jays, Northern Cardinals, Downy and Hairy woodpeckers, Northern Flickers, and a Yellow-bellied Sapsucker. As spring rolled along, these birds were joined by Red-winged Blackbirds, Common Grackles, and American Robins. I noted what looked like some variety of cherry tree getting ready to bloom. Then, finally, on a glorious mid-May afternoon, there they were—spring migrants. Throughout the month of May, the tangled understory lining the path provided wonderful eye-level views of Northern Parulas, Black-and-white Warblers, Palm Warblers, American Redstarts, Blue-headed Vireos, Hermit Thrushes, Baltimore Orioles, Grey Catbirds, and, of course, many Yellow-rumped Warblers gleaning insects from the blooming cherry blossoms. A female Mallard is now raising her brood in the secluded waterway, and a Great Blue Heron regularly visits. All of these riches had been just around the corner from my house for years and I had had no idea. It was a revelation and a gift, a little local patch as consolation for losing the regular spring destinations.

Research on the Middlesex Canal, built in the late 1700s and early 1800s and reaching from Boston to Merrimack, New Hampshire, reveals that many of my regular birding destinations were once along the canal's route, which traveled through Woburn roughly along present-day Route 38 to Horn Pond, down the Aberjona River to the Mystic Lakes, then along the Mystic River to the canal's ultimate end point in Charlestown. Traces of the old canal can be seen all along its route, though much has been filled in and paved over. A dam built in North Billerica to control water flow through the canal flooded hay meadows farther up the watershed, which became permanent wetlands and now form part of the Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge. As I walk along this little remnant of the once-mighty canal, I am grateful to feel its connection to these other places, making them feel less distant from me, and for showing me that staying at home could be as rewarding as a drive to any of those other places. I look forward already to next spring on the Middlesex Canal.

Covid-19 Birding in Belmont, Massachusetts

Jeffrey Boone Miller

Fig. 1. Northern Rough-winged Swallow at Clay Pit Pond in Belmont on May 3, 2020. Photograph by Jeffrey Boone Miller.

Due to the pandemic, my work closed on March 16, 2020. Soon thereafter, the major birding sites around our suburban home in Belmont, Massachusetts, either closed—Mount Auburn Cemetery—or became too crowded for comfort—Fresh Pond. So, for almost three months, I have birded only in my backyard and on daily walks through local streets and to Clay Pit Pond near our high school. If one is willing to count a neighbor's chickens, as of June 12, my species count for the pandemic era stands at 67. These birds—all seen within a mile of our house—have brought welcome moments of serenity and contemplation. Some highlights follow.

Through the end of March, "Lefty," a Dark-eyed Junco with a distinctive white wing feather (Miller 2019), visited our feeder for the third consecutive winter. In March and April, a red phase Eastern Screech-Owl appeared consistently in a nearby maple tree and became a neighborhood attraction. On March 18, an aggressive Cooper's Hawk harassed a pair of Red-tailed Hawks that were perched in our backyard apple tree. At Clay Pit Pond, a pair of Eastern Kingbirds carried out a courting flight just over my head on May 6, and my discovery of two Prairie Warblers on May 15 doubled my lifetime total for that species. On the mornings of May 18 and 19, I was enveloped by flocks of Cedar Waxwings with their always endearing susurrations and food-sharing behaviors.

Beginning with their arrival on May 3, I also regularly observed a pair of Northern Rough-winged Swallows that frequented the west end of the pond. Particularly during the first half of May, the two birds were usually calling back and forth, and one sometimes perched nearby (Figure 1). On multiple occasions I saw one either enter or exit a four-inch-diameter pipe built into a rock wall where Wellington Brook enters the pond. I hoped they might be using the pipe as a nest, but I did not see the swallows carry nesting material or food and, as of June 12, no youngsters have appeared. Nonetheless, if, as Shakespeare wrote in Richard III, "True hope is swift, and flies with swallow's wings," then I have lived with hope this spring and I am grateful.

Reference

A New Appreciation for Bird-a-thon in Boxborough

Rita Gibes Grossman

Watching the spring rituals of returning migrants—especially the Carolina Wrens now nesting in our propane tank cover—has been calming amid the uncertainty of the Covid-19 pandemic. Being hard-wired for birding has been a source of comfort and discovery, especially for Mass Audubon's Bird-a-thon. Every year in mid-May during the height of spring migration, Mass Audubon sponsors a friendly, fundraising bird count competition. Usually I would head to the northwestern corner of Massachusetts and spend the night in Florida. This year, everything changed. All species counts had to be accomplished at home or at locations within cycling or walking distance to comply with Covid guidelines. Fortunately, I live in Boxborough where everyone is welcome to walk, hike, and birdwatch. I managed to visit seven conservation areas by walking eleven miles and biking fourteen. Not all of the species I anticipated made an appearance during the twenty-four-hour count window, but the ones that did felt notable to me as if I were rediscovering or seeing them as never before.

At Rolling Meadows Conservation Area, an Ovenbird and a Swainson's Thrush gave me a lengthy viewing and both seemed as interested in checking me out as I them. Ovenbirds, despite being common to every patch of hardwood forest and readily heard with their teacher, teacher, teacher strident call, can be remarkably difficult to spot. As ground nesters and low canopy and below occupants, these warblers have a voice that seems to project beyond its small source. While walking the main wooded trail, I caught movement in low branches and there was the Ovenbird—constantly moving but giving me a brief penetrating look at its white eye ring, stunning streaked chest, and brown and orange striped crown as it rapidly and quietly foraged for insects. It was a FOY (First of the Year) sighting for me despite having heard many.

With pure luck, as this species tends to be heard and not seen, I found the Swainson's Thrush perched on a sapling branch at eye level on the lower trail near the stream. It seemed as if we both were processing each other's presence. Catharus ustulatus was named after the English ornithologist William John Swainson probably in the late 1700s. A shrub nester, the Swainson's Thrush winters in Central and northern South America and breeds in the forests of North America, so the only option for local sightings is during migration. Although these species are common and not threatened, seeing them this year felt different. I had other recent sightings of Swainson's Thrushes in our yard and an Ovenbird continues to define his territory in the woods west of our house, but seeing them as I did felt like a reward for local Bird-a-thon observation.

Additional sighting highlights included Brown Thrasher, Eastern Towhee, and Prairie Warbler near Beaver Brook Road on the Cisco System's campus, which has accessible conserved parcels; Chestnut-sided Warbler at Patch Hill Conservation Area; Green Heron and Winter Wren on the Hager Land trails; Yellow-rumped Warblers and Northern Parula at Inches Woods; and Bobolink and Northern Waterthrush at Steele Farm. I birded the Boxborough Station Wildlife Management Area (WMA) owned by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts for the nesting Great Blue Herons, Osprey, and Eastern Kingbird, among many others. The Wood Ducks and Hooded Mergansers have been quite visible at the WMA, except neither species cooperated for the count. At the end of the count I had 72 species, which I had hoped would be higher. But still I felt a sense of accomplishment and had counted all without burning fossil fuels.

If you have reason to be near Boxborough, a ten-square-mile, inland, headwater environment with ponds, streams, wooded uplands, and a few meadows, there are excellent birding destinations. The town's website includes the local conservation lands with trails as downloadable PDF maps and a link to OpenStreetMap, an interactive, free app for your smart phone. See https://www.boxborough-ma.gov/conservation-commission/pages/conservation-trail-maps.

Through the migrants and resident species we are watching, birders of all ethnicities, races, and points of view are united in our shared passion for birds and together we will endure this pandemic. We must as there are more birds to be counted.

Neighborhood Nestwatch

Joshua Rose

Fig. 2. Eastern Phoebe with unique combination of colored bands. Photograph by Joshua Rose.

Covid-19 definitely wreaked havoc on birding during the spring of 2020: places were closed, or open but too crowded for comfort—not only birding hotspots but also bathrooms and food sources; greatly-multiplied household chores took time out of the day; trips, meetings, and activities were cancelled, along with virtually all out-of-town travel. This spring, I rarely left our neighborhood, and many days barely went outside. We live in a nice location, our yard is part of a large wooded area, but you can only get so many species in one habitat.

Birding in our yard does have one added dimension, though, one that I can't really get anywhere else. Several years ago, I volunteered our yard for the Smithsonian Neighborhood Nestwatch program. Every year from 2012 to 2019, Nestwatch sent someone to our yard to mist-net and band certain species, not only with the usual metal bands but also with colored plastic bands, a unique color combination on each individual of a species. In return, I've been keeping my eyes peeled for those color-banded birds and keeping a file of my sightings that I periodically send back to Nestwatch for inclusion in their data. My desk at home where I work just happens to have the best view of most of my birdfeeders, so more time at home has translated to more feeder watching, and lots of sightings of banded birds.

Before the Covid-19 shutdown began, I'd seen only two Nestwatch birds in 2020, a pair of Northern Cardinals. The male is our oldest and longest-surviving bird, banded in 2014. He's been through a few mates in that time; his partner of the past few years is a female banded in 2018. On April 7, about two weeks after most things closed, an Eastern Phoebe showed up, one that was banded last summer (Figure 2). Of four phoebes banded over the years, this was the first time I'd ever re-sighted one after it was banded. In May things got much busier because the catbirds returned. Not only are both of the catbirds that were banded last summer back this year, but three of the four that were banded in 2018 are back, too. Here is one random curveball: a Carolina Wren that was banded last summer appeared fairly regularly throughout the fall, through December 12, then disappeared—until May 27. Carolina Wrens visit my feeder pretty much year-round, and previously banded birds have stuck around through all seasons, so I figured that this one was gone for good. Surprise.

For more information about the Smithsonian's Neighborhood Nestwatch, go to https://nationalzoo.si.edu/migratory-birds/neighborhood-nestwatch.

The Outfall Pipe

Jay Shetterly

Fig. 3. Plaque on the Anderson Memorial Bridge, Cambridge. Photograph by Jay Shetterly.

For many years, the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority and the City of Cambridge have been working to replace the old combination sewer and stormwater systems that discharge combined sewer overflows into the Charles River. The project is not quite finished and on days when there is a light covering of ice on the river, there is open water near the outfall pipes.

There is an outfall pipe at the Weeks Footbridge. Birds seem to know this spot, including Common and Hooded mergansers, Black-crowned Night-Heron, and Great Blue Heron. On June 10, 2020, I saw a Northern Rough-winged Swallow here, a first for me in Cambridge. In the three-meter wide band of scrub lining the water's edge are pair after pair of Song Sparrows, rarely seen in the neighborhoods nearby.

If there is no bird of interest, one need only look upstream to the Anderson Memorial Bridge and imagine Quentin Compson of William Faulkner's The Sound and the Fury, despairing of himself and the South, jumping to his death. Devotees of Faulkner—like me—placed a small plaque there to mark Quentin's passing (Figure 3).

Bird-a-thoning During a Pandemic

Wayne R. Petersen

Mass Audubon's annual Bird-a-thon (BAT) was, for most participants this spring, a unique experience. The Covid-19 pandemic imposed significant changes in the overall BAT protocol this year, primary of which was encouraging birders to confine their birding activities pretty much to their yard or local areas within walking or bicycling distance of home. These constraints were aimed at complying with the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's and state-mandated social distancing and health guidelines, and at minimizing the carbon footprint of individual birders.

My own BAT experiences this year were remarkable in several ways. Having downsized to Linden Ponds (LP) in Hingham in February 2019, I am now residing in a retirement community comprising 1200–1300 mostly senior citizens. Accordingly, my living circumstances approached near lockdown conditions since March, a circumstance that also restricted my typical BAT activities. There was a silver lining to this situation, however. By confining my BAT birding only to the Linden Ponds community footprint and one short adjoining street, I was successfully able to locate 66 species between 6 pm on May 15 and 6 pm on May 16. This total exceeded my collective list of species seen since I moved to this retirement community over a year ago.

My solo birding adventures began Friday evening under propitious conditions involving warming 70-degree temperatures and light southwest winds. The forecast also called for rain during the night, with clearing conditions by morning. This combination provided some of the best mid-May birding conditions that one could hope for in Massachusetts. My early evening wildlife highlight was a brief look at a lovely gray fox, along with a resident Red-tailed Hawk, and a selection of some of the common local songbirds including Red-bellied Woodpecker, Great Crested Flycatcher, Fish Crow, Carolina Wren, House Finch, American Goldfinch, Chipping Sparrow, Baltimore Oriole, and Northern Cardinal. Not unhappy with some of my local resident species, I optimistically prepared for a more intense search in the morning, hoping the weather would deliver some welcome birding treasures.

At 6 am on Saturday, I was out on the 0.8-mile local nature trail poised for signs of newly arrived migrants, and I was not disappointed. A Veery quietly hopping on the trail in front of me was quickly followed by a Least Flycatcher and the liquid whit note of a Swainson's Thrush on the wooded hillside to my right. Three first LP birds for my list. Ecstatic and optimistic as I quietly birded along the trail, I soon added Ovenbird and Rose-breasted Grosbeak to my list. Exiting the gate at the end of the LP nature trail, I began birding the roadside trees and thickets on a short but quiet street running parallel to the LP complex. This is where the fun began. I quickly found another Veery and a couple more Swainson's Thrushes, and then heard singing Black-and-white, Nashville, Northern Parula, Chestnut-sided, Yellow-rumped, and Black-throated Green warblers. My dream for a decent migration was coming true.

As I continued to work the roadside trees and an adjacent swampy thicket during my quest for new species, I was practically mesmerized by every new species I recorded. Remember, this was not only more species than I'd ever recorded in my local patch, but it was also the first dedicated birding I'd been able to do in nearly two months. As the morning continued, other additions included a fly-by Solitary Sandpiper, Eastern Kingbird, Northern Rough-winged Swallow, Eastern Bluebird nesting in the LP community garden, a most unexpected Lincoln's Sparrow, and additional warblers including Common Yellowthroat, American Redstart, Magnolia, Bay-breasted, Black-throated Blue, Pine, and Wilson's. Even such long-distance migrants as Chimney Swift, Ruby-throated Hummingbird, and Barn Swallow made it on to my BAT roster.

I could not have been more thrilled to see even some of the common species, because each glimpse, and each song, provided renewed promise that even during a global pandemic, birds and bird migration live on to brighten our lives, if only we get outdoors to have a look. For this reason alone, BAT 2020 will forever be memorable in my mind, not just because of the terrific migration, but also because of the positive impact it made on me, given all the other dark events taking place in the world at the same time. Birds and birding rule!

Birding Plum Island in Peak Spring Migration during a Pandemic

Sean Williams

Fig. 4. The Goodno Woods crossing on the morning of May 11, 2020, with no people. Photograph by Sean Williams.

Parker River National Wildlife Refuge closed to motor vehicles on April 17, 2020, and remained closed throughout the duration of spring migration. However, pedestrians and bicyclists were permitted through the gates all the way down to Sandy Point State Reservation. This closure yielded a unique opportunity to bird the refuge road on foot during peak migration without disruption from motorized vehicles. Those who appreciate birding away from crowds on occasion may have reveled in the empty roads and eye-level Blackburnian Warblers along the S-curves. Goodno Woods on the morning of May 15 was eerily devoid of human life, despite the peak date and pleasant conditions (Figure 4). Below I describe some birding highlights at Plum Island in spring 2020 during the Covid-19 pandemic when many of normal societal operations were placed on hold.

Between April 26 and May 26, I visited the refuge five times, walked or biked 30 miles over 40 hours, and tallied 170 species. Typically, I arrived pre-dawn and departed around noon. On most days, I saw my first person around 8:00 am. April 26 was remarkably slow and non-speciose. Despite the late-April date and NEXRAD radar showing a pulse of migrants overnight, I tallied only one warbler, a Common Yellowthroat, beyond the expected Palm, Pine, and Yellow-rumped. Warblers were more diverse the following visit on May 3, totaling 11 species. While standing around the pines at The Wardens, I watched a flock of 22 ibises that flew north along the road, totally backlit by the sun. Given that flocks of ibis this size are unusual on the island, I photographed the flock on the off chance that not all of the ibises were Glossys. Indeed, upon returning home and brightening the images on the computer, one White-faced Ibis stuck out with its scarlet face with a thick white border. By May 11, peak warbler diversity hit 23 species, including an Orange-crowned and a "Western" Palm Warbler, both of which are more common in the fall migration than in spring.

On my final visit on May 26, the tail end of migration was characterized by many female or first-spring male warblers. Three Olive-sided Flycatchers were dotted along the S-curves south to the Bill Forward Blind. The main highlight that morning was seeing all six vireo species. Red-eyed Vireo is a given, but on that date even Blue-headed can be scarce. Warblings, which do not breed on Plum Island, are on territory by then. Regardless, both species were at Goodno Woods and Sandy Point. A Yellow-throated was singing at Goodno Woods, as was a White-eyed. Another White-eyed was singing south of the North Pool Overlook. Notably, these were the fourth and fifth White-eyed Vireos I'd detected on Plum this spring, which typically is a rare and sought-after migrant. Finally, a Philadelphia chided me in a tree across from Stage Island..

Although strenuous, the chance to bike and walk Plum Island without vehicular traffic during the pandemic was, I hope, a once-in-a-life-time occurrence. Fortunately, in early June the refuge reopened fully so that all can enjoy.

Pandemic Pileateds

Marsha C. Salett

Fig. 5. Pileated Woodpecker excavations are recent here, judging by the fresh wood chips around the base of the tree. Photograph by Marsha C. Salett.

It was New Year's Day and a Pileated Woodpecker was in my front yard extricating beetle grubs from the upper trunk of a tall oak—a FOY bird and a first sighting at my house. What an auspicious beginning to the year, I thought (although this is not the adjective I'd choose now to describe 2020). A week later, a Pileated flew over my next-door neighbor's house. When I returned home on February 1 from three weeks in Japan, I heard and saw a Pileated drumming on a tree next to my driveway.

A pair of Pileated Woodpeckers seems to nest annually, albeit in different locations, at Ridge Hill Reservation, Needham, the 352-acre conservation land that abuts my property. Breeding pairs stay on their territory all year and, according to Birds of the World, may retain the same territory for several years, averaging a distance of 0.53 kilometer (0.33 mile) between subsequent nesting sites (Bull and Jackson 2020). Would the Ridge Hill Pileateds nest near me in 2020?

Thanks to the pandemic, I was home to find out. Covid-19 kept me in Needham instead of traveling, and birding Ridge Hill instead of Mount Auburn during spring migration. I birded my patch almost every day and spent a lot of time looking out my windows. From March 1 through June 1, I saw one or both Pileated Woodpeckers 15 times within a half-mile radius of home: seven times around my house and eight times at Ridge Hill. Most years, I'm lucky to see or hear a Pileated two or three times. I also saw many signs of excavations and the telltale rectangular holes that they make (Figure 5).

My delight and fascination with the Pileated Woodpeckers grew with each encounter. On March 1, I looked out my kitchen window to see the male foraging on the ground on a dead tree that had fallen. All afternoon, he returned to the rotting log, staying for 10–20 minutes at a time. I never saw him there again.

I was surprised by how often the Pileateds foraged low, anywhere from the base of a tree to eye level. In the dull gray of the early spring forest, a crimson flash revealed the presence of a bird when it was quietly stripping bark or feeding on carpenter ants. On two occasions, a Pileated spiraled up a tree trunk like a huge—and more colorful—Brown Creeper, then flew away, fading into the dark conifers.

On April 16, I heard the pair duetting in my backyard and went outside to find them just before they flew across the trail in front of a mother and two children who were astonished by these large birds and the eye-popping contrast of their black and white wings. Stopped in their tracks, they asked me, "What are those birds?" As I walked back to the house, I could hear the kids still chattering about the Pileateds.

When the trees started to leaf out in May, Ridge Hill's red maple swamp was a magical place, glistening green in the sunlight of early morning. Eastern Towhees and Common Yellowthroats joined the bird chorus, which was soon punctuated by several Ovenbirds. Even they were no match for the raucous cuk-cuk-cuk-cuk-cuk-cuk-cuk duetting of the Pileateds that reverberated through the swamp. I heard them calling back and forth across the swamp a couple of times in May.

My most memorable encounter with a Pileated occurred on April 21, another bleak and raw spring day in New England. I was looking for a Brown Creeper nest under the bark of a dead white pine at the edge of the beaver swamp. The pine has been a favorite nesting tree for the creepers. This year, the first nest had been blown away in a storm a couple of days earlier and I wanted to see if they renested. I saw one of the creepers fly from the dead pine to an oak on the other side of the trail. The next moment, the male Pileated flew out of the forest and landed on a horizontal branch of the dead pine. Oblivious to me, he sat there and called repeatedly—no more than eight feet above my head. With every cuk, he opened his long stout bill only slightly and his throat quivered. I could see his face in exquisite detail: the blazing red crest and red cheek stripe, black stripe under the crest, the white stripe across his face and down his neck. What a handsome bird.

The Brown Creeper flew back to the pine and scuttled up the trunk: tiny, cryptic, inconspicuous. The Pileated Woodpecker called from his perch: large, flashy, loud. Two species, so different, each so cool in its own way. My spirits rose, transcending the weather, transcending the pandemic.

Reference

- Bull, E. L. and J. A. Jackson. (2020). Pileated Woodpecker (Dryocopus pileatus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.pilwoo.01