Duncan S. Evered

Although Plymouth Beach does not enjoy a reputation as a "hotspot" for rare birds, increased coverage by field observers in recent years has produced an impressive list of rarities at all seasons. Plymouth Beach may well be the sleeper of the Massachusetts coast.

Although Plymouth Beach does not enjoy a reputation as a "hotspot" for rare birds, increased coverage by field observers in recent years has produced an impressive list of rarities at all seasons. Plymouth Beach may well be the sleeper of the Massachusetts coast.

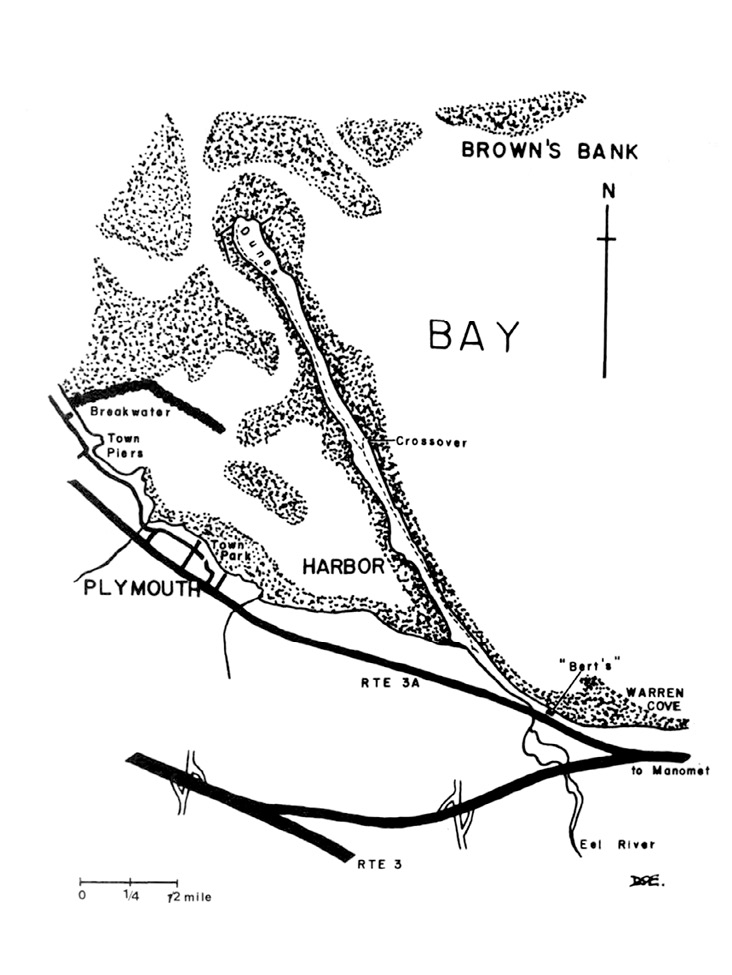

Bruce Sorrie wrote the above in summary to an article that appeared twelve years ago in Bird Observer, volume 1, May-June 1973. Evidently, for many Massachusetts birders the location of Plymouth Beach (between the Cape and Plum Island, but not close enough to either) and the logistics of getting out there and back (walk six miles or use an off-road vehicle) still prove too much of an effort. Consequently, Plymouth Beach still does not enjoy the recognition it surely deserves. The purpose of this article is to show that Plymouth Beach "sleeps" no more: since Bruce's prophecy, over fifty additional species have been documented. First, as a testimony to this area's pedigree, I present a fully researched list of the 243 species reliably recorded from 1945 to 1984 in the area defined in the accompanying figure. A detailed annotation then follows, offering any birder who wishes to discover Plymouth Beach the advantage of better knowing where and when to look. In a broader ecological perspective, leaving rarities like Burrowing Owl and Sharp-tailed Sandpiper aside, Plymouth Beach is of major importance to literally tens of thousands of wintering waterfowl and migratory shorebirds, over a thousand nesting terns, and a valuable few struggling pairs of Piping Plover. How long Plymouth Beach will maintain such an impressive concentration and diversity of avian forms will depend on the amount of future interest taken in this exciting place.

THE SPECIES LIST

In order to fully understand this bird list, it is necessary to explain some of the arbitrary conventions used in its compilation. Average abundance during the season when the species is most frequent is indicated as follows: C = common (should be seen), U = uncommon (might be seen), R = rare (worth looking for), and V = very rare or vagrant (recorded on one or two occasions, i.e., apparently exceptional). These four simplified categories are used to convey the chances of a species being seen in ideal conditions by a knowledgeable observer. Therefore, the abundance rank selected for each species not only depends on its average numerical abundance, but also on its conspicuousness and the awareness of the observer. Seasonal occurrence is indicated as follows: S = summer, M = migration, and W = winter. A capitalized symbol marks the season of most frequent occurrence (to which the above abundance ranking—C, U, R, or V—refers), and a lowercase symbol indicates a lesser occurrence. The migration period of each species occurring on Plymouth Beach is typical of other southshore locations, and an asterisk denotes proven breeding on Plymouth Beach.

| Species |

Status |

Seasonal Abundance |

|

Species |

Status |

Seasonal Abundance |

| Red-throated Loon |

C |

Mw |

|

Ruddy Duck |

V |

W |

| Arctic Loon |

V |

M |

|

Turkey Vulture |

V |

M |

| Common Loon |

C |

Mw |

|

Osprey |

U |

M |

| Pied-billed Grebe |

R |

mW |

|

Amer. Swallow-tailed Kite |

V |

M |

| Horned Grebe |

C |

Mw |

|

Bald Eagle |

R |

sMw |

| Red-necked Grebe |

U |

mW |

|

Northern Harrier |

U |

Mw |

| Western Grebe |

V |

W |

|

Sharp-shinned Hawk |

R |

Mw |

| Northern Fulmar |

R |

M |

|

Red-shouldered Hawk |

R |

Mw |

| Cory's Shearwater |

R |

M |

|

Red-tailed Hawk |

R |

mW |

| Greater Shearwater |

R |

sM |

|

Rough-legged Hawk |

R |

W |

| Sooty Shearwater |

R |

M |

|

American Kestrel* |

C |

sMw |

| Manx Shearwater |

V |

S |

|

Merlin |

U |

Mw |

| Wilson's Storm-Petrel |

U |

Sm |

|

Peregrine Falcon |

U |

M |

| Leach's Storm-Petrel |

V |

M |

|

Gyrfalcon |

V |

M |

| Northern Gannet |

U |

sMw |

|

Northern Bobwhite |

R |

W |

| Great Cormorant |

C |

smW |

|

Clapper Rail |

R |

sMw |

| Double-crested Cormorant |

C |

sMw |

|

King Rail |

V |

M |

| American Bittern |

R |

M |

|

Virginia Rail |

U |

mW |

| Least Bittern |

R |

M |

|

Sora |

U |

M |

| Great Blue Heron |

U |

sMw |

|

American Coot |

R |

W |

| Great Egret |

U |

Sm |

|

Sm Sandhill Crane |

V |

M |

| Snowy Egret |

C |

Sm |

|

Black-bellied Plover |

C |

Mw |

| Little Blue Heron |

U |

Sm |

|

Lesser Golden-Plover |

U |

M |

| Tricolored Heron |

R |

Sm |

|

Wilson's Plover |

R |

M |

| Cattle Egret |

R |

S |

|

Semipalmated Plover |

C |

M |

| Green-backed Heron |

R |

sM |

|

Piping Plover* |

U |

Sm |

| Black-crowned Night-Heron |

C |

Smw |

|

Killdeer* |

C |

sMw |

| Yellow-crowned Night-Heron |

R |

Sm |

|

American Oystercatcher |

R |

Sm |

| Glossy Ibis |

U |

Sm |

|

American Avocet |

V |

M |

| Mute Swan |

C |

smW |

|

Greater Yellowlegs |

C |

M |

| Snow Goose |

R |

Mw |

|

Lesser Yellowlegs |

U |

M |

| Brant |

C |

Mw |

|

Solitary Sandpiper |

R |

M |

| Canada Goose |

C |

Mw |

|

Willet |

U |

M |

| Wood Duck |

R |

M |

|

Spotted Sandpiper* |

C |

Sm |

| Green-winged Teal |

U |

Mw |

|

Upland Sandpiper |

R |

M |

| American Black Duck |

C |

mW |

|

Whimbrel |

U |

M |

| Mallard |

C |

Mw |

|

Hudsonian Godwit |

R |

M |

| Northern Pintail |

R |

Mw |

|

Marbled Godwit |

V |

M |

| Blue-winged Teal |

U |

M |

|

Ruddy Turnstone |

C |

Mw |

| Gadwall |

R |

Mw |

|

Red Knot |

C |

Mw |

| Eurasian Wigeon |

V |

mW |

|

Sanderling |

C |

Mw |

| American Wigeon |

U |

mW |

|

Semipalmated Sandpiper |

C |

M |

| Canvasback |

R |

W |

|

Western Sandpiper |

U |

M |

| Redhead |

R |

W |

|

Least Sandpiper |

C |

M |

| Ring-necked Duck |

R |

w |

|

White-rumped Sandpiper |

U |

M |

| Greater Scaup |

U |

Mw |

|

Baird's Sandpiper |

R |

M |

| Lesser Scaup |

R |

W |

|

Pectoral Sandpiper |

C |

M |

| Common Eider |

C |

mW |

|

Sharp-tailed Sandpiper |

V |

M |

| King Eider |

R |

W |

|

Purple Sandpiper |

R |

Mw |

| Harlequin Duck |

V |

w |

|

Dunlin |

C |

Mw |

| Oldsquaw |

C |

Mw |

|

Curlew Sandpiper |

R |

M |

| Black Scoter |

U |

Mw |

|

Stilt Sandpiper |

R |

M |

| Surf Scoter |

C |

Mw |

|

Buff-breasted Sandpiper |

R |

M |

| White-winged Scoter |

C |

Mw |

|

Ruff |

R |

M |

| Common Goldeneye |

C |

mW |

|

Short-billed Dowitcher |

C |

M |

| Barrow's Goldeneye |

R |

W |

|

Long-billed Dowitcher |

R |

M |

| Bufflehead |

C |

mW |

|

Common Snipe |

U |

Mw |

| Hooded Merganser |

R |

mW |

|

American Woodcock |

V |

M |

| Common Merganser |

R |

mW |

|

Wilson's Phalarope |

R |

M |

| Red-breasted Merganser |

C |

Mw |

|

Red-Necked Phalarope |

U |

M |

| Red Phalarope |

R |

M |

|

Black-capped Chickadee |

U |

Mw |

| Pomarine Jaeger |

V |

M |

|

Tufted Titmouse |

U |

mW |

| Parasitic Jaeger |

R |

M |

|

Marsh Wren |

U |

sMw |

| Great Skua |

V |

M |

|

Golden-crowned Kinglet |

R |

M |

| Laughing Gull |

C |

sM |

|

Ruby-crowned Kinglet |

U |

M |

| Little Gull |

R |

M |

|

Northern Wheatear |

V |

M |

| Common Black-headed Gull |

R |

sMw |

|

Swainson's Thrush |

R |

M |

| Bonaparte's Gull |

C |

Mw |

|

American Robin |

U |

sM |

| Mew Gull |

V |

W |

|

Gray Catbird |

U |

Mw |

| Ring-billed Gull |

C |

sMw |

|

Northern Mockingbird |

C |

sMw |

| Herring Gull |

C |

sMw |

|

Water Pipit |

C |

Mw |

| Iceland Gull |

R |

mW |

|

Cedar Waxwing |

R |

Mw |

| Lesser Black-backed Gull |

R |

Mw |

|

European Starling* |

C |

sMw |

| Glaucous Gull |

V |

W |

|

Philadelphia Vireo |

V |

M |

| Great Black-backed Gull |

C |

sMw |

|

Red-eyed Vireo |

R |

M |

| Black-legged Kittiwake |

U |

Mw |

|

Golden-winged Warbler |

V |

M |

| Sabine's Gull |

V |

M |

|

Tennessee Warbler |

R |

M |

| Gull-billed Tern |

V |

M |

|

Nashville Warbler |

R |

M |

| Caspian Tern |

U |

M |

|

Yellow Warbler |

U |

M |

| Royal Tern |

R |

Sm |

|

Magnolia Warbler |

R |

M |

| Sandwich Tern |

R |

M |

|

Yellow-rumped Warbler |

C |

Mw |

| Roseate Tern* |

C |

sM |

|

Black-throated Green Warb. |

R |

M |

| Common Tern* |

C |

Sm |

|

Palm Warbler |

U |

M |

| Arctic Tern* |

C |

S |

|

Bay-breasted Warbler |

R |

M |

| Forster's Tern |

U |

M |

|

Blackpoll Warbler |

U |

M |

| Least Tern* |

C |

Sm |

|

American Redstart |

R |

M |

| Sooty Tern |

V |

M |

|

Northern Waterthrush |

R |

M |

| Black Tern |

U |

M |

|

Connecticut Warbler |

V |

M |

| Black Skimmer |

U |

Sm |

|

Common Yellowthroat |

U |

M |

| Dovekie |

R |

Mw |

|

Wilson's Warbler |

R |

M |

| Thick-billed Murre |

R |

W |

|

Northern Cardinal |

U |

smW |

| Razorbill |

R |

W |

|

Rose-breasted Grosbeak |

V |

M |

| Rock Dove |

C |

Smw |

|

Dickcissel |

V |

M |

| Mourning Dove |

C |

sMw |

|

Rufous-sided Towhee |

R |

Mw |

| Black-billed Cuckoo |

V |

M |

|

American Tree Sparrow |

U |

Mw |

| Great Homed Owl |

R |

S |

|

Chipping Sparrow |

R |

M |

| Snowy Owl |

R |

Mw |

|

Field Sparrow |

R |

M |

| Burrowing Owl |

V |

M |

|

Savannah Sparrow |

C |

sMw |

| Short-eared Owl |

U |

Mw |

|

"Ipswich" Sparrow |

C |

mW |

| Common Nighthawk |

R |

M |

|

Sharp-tailed Sparrow* |

U |

sMw |

| Whip-poor-will |

V |

M |

|

Seaside Sparrow |

R |

Mw |

| Chimney Swift |

U |

Sm |

|

Song Sparrow* |

C |

sMw |

| Ruby-throated Hummingbird |

V |

M |

|

Lincoln's Sparrow |

R |

M |

| Belted Kingfisher |

U |

sMw |

|

Swamp Sparrow |

U |

Mw |

| Yellow-bellied Sapsucker |

R |

M |

|

White-throated Sparrow |

U |

Mw |

| Downy Woodpecker |

U |

smW |

|

White-crowned Sparrow |

R |

M |

| Northern Flicker |

U |

Mw |

|

Dark-eyed Junco |

U |

Mw |

| Yellow-bellied Flycatcher |

V |

M |

|

Lapland Longspur |

C |

Mw |

| Acadian Flycatcher |

V |

M |

|

Snow Bunting |

C |

mW |

| "Traill's" Flycatcher |

R |

M |

|

Bobolink |

R |

M |

| Western Kingbird |

V |

M |

|

Red-winged Blackbird |

C |

sMw |

| Eastern Kingbird |

R |

M |

|

Eastern Meadowlark |

R |

mW |

| Horned Lark* |

C |

sMw |

|

Rusty Blackbird |

R |

M |

| Purple Martin |

R |

M |

|

Common Grackle |

C |

M |

| Tree Swallow* |

C |

sMNo. |

|

Brown-headed Cowbird |

U |

M |

| Rough-winged Swallow |

U |

sM |

|

Northern Oriole |

R |

M |

| Bank Swallow |

U |

sM |

|

House Finch |

C |

sMw |

| Cliff Swallow |

V |

M |

|

Common Redpoll |

R |

W |

| Barn Swallow |

C |

sM |

|

Pine Siskin |

R |

W |

| Blue Jay |

U |

sMw |

|

American Goldfinch |

U |

sMw |

| American Crow |

C |

sMw |

|

House Sparrow |

C |

Smw |

| Fish Crow |

R |

Mw |

|

|

|

|

A Birding Guide to Plymouth Beach and Evirons

I again take the liberty of quoting Bruce Sorrie almost verbatim, this time for his description of the logistics of birding Plymouth Beach. The best way to get to the beach is to drive south on Route 3 and take the exit marked "Plimoth Plantation - Manomet." Continue east about a mile and take a sharp left turn onto Route 3A toward Plymouth. Proceed north about one mile to Bert's Restaurant on the right, immediately north of which is the beach parking lot and road. In the summer (Memorial Day to school opening) unless your car has a "Town of Plymouth Facilities" sticker, you will have to pay for parking here. Plan to walk the beach and to set out at low tide (ideally at dawn for land birds at the base of the beach) so that when you reach the tip of the beach, the tide is high for the best viewing of shorebirds and waterfowl.

"Plymouth Beach" refers to the beach north of the parking lot at Bert's Restaurant and includes only the waters and flats visible from the beach itself, which broadly encompasses the harbor and part of Plymouth Bay.

I again take the liberty of quoting Bruce Sorrie almost verbatim, this time for his description of the logistics of birding Plymouth Beach. The best way to get to the beach is to drive south on Route 3 and take the exit marked "Plimoth Plantation - Manomet." Continue east about a mile and take a sharp left turn onto Route 3A toward Plymouth. Proceed north about one mile to Bert's Restaurant on the right, immediately north of which is the beach parking lot and road. In the summer (Memorial Day to school opening) unless your car has a "Town of Plymouth Facilities" sticker, you will have to pay for parking here. Plan to walk the beach and to set out at low tide (ideally at dawn for land birds at the base of the beach) so that when you reach the tip of the beach, the tide is high for the best viewing of shorebirds and waterfowl.

The height above the beach together with the protection provided by the seawall makes the parking lot next to Bert's the most comfortable and convenient place to scan for loons, grebes, and pelagics. During strong nor'easters, loons and grebes often shelter in Warren Cove, and a walk south along the seawall is then advisable; otherwise they occur along the whole length of the bayside beach. October, from midmonth on, produces both the quantity, e.g., maxima of 80 Horned Grebes and 80 Red-throated and Common loons, and the quality, e.g., three species of loon together (see Field Records of October 1984 in BOEM, 13: 27). Typically only a dozen or so Horned Grebes and Common Loons stay the whole winter, the Red-throats normally leaving in January. During severe storms, on account of the waves that tumble over the seawall making serious seawatching quite futile, it is usually best to go to Manomet Point, returning to the beach after the high winds have diminished somewhat. During such revisits, the outer beach, especially the tip, has produced resting and outward-bound "goodies" like Sabine's Gull, Sooty Tern (after Hurricane David), Leach's Storm-Petrel, and Pomarine Jaeger. Late summer and early fall most predictably produce (in order of frequency): Northern Gannet, Wilson's Storm-Petrel, Parasitic Jaeger, Red-necked Phalarope, and the large shearwaters. Late fall storms produce more gannets. Blacklegged Kittiwake, the odd Northern Fulmar, and the exceptional Great Skua. Less is known of spring storms, but both phalarope species occur fairly regularly.

The large heronry on Clark's Island , which lies two miles northeast of the beach, is the source of the wealth of waders that pace and stab in the harbor lagoons and channels throughout the summer. Low tide is the time to see good numbers of Snowy Egrets (up to 150 in late summer) and, possibly, Little Blue Heron and Great Egret. The mouth of the Eel River is a good place for close views when tides are intermediate , but the sun tends to produce severe glare here except in early mornings or on overcast days. Because of this, the best viewing sites are from points looking west from the harbor shore. Unfortunately, many roads leading to good vantage points are private, and unless specific permission has been granted in advance, birders should not use them. Those shown in the figure are accessible and worthy of a visit. During both spring and fall migrations, the numbers of waders decrease, but the rarer species occur with greater frequency. The less common waders, such as Cattle Egret and Glossy Ibis, are best seen from the tip of the beach winging their way to (evening) or from (morning) Clark's Island and their feeding grounds.

The established reputation of Plymouth Beach and Harbor as a site for abundant winter waterfowl results in their status being comparatively well known. Brant have increased dramatically over the last decade. The wintering population is now over 1500; swelled with migrants in April and November, the total can exceed 5000. At high tide, truly impressive flocks gather on and around the sand flats at the tip of the beach, affording close study. However, they are easily disturbed; so approach with caution. At low tide the Brant join the eider as blurry dots on the expanses of sand and mussel flats—frustrating to the birder but an apt reminder of the abundant resources Plymouth Harbor offers to waterfowl. Of the ducks, small numbers (maximum of five) of Barrow's Goldeneye and the odd King Eider are the reliable attractions for the birder searching for the unusual. The Barrow's are best viewed from the Breakwater and Town piers at high tides from early December through March. The Kings may be with any of the 15,000 of more Common Eider that frequent the whole estuary. But despair not at the odds, for the Kings that are found tend to stay in the same flock and at the same general location for several weeks at a time. If you fancy streams of eider flying across a glowing sunset, try the tip of Plymouth Beach toward dusk. Mornings produce better, if somewhat less dramatic, lighting, but the spectacle is more likely to be tarnished by sportsmen. Concentrations of other sea and bay ducks in winter are generally modest, occasionally good, with scoter, Bufflehead, Common Goldeneye, Red-breasted Merganser and Oldsquaw dominating. Larger flocks can be seen in the distance from the parking lot during heavy migrations in October and November, but few depart from their course (Saquish Head in Duxbury to Manomet Point) and come to rest in the bay. The rarer puddle ducks occur briefly and sporadically during heavy migration and after the first major freeze-ups in December. The latter is also a time when the rare bay ducks (and American Coot) occasionally occur.

The only raptor nearly omnipresent on Plymouth Beach is the American Kestrel, one or more being seen almost without exception throughout the year. From September through October and into early November, either a Merlin or a Peregrine Falcon can be expected on all but the briefest, or unluckiest, of trips. Often the birds are seen hunting, but on a good number of occasions, especially in the late mornings, the birds are actively migrating. Twice in the last two years, Gyrfalcons have been seen racing along the beach in late fall. August and September are the times to watch for Ospreys fishing over the harbor or the pond across the road from Bert's. (This pond is always worth checking for feeding and resting ducks, gulls and terns, and a large icterid/swallow roost, with the best view from the height of the Pilgrim Sands Motel parking lot next to Bert's Restaurant.) Northern Harriers regularly quarter the harborside salt marshes and dunes in late fall and winter, routinely including Duxbury Beach across the bay to the north on their patrols. All other hawks prove very scarce in migration and irregular in winter. In recent summers and early falls, the Bald Eagle has become more regular.

Flood tides in fall are the best times to search for the ever elusive, but far from impossible, rails. Although the salt marshes on the west side of the harbor are still good despite some filling in, permission is essential to gain access to walk them. Therefore, the mouth of the Eel River at the base of Plymouth Beach, especially around the large clump of reeds, is the site recommended. (Just after leaving the parking lot, a footpath leads from the track down a wash to the river and then follows it to the reed bed.) Sora is the most common, but Virginia and Clapper rails are often seen too and occasionally "jump up" for the Christmas Bird Count. Although not confirmed, it is possible that Clapper Rail surreptitiously breeds here. Walking this area in fall, or even winter, may also produce Sharp-tailed Sparrow, which nests in some years, and occasionally a Seaside. After nesting in the marshes surrounding the pond across from Bert's, a Marsh Wren or two might be found among the reeds, often lingering into early winter.

The huge expanses of sand and mud flats and mussel beds of Plymouth Harbor provide a tremendous amount of invertebrate food for shorebirds. Plymouth Beach provides the other essential component of a stopover site, a place for the birds to rest at high tide, making it one of the top ten "fueling" sites on the whole North American Atlantic coast according to the International Shorebird Survey. Intensive shorebird censusing over the last thirteen years by Manomet Bird Observatory staff has produced the following average peak fall migration numbers for the most common roosting species: Semipalmated Sandpiper (5000), Sanderling (1000), Dunlin (800), Black-bellied Plover (650), Semipalmated Plover (500), and Ruddy Turnstone (150). Red Knot and Short-billed Dowitchers now use the beach much less than they used to because of increasing human disturbance. Nevertheless, flocks of up to a thousand and more of both species still feed on the flats and sporadically visit the beach. Thus, despite human and vehicular activity, Plymouth Beach still boasts a great variety of shorebirds. Early October days routinely produce eighteen or nineteen species, and rarities are uncannily frequent, the most notable being the first Massachusetts record of Sharp-tailed Sandpiper (1971) and the regularity with which Wilson's Plover occurs in the shingle and gravelly areas at the tip of the beach in the latter part of April, May, and early June.

A falling tide is the best time to observe the shorebirds at their most dynamic, as they start feeding in the freshly created tidal pools adjacent to roosting sites before moving off to the emerging flats. In the early fall, roosts occur on the shingle stretches and the raised saltmarsh along the harbor side of the beach, and these can be viewed without causing disturbance from several points along the beach road. On the rainier and cooler days of September and through the winter, in the absence of frequent human harassment, shorebirds (mainly Sanderling and Dunlin) are able to establish a regular roost on the comparatively deserted sandy beaches along the bay side and at the tip of the beach.

From late August through October, large gulls start to roost in substantial numbers (routinely a thousand birds and up to ten thousand associated with major fish kills) on the sand flats around the tip of the beach and on the bay side north of the crossover. In recent years Lesser Black-backed Gulls have proved to be regular in small numbers from August to October: four individuals in 1982 and at least five in 1984. (I'm sure nobody looked hard enough in 1983!) Although the size of these gull assemblages declines sharply in late October, gulls often rest on the beach in appreciable numbers during and immediately after storms in late fall and early winter. At such times, careful scrutiny occasionally yields an early Iceland, later perhaps a Glaucous or lingering Lesser Black-backed Gull. In winter, several hundred very approachable Ring-billed Gulls loaf around the Breakwater parking lot behind McGrath's Restaurant at high tide and on a receding tide are found in the saltmarshes farther north. (Take a right from McGrath's and after two hundred yards another right as the road bears sharply left.) In early spring when numbers are swelled with northbound migrants, these flocks are worth checking carefully for Mew Gull (of the European race), which has occurred twice. The gulls in late spring and summer are much less numerous, but scanning along the sand flats has produced various larid oddities. A juvenile Common Black-headed Gull in July of 1984 and late spring Iceland Gulls take pride of place, ahead of several summer "white winged" gulls, one of which was probably an albinistic or leucistic bird.

From early May until early August, the dunes at the tip of Plymouth Beach host one of the most important terneries within the Cape Cod "super-colony," both in terms of numbers (1114 pairs of Common Terns bred in1984) and diversity (four species invariably breed). The colony in the past has suffered declines due to rat predation and natural food shortage, but now neither is significant. There is every reason to believe that with continued monitoring to control human disturbance, Plymouth Beach might assume its former significance (i.e., 7500 pairs in 1954). Indeed, the Plymouth colony is presently expanding, most likely through absorbing birds from the declining colony on Monomoy. Least Terns nest every year in small numbers (15-45 pairs) and in various parts of the beach depending on the location of an undisturbed pebbly substrate and the extent of the high spring tides. Arctic Terns have shown a recent decline, perhaps reflecting climatic change more than anything else as this species is on the southernmost edge of its range. Nevertheless, in 1984, the typical 40 percent of the total Massachusetts population was nesting in the low, mobile dunes and pebbly edges of the Plymouth Beach colony. Roseate Terns nest in variable, but usually small, numbers (5-50 pairs) in the densely vegetated dune "hollows" in the midst of the colony.

Large numbers of terns may be found resting around the northwest jetty at high tide, and in late July and early August very impressive flocks of terns may occur on the sand flats with up to 2000 Common Terns and 800Roseates. At night roosts may number even more. These birds are mostly adults and probably originate from colonies in southern New England, dispersing north after breeding to fish the productive coastal waters around Cape Cod. At this time, and to a lesser extent in the spring, the rarer "southern" terns occur on the extensive bayside sand flats with surprising regularity, examples being Forster's, Royal, Sandwich, and Gull-billed terns, as well as Black Skimmer, which formerly bred sporadically. At such times, as many as seven species of tern may be seen on Plymouth Beach in a single day.

Snowy Owls, although rare, are well worth scanning the dunes for during the day or the salt marshes in the twilight hours, where they hunt shorebirds. The best times are in November and December and again in March and April when migrants pause a few days. The Short-eared Owl seems to have a strategy similar to its diurnal counterpart, the Northern Harrier, in that it regularly commutes between Plymouth and Duxbury beaches, often in response to disturbance. Although they are not a serious problem to the nesting terns, Great Horned Owls occasionally make hunting forays onto the beach from their surrounding suburban homes.

A cursory glance at the bird list reveals that land birds are rather poorly documented. In part, this is a reflection of Plymouth Beach not being a particularly good land trap for migrants due to its geographical position and the relative paucity of dense (and diverse) vegetative cover. But in some part, it simply reflects the fact that in the past birders have not scrutinized the bushes thoroughly enough. Migrant land birds may be quite numerous in the early morning before, having worked their way south to the base of the beach, they are lost in the relative wealth of cover found on the mainland. The bird list clearly hints at the virtues of giving the loose thickets of saltspray rose and beach plum a "spish" or two—for a Dickcissel, a Golden-winged, or a Connecticut warbler! The weedy patches of goldenrod and dusty miller regularly hold good numbers of Savannah Sparrows and Palm Warblers, so why not the odd Lark or Clay-colored sparrow? This is not to suggest that Plymouth Beach cannot offer anything of interest but the accidental Northern Wheatear or incidental Western Kingbird. The beach provides food and shelter on a regular basis for a number of interesting land birds. Two or more pairs of Horned Larks breed each year north of the crossover. From mid-September on, Water Pipits are regular in their occurrence, with numbers occasionally exceeding fifty. The last days of September may produce early Lapland Longspurs in the dunes and along the harborside at low tide, with up to sixty in late October and November. Soon after the longspurs, the Snow Buntings arrive. But it is not until December that the dunes and bayside upper beach regularly have roving flocks of several hundred or more. Another attraction of the latter habitat is the presence of "Ipswich" Sparrows from mid-October to April, with as many as fourteen seen in one day.

As with all brief birding accounts, this is a fragmentary abstract of a location's avifauna. However, it is hoped that it will give the flavor of Plymouth Beach and illustrate its importance as a feeding, resting, and nesting place for birds - and, by encouraging a greater awareness of Plymouth Beach's value to our wildlife, create a stronger concern for its healthy persistence. I thank all MBO staff and interns, past and present, whose notebooks and knowledge have been such an important source of information in the writing of this account. The bird list is a complete revision of one prepared by Bruce A. Sorrie and Paul K. Donahue in 1975. Without their groundwork, and the critical assistance of Lyla R. Messick, the task of its compilation would have been more daunting. For help with specific enquiries and comments on drafts (+), I gratefully thank David E. Clapp, Trevor L. Lloyd-Evans (+), Brian A. Harrington (+), Lyla R. Messick (+), Wayne R. Petersen, P. William Smith, Bruce A. Sorrie, and Peter Trull.

Duncan S. Evered, a visitor from England whose paper, "Pacific (and Arctic) Loon Identification," appeared in the February 1985 issue of Bird Observer, completed the work reported here during several periods of residence at Manomet Bird Observatory since 1982. Duncan has now transferred his research efforts to the Long Point Bird Observatory in Ontario, Canada.