David McLain

Call it the flooding sanctuary. Bisected by the Mill River as it flows into the 1840 Oxbow of the Connecticut River, much of the land is inundated when April showers bring…April floods. Or March floods. Or May floods, sometimes lingering into June. Or October floods. Nearly everything was under water, and the meadows were navigable by motorboat in the aftermath of Hurricane Irene in late August 2011. The variable floods create variable conditions that favor a variable avifauna from year to year and season to season. Coupled with the wide variety of habitats and strategic location on the landscape, Mass Audubon's Arcadia Wildlife Sanctuary is one of the best birding destinations in Western Massachusetts, and the best in the state according to Yankee Magazine (Yankee Magazine Editors 2015).

Call it the flooding sanctuary. Bisected by the Mill River as it flows into the 1840 Oxbow of the Connecticut River, much of the land is inundated when April showers bring…April floods. Or March floods. Or May floods, sometimes lingering into June. Or October floods. Nearly everything was under water, and the meadows were navigable by motorboat in the aftermath of Hurricane Irene in late August 2011. The variable floods create variable conditions that favor a variable avifauna from year to year and season to season. Coupled with the wide variety of habitats and strategic location on the landscape, Mass Audubon's Arcadia Wildlife Sanctuary is one of the best birding destinations in Western Massachusetts, and the best in the state according to Yankee Magazine (Yankee Magazine Editors 2015).

Adding to the mystique, the sanctuary is located on a major flyway along the Connecticut River. The Silvio O. Conte National Wildlife Refuge conducted a three-year migratory bird stopover habitat survey and found significantly more birds migrating along the big river than farther away (Litwin and Lloyd-Evans 2006). Raptors and other migrants also follow the nearby Mount Holyoke (east-west) and Mount Tom (north-south) ranges. Another productive area nearby is the East Meadows of Northampton, with vast fields of agriculture.

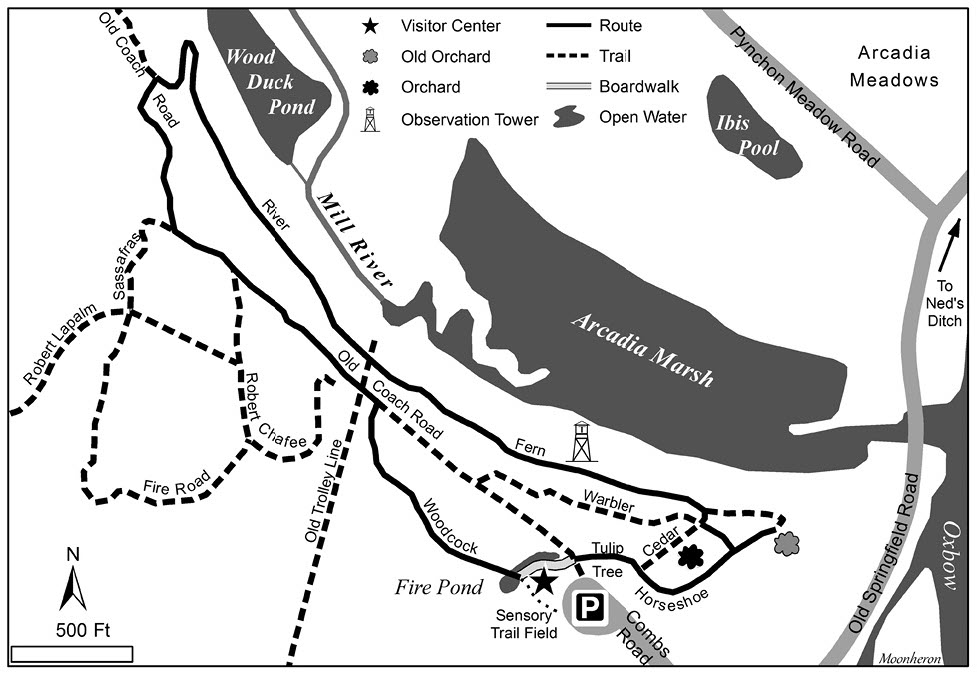

Map of Arcadia

The rich diversity of habitats provides an oasis for birds on the sanctuary, tucked between urban Northampton and Easthampton. The predominant feature of Arcadia, not readily apparent to most visitors, is an older Connecticut River oxbow that was cut off from the main stem some 800 years ago. The basin of the old oxbow is well vegetated with swamp forest, buttonbush marsh, open mats of sparganium and smartweed, and scattered ponds with spatterdock and coontail. A section of this oxbow is known as Ned's Ditch. Another section has been impounded by beavers and is mainly an open buttonbush marsh. The slow and meandering, sandy-bottomed Mill River, with its exemplary floodplain forest of silver maple, pin oak, and green ash canopy above a dense fern ground cover, flows through half of the old oxbow before reaching the 1840 Oxbow. The channel of a historic Mill River diversion and its floodplain forest are adjacent to Ned's Ditch. Within the arc of the old oxbow is Arcadia Meadows, with a suite of early successional habitat and organic agricultural fields, parts of which are owned by the city of Northampton and managed by Arcadia.

The remainder of the sanctuary comprises oak, maple, pine, and hemlock forest; forested wetlands perched on an impervious bed of glacial Lake Hitchcock clay—a rare community in Massachusetts called Black Gum-Pin Oak-Swamp White Oak Perched Swamp— a beaver pond that was formerly a sphagnum bog until, well, beavers; 31 vernal pools; two small woodland streams; and the disturbed habitat around the buildings and orchard area. The eastern boundary abuts the oxbow of the Connecticut River and a stream-capture remnant known as Danks Pond. One of the woodland streams, Hemlock Brook, has been diverted several times in its history and now flows into the Manhan River, rather than the Mill River, making Arcadia part of two watersheds. One of the relic beds of Hemlock Brook forms the vernal pool and dug-out Fire Pond behind the Visitor Center.

|

M - migrant nonbreeder

|

76

|

|

N - nonbreeder (winter resident, or summer visitor)

|

62

|

|

B - breeding on the sanctuary

|

95

|

|

V - vagrant, out of range stray, coastal migrant

|

36

|

| |

269

|

Table 1. Status of 269 bird species recorded at Arcadia Wildlife Sanctuary.

No fewer than 269 bird species have made an appearance at Arcadia, 95 of which have bred there (Table 1). The rest are either migrants passing through to breeding grounds farther north and wintering grounds farther south, such as Snow Goose, Swainson's Thrush, and Cape May Warbler; fall and winter visitors returning from their northerly breeding grounds, such as Northern Shrike, Snow Bunting, and Golden-crowned Kinglet; postbreeding southern species dispersing northward, such as Great Egret; or to birders' delight, rare vagrants straying from their normal migration routes (Table 2). Still others are local breeders that use Arcadia's habitats within their territories but nest elsewhere, including Peregrine Falcon and Belted Kingfisher.

Rarities are what draw birders like bees on honey. Arcadia boasts a list of 36 vagrants (Table 2), mainly strays from coastal flyways, western migrants off course, or southern overshoots. Most have been one-time wonders but Cackling Goose, Clay-colored Sparrow, Blue Grosbeak, and Dickcissel have become almost regular attractions. More species will surely be added in the future. Arcadia Meadows, Arcadia Marsh, Ned's Ditch, the Orchard, and the Oxbow have been the best spots for rarities. Spring and fall are the best times, but good birding can be had year-round.

|

Greater White-fronted Goose

|

Glaucous Gull

|

Le Conte's Sparrow

|

|

Ross's Goose

|

Common Tern

|

Nelson's Sparrow

|

|

Cackling Goose

|

American White Pelican

|

Harris's Sparrow

|

|

Tundra Swan

|

Great Cormorant

|

Yellow-breasted Chat

|

|

Ruddy Turnstone

|

Glossy Ibis

|

Yellow-headed Blackbird

|

|

Sanderling

|

Say's Phoebe

|

Yellow-throated Warbler

|

|

Wilson's Phalarope

|

Western Kingbird

|

Prothonotary Warbler

|

|

Red-necked Phalarope

|

White-eyed Vireo

|

Hooded Warbler

|

|

Laughing Gull

|

Northern Wheatear

|

Summer Tanager

|

|

Black-headed Gull

|

Bohemian Waxwing

|

Western Tanager

|

|

Iceland Gull

|

Clay-colored Sparrow

|

Blue Grosbeak

|

|

Lesser Black-backed Gull

|

Lark Sparrow

|

Dickcissel

|

Table 2. Vagrant species recorded at Arcadia Wildlife Sanctuary.

The discovery of a rarity often creates the "Patagonian picnic table effect," when word spreads and many birders, bird photographers, and field ornithologists arrive on scene. Some birds take time to find, giving birders plenty of time to find other birds. A great example was October 1993 when a Harris's Sparrow was found near the Ibis Pool. It often took two hours to catch a glimpse of it, but in the meantime, Nelson's Sparrow, Lark Sparrow, Dickcissel, Dunlin, and American Golden-Plover were added. Arcadia is frequently cited on the Western Mass Birders Facebook page, which brings in more eyes and lenses after rarity sightings.

|

Blue-winged Warbler

|

Black-throated Green Warbler

|

Worm-eating Warbler

|

|

Golden-winged Warbler

|

Blackburnian Warbler

|

Ovenbird

|

|

Tennessee Warbler

|

Yellow-throated Warbler

|

Northern Waterthrush

|

|

Orange-crowned Warbler

|

Pine Warbler

|

Louisiana Waterthrush

|

|

Nashville Warbler

|

Prairie Warbler

|

Connecticut Warbler

|

|

Northern Parula

|

Palm Warbler

|

Mourning Warbler

|

|

Yellow Warbler

|

Bay-breasted Warbler

|

Common Yellowthroat

|

|

Chestnut-sided Warbler

|

Blackpoll Warbler

|

Hooded Warbler

|

|

Magnolia Warbler

|

Cerulean Warbler

|

Wilson's Warbler

|

|

Cape May Warbler

|

Black-and-white Warbler

|

Canada Warbler

|

|

Yellow-rumped Warbler

|

American Redstart

|

|

|

Black-throated Blue Warbler

|

Prothonotary Warbler

|

|

Table 3. Warblers recorded at Arcadia Wildlife Sanctuary.

Although relatively few breed there, Arcadia is a hotspot for warblers, especially in spring when trees are flowering and leafing out. To date, 34 species of wood warblers have been recorded on the sanctuary (Table 3), three of which are also in Table 2. Fall migration (i.e. late summer) can be rewarding when Orange-crowned in weedy fields and Connecticut in buttonbush stands in floodplain and hedgerows are more likely to be found.

Waterfowl and wetland-dependent birds are another highlight for Arcadia, whose sanctuary bird is the Wood Duck. Nearly every type of duck and wader has been reported, as well as several shorebirds and gulls, reflecting the mosaic of aquatic habitats.

Meadows Management

A long history of inventory, research, and habitat management on the sanctuary and a growing popularity of birding by digital photographers, as well as having me as a resident naturalist for 28 years, has contributed to an impressive list of birds. Arcadia manages approximately 150 acres of grassland, 30 acres of shrubland, 10 acres of old-field habitat, and 10 acres of weedland, and leases approximately 50 acres to agriculture. As a naturalist who also mowed the grasslands, I had my finger on the pulse of the fields and the birds, adapting management practices to suit a suite of target species.

Male Bobolink surveying his grassland domain. All photographs by the author unless otherwise indicated.

The grasslands are managed with a priority on grassland birds, a group that has been in decline. Bobolinks are the most common nesting species, with lower numbers of Savannah Sparrows and sporadic breeding by Eastern Meadowlark and Grasshopper Sparrow, the latter having nested successfully for the first time in 2019. Several opportunities take advantage of compatible uses by other groups. Unmowed grassy strips become habitat for fall and winter raptors by providing refuge for meadow vole and cottontail prey. Northern Harriers, Rough-legged Hawks, and Short-eared Owls patrol the edges of the strips. I would also mow patches of milkweed in mid-July to have their re-sprouted succulent stems available for monarch caterpillars in August and September.

The sound of the tractor is like Pavlov's bell to Red-tailed Hawks as they wait to pounce on newly exposed meadow voles. From the tractor, I have flushed the likes of Sora, Virginia Rail, and Short-eared Owl from the grasslands. Wild Turkey and American Woodcock will nest in unmowed strips that remain in spring.

I created old-field habitat for the rapidly declining Field Sparrows by putting some peripheral edges and the isolated Potash Road field on 2–3 year mowing rotations, allowing a scattering of woody vegetation. Field Sparrows are now nesting in four sites on the sanctuary, where previously they were scarce.

Shrubland is an ephemeral stage of plant succession from field to forest and is an important habitat for many declining species. Some edges and former agricultural fields in the Meadows have been managed as shrubland on a 10-year rotation (ideally). Funding, however, drives this management more strongly than biology, but Blue-winged and Chestnut-sided warblers have benefited. Long hedgerows lining Pynchon Meadow Road also provide shrubland habitat for several pairs of Willow Flycatchers, Brown Thrashers, and Yellow Warblers.

Three of twelve fledgling American Kestrels in 2020. Photograph by Kim Jones.

Having observed many fall migrants in weedy fields, I instigated a weedland management program to provide attractive habitat for a variety of seed-eating birds in fall. Tilling soil in spring encourages annual weed species that produce an abundance of seeds. In one section, tilled strips are alternated with mowed strips of perennials that contribute to cover, as well as provide a source for pollinators. Agricultural practices in leased fields may also provide an abundance of seed-producing annual weeds. This weedland habitat is particularly productive for birding, with many rarities discovered over the years and good numbers of uncommon species such as Lincoln's Sparrow. Weedy fields may seem unkempt to some, but to birders, they are Eden. I recall a former president of Mass Audubon showing the Meadows to a group of donors and apologizing that the fields don't usually look that messy, but then transforming with enthusiasm when they started seeing birds everywhere!

Wood Duck, the sanctuary bird of Arcadia.

Numerous bluebird and strategically placed kestrel nest boxes are scattered around the fields. Eastern Bluebirds typically occupy 6–8 boxes, with dozens of Tree Swallows in the rest. American Kestrels have successfully fledged 41 young from 10 nests since 2015, with three pairs raising four young each in 2020. Several duck boxes in the floodplain are used occasionally by Wood Ducks for nesting and also by Eastern Screech-Owls for roosting. My son and I have often found beaks and feathers of Northern Cardinals and Blue Jays in the boxes.

Getting There

Arcadia Wildlife Sanctuary is nestled between the quaint cities of Northampton and Easthampton, Massachusetts. Coming from far afield, take Interstate I-91 to Exit 18-Route 5-Northampton Center. Head south on Route 5 for 1.4 miles and turn right on East Street in Easthampton. Continue for 1.2 miles and turn right on Fort Hill Road with a Mass Audubon sanctuary sign at the intersection. (See map.) Scan Danks Pond for ducks and herons on your right on the way in from Fort Hill Road. In 0.5 mile, bear right onto Old Springfield Road and take a quick left onto Combs Road to the Visitor Center parking lot. Local folks can come in via Route 10 north from Easthampton or south from Northampton to Lovefield Street where you will follow the signs to Clapp Street, bearing left onto Old Springfield Road and taking a quick left onto Combs Road.

To reach Arcadia Meadows and the Oxbow, continue straight on Old Springfield Road past the Combs Road entrance. A metal bridge spans the mouth of the Mill River, giving views of the Oxbow. The one-lane bridge can be submerged under floodwaters in spring and traditionally closes in winter, though plans for a new bridge have been in the works. After the bridge, the floodplain forest gives way to the open grassland and agricultural meadows. Fields are located down Old Springfield Road and Pynchon Meadow Road. The Ibis Pool is on the south side of Pynchon Meadow Road. The area known as Ned's Ditch is part of the 800-year-old oxbow that bisects the meadows and is opposite the Oxbow Water Ski Show Team boat ramp.

Birding Arcadia

Wild Turkey at Visitor Center kiosk.

Visitor Center: Mulberries to Tulip Tree Trail

From the Visitor Center parking lot, some birders and photographers need not go any farther. In June and early July, the mulberry trees and shadbush are teeming with birds. The ripening time coincides with fledgling periods for most songbirds. Family groups with parents feeding offspring are common sights. Baltimore and Orchard orioles, Scarlet Tanagers, Rose-breasted Grosbeaks, Cedar Waxwings, Blue Jays, American Robins, Gray Catbirds, and House Finches flash their brilliant colors among the hordes of dull juvenile European Starlings. But many other species join in that are less often thought of as fruit eaters, including Red-bellied, Pileated, Hairy, and Downy woodpeckers, Northern Flicker, Yellow-bellied Sapsucker, Eastern Kingbird, Red-eyed Vireo, Wood Thrush, Eastern Towhee, Brown Thrasher, Mourning Dove, and Wild Turkey.

A kiosk at the trailhead displays a map of the sanctuary, and trail maps are available at the Visitor Center. Cut across the field with the sensory trail to the boardwalk by Fire Pond and the vernal pool, a good place for Black-and-white Warbler and Northern Waterthrush in spring. Barred Owl has often put on a daytime show. In April a cacophony of wood frogs that deposit masses of jelly-encased eggs can be heard here, and several other frogs and turtles can also be viewed or heard. Continue behind the Visitor Center and head down the Tulip Tree Trail, noting the majestic twisted-trunk tulip tree on the right. On the left is a wet area and scattered crabapples that usually attract a variety of birds in spring.

The Orchard

At the junction with the Cedar Trail and Horseshoe Trail, continue on the Horseshoe Trail to bird the hedgerow, either from the trail itself or on the side of the farm field. The hedge is birdy and produced the likes of Yellow-throated Warbler and Western Tanager in November 2017. Some folks get to the hedge from the parking lot by going back down the entrance road and entering near the solar panel array. A grassy trail is maintained that leads past the hedgerow to the Old Orchard, a former apple orchard with a figure-eight trail amid a thicket of shrubs and scattered trees. The Old Orchard Trail connects back to the Horseshoe Trail, which loops around to reconnect with the Cedar Trail.

Inside the Horseshoe Trail-Cedar Trail loop is an orchard, where a variety of crabapples and other fruiting trees have been planted, including three large, prolific Korean mountain ash, one castor aralia, scattered black cherries, and a tangle of wild grapes and invasive fruit-bearing shrubs. This area is a major destination in spring when the trees are in bloom, and again in fall when the berries are ripe. The flowering crabapples in May attract numerous warblers, including Nashville, Wilson's, and Northern Parula, along with Orchard and Baltimore orioles, Ruby-crowned Kinglets, and Indigo Buntings. American Redstart, Chestnut-sided Warbler, and Rose-breasted Grosbeak breed there. Black-billed Cuckoo can also be found in some years. When the fruit is ready, or sometimes sooner, flocks of Cedar Waxwings and American Robins descend on the scene like vultures on carrion. In some winters, you may find Pine Grosbeak, and if you are really lucky, a Bohemian Waxwing.

At the end of the Horseshoe Trail, the Old Orchard area is great in spring for migrant warblers. The mix of open woods, thick shrubs, and tall trees brings in a variety of birds, with chances for good looks. Search the thickets for Nashville, Wilson's, Magnolia, Black-throated Blue, Canada, and Mourning warblers. Hooded and Worm-eating warblers joined the mix in 2019. At mid-level, you'll find American Redstart, Yellow-rumped, Blue-winged, and Prairie warblers, with Tennessee Warblers gleaning the American elms. When the oaks and hickories are in bloom or just leafing out, you'll get warbler neck by scanning the tops for Cape May and Bay-breasted warblers. Spruce Corner is a good place to find Blackpoll Warbler.

Mill River Floodplain and Arcadia Marsh

The Fern Trail spurs off of the Horseshoe Trail and leads through exemplary floodplain forest of silver maple, green ash, pin oak, black birch, and shagbark hickory, with glimpses of the Mill River and Arcadia Marsh. Scan the marsh from the trailhead, and then continue down to the observation tower. The spiral staircase has some sway to it, but that is part of the design. Notice the high-water markers on the pole as you ascend. Some mighty big floods occurred in the 1930s. The tower provides a good look at the marsh, which has two channels around a vegetated peninsula with abundant spatterdock, wild rice, and Walter's millet. The Fern Trail is a good place for spring ephemeral wildflowers.

Clay-colored Sparrow.

Ice-out kickstarts the spring waterfowl migration season, sometimes as early as February. Among the large flocks of Canada Geese, look for Cackling, Snow, and Greater White-fronted, or even Ross's. Rafts of Mallards and American Black Ducks stage in the marsh during the day, but most leave in the evenings to roost elsewhere—Nashawanuck and Lower Mill ponds in Easthampton—when the flocks of geese come in to roost in the marsh. Less common dabblers include Green-winged Teal, American Wigeon, and Northern Pintail. Scan for Gadwall and Northern Shoveler. Divers are more common in the Oxbow, but Common and Hooded mergansers and Ring-necked Ducks often make their way into the marsh when the water is high. Nearly anything is possible. In 2020, a Greater White-fronted Goose mingled with Canada Geese and buttonbush in Arcadia Marsh for a spell in early March.

When the water level is high, waterfowl congregate to feed or roost. Look for grebes and coots as well. During low water, exposed mudflats often attract shorebirds and waders, including both yellowlegs and Least and Pectoral sandpipers. Keep an eye out for an occasional dowitcher or plover, Glossy Ibis, or Black-crowned Night-Heron, along with other herons and egrets. The marsh is a good place to view broods of waterfowl chicks, including Wood Duck, Mallard, and Common Merganser. In summer, watch for Cedar Waxwings and swallows picking off newly emerged damselflies on their fateful maiden voyages. In September and October, the wild rice and millet provide a feast for hordes of blackbirds, which in turn attract Northern Harriers and Cooper's Hawks. Eagles and Ospreys and Belted Kingfishers also hunt for fish in the marsh, which is a nursery for northern pike. If any of the blackbirds have white wing patches, they may be Yellow-headed Blackbirds.

Near the end of the Fern Trail, try to find another majestic tulip tree—over 120 feet high—towering over its neighbors. The Fern Trail connects to the River Trail, which continues along the Mill River and provides closer views of the river. You might catch sightings of beaver, muskrat, river otter, or mink. Listen for Pileated Woodpecker, Yellow-bellied Sapsucker, Yellow-throated and Red-eyed vireos, Scarlet Tanager, Great Crested Flycatcher, Louisiana Waterthrush, and Brown Creeper. The trail leads to Wood Duck Pond, where you will find a smaller version of Arcadia Marsh at closer range. A mudflat at the riverbend can have shorebirds when exposed.

Juvenile Northern Harrier patrolling the grasslands with tall, unmowed strip of switchgrass showing in the background.

Mixed Lowland Forest

At the intersection of River Trail and Old Coach Road Trail, you have several options, depending on how much time you have and how long a walk you want to take. (See map.) The other trails loop through mixed oak-maple-white-pine-hemlock forest with mountain laurel, witch hazel, and winterberry understory where you will find Eastern Wood-Pewee, Wood Thrush, Ovenbird, and Scarlet Tanager. Stands of white pine are sure to have a pair of Pine Warblers. Acadian Flycatcher was singing in Tupelo Swamp off Sassafras Trail in 2019 and is a bird to watch for in the years ahead. To continue on this route, stay on the Old Coach Road Trail until you find your way to the Woodcock Trail, where you will not likely find American Woodcock but will get views of a perched swamp down the slope. Deer-watching is good there, and a black bear may wander through the swamp for an early spring salad of skunk cabbage. Birds may be at eye level on the ridge. The Woodcock Trail leads back to the boardwalk and sensory trail and Visitor Center.

Arcadia Meadows

To get to Arcadia Meadows, walk or drive from the parking lot back to Old Springfield Road and turn left. Soon you will descend to the mouth of the Mill River, where you will risk life and limb crossing a 40-year-old, one-lane, 10-year temporary bridge. Not yours, but the life and limb may belong to anglers on the narrow bridge. The bridge is closed in winter and often floods impassably in spring. Beyond the bridge, the floodplain forest opens up to grassland and agricultural fields called Arcadia Meadows, formerly known as the West Meadows. The Meadows can also be accessed via Fort or Olive streets that lead to Old Springfield Road, or Park Hill Terrace that leads to Pynchon Meadow Road. All three access roads are subject to spring flooding. Pynchon Meadow Road and part of Old Springfield Road are dirt roads that often have hazardous potholes, washboards, moguls, and deep abysses, especially Pynchon Meadow Road.

Once in the Meadows, start scanning the fields from the roadside for Northern Harrier, American Kestrel, and Bobolink, and keep an eye on the sky for Bald Eagle and Red-tailed Hawk. At the right times, most raptors can be seen in the Meadows. The utility lines on Pynchon Meadow Road usually have perching birds, and the hedgerow beneath is a hub of activity. When the road is in bad shape, puddles form and become birdbaths. Wait at a good distance from a puddle long enough and several hard-to-see birds, such as White-crowned Sparrow, may come out into the open for a good view. Merlins know this and will cruise right down the road, sometimes within inches of observers, to catch unsuspecting prey. An observation blind sits on the raised bed of the old trolley line that crosses the western meadows. Look for Yellow-breasted Chat and Connecticut Warbler in the thickets.

A major highlight and rare bird magnet is the Ibis Pool on the south side of Pynchon Meadow Road. The area is a deep swale that retains floodwater in spring and sometimes autumn. It is bordered by weedy fields. It got its name when a Glossy Ibis showed up in the 1970s. The open pool was historically adjacent to agricultural fields, most recently potatoes in the early 1990s. Farmers would plow as close to the pool as possible. It provided open water for waterfowl and waders, mudflats for shorebirds, and weedy areas for sparrows. When the agricultural fields were acquired in 1993, the land adjacent to the Ibis Pool lay fallow, with acres of annual weeds providing food and cover for droves of seedeaters. Over the years, a wetland marsh community with cattail and smartweed has developed in the pool area, and perennial goldenrods and others have taken hold in the adjacent field; spring tilling encourages weedy annuals. Marsh and Sedge wrens, Blue Grosbeak, Lincoln's, Swamp, and Savannah sparrows, Common Redpoll, and Pine Siskin, as well as many vagrants, keep birders on their toes.

Other areas around the Meadows are grassland, shrubland, and agricultural crops that mesh with bird habitat. While Bobolinks prefer the interior of grasslands, Savannah Sparrows and Grasshopper Sparrows are associated with the grassland-cropland edge or areas with sparse grass. The crops are usually squash alternating with corn along Pynchon Meadow Road, or a variety of vegetables bordered by uncultivated weeds off Old Springfield Road. A cucumber farmer would often wait until July to plant the fast-growing crop, allowing Savannah Sparrows the opportunity to breed in the fallow field before cultivation. Outside the growing season and when freshly plowed, the fields harbor large flocks of Horned Larks, Snow Buntings, and American Pipits, and sometimes shorebirds. Search among them for Lapland Longspur or even a Northern Wheatear. Winter raptors, such as Northern Harrier, Rough-legged Hawk, and Short-eared Owl hunt both the grasslands and agricultural fields.

Ned's Ditch and the Old Oxbow

Arcadia Marsh is at the southwest prong of the old oxbow arch, while Ned's Ditch is at the southeast end. Nobody knows who Ned was, but the swamp forest and buttonbush marshes are a botanical gem. The birdlife is also bountiful. The Ditch has low, wet, marshy swales; higher, dryer, forested berms; and open ponds connected during high water through dense buttonbush marsh that provides cover for Wood Ducks and Soras. A Northern Shoveler and Blue-winged Teal lingered with Mallards and American Black Ducks in Ned's Ditch in March and April 2020.

Ned's Ditch has been the scene of much avian drama over the years. In 1995 a pair of Great Blue Herons began nesting and started a rookery that built up to a high of 59 nests in 2009. Most of the nest trees were alive until a prolonged flood in 2009 killed over half of the trees. Supporting limbs gradually began to shed in the following years. In 2012 a pair of Bald Eagles usurped a heron nest, causing much unrest in the heronry. The eagles preyed on young herons. Two years later a pair of Great Horned Owls moved into another heron nest. Heron numbers plummeted to zero by 2018, though two pairs successfully nested farther away in 2019.

Common Redpoll on evening primrose.

The eagles had troubles of their own, having raised only two young in five years, when tragedy befell the pair in 2017. The female was struck and killed by a car on Route 5 near the Oxbow. Her bands revealed she was 28 years old and born in one of the first two nests at Quabbin Reservoir during the eagle restoration program (French 2017). The male appeared to have a new mate already a few days later. They did not attempt to nest that year but successfully raised three young in both 2018 and 2019. A field-readable photo of the male's leg band by Kim Jones revealed he was born in Massachusetts in 2010, so it may have been a completely new pair after 2017. In 2020 a male interloper tried to take over the territory shortly after the pair began egg-laying. The resident male vanished for a few days but made a return to help his mate ward off the intruder, lay a new egg, and successfully raise one young.

The 2009 tree-killing flood was a boon to woodpeckers, and other birds have thrived in Ned's Ditch, either during the flood season or in dry years when the bottoms of the ponds are exposed. Northern Flicker and Red-bellied Woodpecker are common. Green Heron and Sora are regular breeders. Blue-gray Gnatcatcher is a relatively recent addition to the breeding avifauna. Flocks of more than 30 Great Egrets have taken advantage of the dry ponds, and Glossy Ibis, Tricolored Heron, and Little Blue Heron have made cameos. The floodplain surrounding the old Mill River channel that enters Ned's Ditch hosted an immature Red-headed Woodpecker in the same location two years in a row.

The Oxbow

Arcadia abuts the 1840 Oxbow on the eastern side of the Meadows, offering looks into the open-water system. Cut off from the main stem, the slow current provides refuge for waterfowl, especially when the Connecticut River is raging. Shortly after ice-out, flocks of mergansers, Ring-necked Ducks, and cormorants build into the 100s before moving north as Vermont and New Hampshire thaw out. Less commonly, you might encounter Bufflehead, Ruddy Duck, Canvasback, Redhead, or Long-tailed Duck. Either scaup species might hang out with the flocks of Ring-necked Ducks. Several other divers are possible, including Horned, Red-necked, and Pied-billed grebes. Common and Red-throated loons have been recorded. Rare gulls, particularly Iceland, Glaucous, and Lesser Black-backed, but also Black-headed and Laughing gulls may mix with the common species. Caspian and Common terns sometimes touch down for a day or two on their way to or from their inland breeding grounds. And on two occasions, an American White Pelican filled its beak and belly with Oxbow fish. When the flooding has subsided, or during low-water periods, check the sandbar at the Oxbow Marina harbor for shorebirds, terns, gulls, and herons.

The Oxbow is also a great place for eagle watching, particularly in winter and early spring with some ice and open water. Several immature birds will congregate and mingle with the resident pair. Aerial acrobatics of courtship, combat, or practice are on full display. Peregrine Falcon and Osprey also pursue prey there at times, and the Hadley Gyrfalcon of 2013 undoubtedly checked out the Oxbow, but nobody reported it.

References

David McLain is a wildlife biologist with degrees in the field from the University of Maine and University of Massachusetts. He has expert level experience with birds, freshwater mollusks, odonates, butterflies, orthopterans, fish, herps, and plants. He has worked in Puerto Rico on the Puerto Rican Parrot Recovery Project, Scotland and Iceland studying genetics of Atlantic Puffins, Panama on genetic differences between birds on the Pearl Islands versus the mainland, the Bahamas with hummingbirds, and numerous bird population studies in Maine, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts. Dave lived and worked at Arcadia Wildlife Sanctuary for 28 years, studying everything, before headquarters staff changed direction.