Mark Lynch

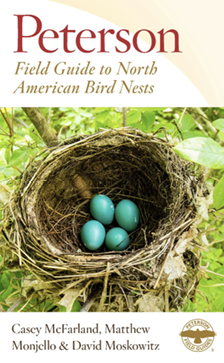

Peterson Field Guide to North American Bird Nests. Casey McFarland, Matthew Monjello, and David Moskowitz. 2021. Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

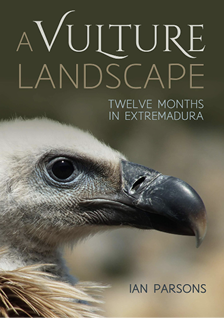

A Vulture Landscape: Twelve Months in Extremadura. Ian Parsons. 2020. Dunbeath, Caithness, Scotland, United Kingdom: Whittles Publishing Ltd.

Although these two books are about birds, they could not be more different. One book is a revised, updated, and expanded field guide to North American bird nests written by three authors. The other book is one man’s paean to just one group of birds and the unique region where he has watched it for years.

When you find a nest, be open to a range of possibilities, and look for interesting clues. (p. 7 Peterson Field Guide to North American Bird Nests)

When you find a nest, be open to a range of possibilities, and look for interesting clues. (p. 7 Peterson Field Guide to North American Bird Nests)

In the introduction to the new Peterson Field Guide to North American Bird Nests, the three authors cite the 1975 Peterson Field Guide to Birds’ Nests by Hal H. Harrison. That old field guide had been a favorite of theirs, but now their personal copies are dog eared and worn, and it has gone out of print. They were a good choice to write and edit this updated and expanded version of that important guide. This new guide covers 650 species and has 750 color photographs and several line drawings. Under species accounts there is typically one accompanying color photograph, but for some species there are more. Under Great Blue Heron there is a shot of a rookery as well as a close-up of a single nest (p. 189). Marbled Murrelet rates four nest shots. This seems odd since so few of us will ever just stumble across the unique nest of that Pacific alcid. I will explain why below.

The introductory sections, pages 6–65 of this guide, are well worth reading by all birders. The authors begin with a cautionary note to discourage birders from getting close to birds’ nests. “Well-intentioned curiosity about a nest can too easily lead to the demise of its contents.” (p. 2)

It is always tempting to get close to any bird nest just to see what is going on or to take a photograph, but readers of this guide are well warned by the authors to give nests some distance.

Learning to identify nests starts first with acknowledgement that, for birds, nesting is a difficult and taxing behavior that often ends in failure. Our interest in this aspect of avian life can have real consequences for the birds we so admire—many eggs and nestlings never make it through the hurdles of this initial stage of life, even without human disturbance contributing to the odds. (p. 2)

Of course, identifying a nest while the species is in the process of building it is no problem. But identifying nests after the birds have fledged, with no adults around, presents a challenge. The birder has to be a bit of a detective. First, you must take into account how old the nest is. By the end of a breeding season, nests can be quite a mess, looking worn, dirty, misshapen, and some of the finer materials may be gone. Take stock of what you see, the materials that are left, what you can make of the structure, and finally, consider the location.

Included in the Peterson Field Guide to North American Bird Nests is a five-page “Nest Key” (p. 11–15), which is a great place to start. Examples of these basic “nest categories” (p. 11) include “Outer layer decorated with lichen flakes” (p. 12), a design used by hummingbirds, peewees, and gnatcatchers. Each category directs the reader to several groups of birds to consider as the builder of the nest. One category includes only one species. Under the category “No nest, in divot in moss on branch of mature conifer in old-growth forest” (p. 15), only one species is listed: Marbled Murrelet. This unique alcid’s nest is “usually 1082 m high in a mature tree, typically in the top half to third of the canopy.” (p. 150) Their nest is not even found in trees right along the coast but found in trees 12.4 km or more from the coast. Which is why, as I mentioned above, you are very unlikely to just stumble across this nest. Unless you are a lumberjack.

We assume that all birds instinctively know how to build their nests well, but this is not always the case.

It is important to note that not all nests are built well. At times, birds may build suboptimal, poorly insulated nests, perhaps resulting in the stunted development of young or an energetically costly increase in brooding time. (p. 41)

This reminded me of a time when, conducting the Breeding Bird Atlas II, we watched a nest-building Eastern Peewee deep inside eastern Quabbin. The bird had constructed the outer perimeter of the nest and part of the base, but most of the bottom of the nest was open. The bird kept putting materials in the base, but the potential nest bits just fell through the hole. We watched this bird for thirty minutes as it continued to try to line the bottom of the nest, and the materials kept falling through. It was like watching an avian Sisyphus.

Some nesting species closely associate with other nesting species to enhance the chances of their offspring’s survival.

Other species will seek the “protection” of other animals, birds or otherwise, benefiting from some additional neighborhood muscle. Using the defensive aggression of another species increases the odds of reproductive success, and such associations can reduce nest predation as well as brood parasitism. Bullock’s Orioles, for example, may build their nests near those of the predator-mobbing Yellow-billed Magpie. Many species may occupy nest sites near wasp or ant nests, limiting the approach of terrestrial reptiles and small mammals, and species comfortable among human habitation (e.g. Barn Swallows) effectively minimize the risks posed by wild predators. Similarly, some passerines such as House Sparrows will nest within the large nests of predatory birds such as eagle. (p. 21)

If you have ever watched broods of Wood Ducks, Hooded and Common mergansers, you will be interested in this guide’s sections on “Brood Parasitism” (p. 33) and “creches.” (p. 25) Many readers will be familiar with Brown-headed Cowbirds as brood parasites. You may not realize that it is also a behavior among certain species of waterfowl that breed in Massachusetts. Brood parasitism can be intraspecific, parasitizing the same species, or interspecific, parasitizing different species. Cowbirds are interspecific brood parasites. Wood Ducks are common “egg dumpers,” with some females laying their eggs in the cavity of another Wood Duck or sometimes in the nest of a Hooded Merganser.

At north Quabbin and in the Berkshires, I have seen female Common Mergansers with very large numbers of ducklings swimming frantically behind them. Is this an example of intraspecific brood parasitism or something else? I was told long ago that Common Mergansers often form a crèche with one or more females watching the young of two or more nests. Here is what the Peterson Guide to North American Bird Nests says about crèche formation:

The young of many species that nest colonially, such as Royal Tern, Pinyon Jay, and Common Eider, congregate together in crèches. Among other benefits, crèches reduce the risk of predation of any one individual and allow for fewer adults to stand guard while others spend time foraging. Young may be identified among the group and fed by their parents, or, depending on the species, fed also by other adults. (p. 29)

Common Mergansers are cavity nesters and do not nest colonially. Doing some further reading in the Birds of the World website, I learned that the jury is still out on whether Common Mergansers form crèches or if all the records of abnormally high broods of ducklings watched over by one female are just intraspecific brood parasitism. Either way, it is always an interesting behavior to watch.

This is a guide not just to the physical structure of nests, but also a guide to the nest building behavior of those species, as well as how they rear their young. In the introductory section there are essays worth reading on the evolution of bird nests, nests and bird biology, the energetic costs of nest construction, and avian mating systems and behaviors.

This guide covers all of North America north of Mexico. The habitats here range from “tropical deciduous forest to Arctic tundra” (p. 3), so the variety of nest materials and nesting sites described in this book is mind-blowing. The authors describe the species accounts as streamlined, but they still contain a wealth of detail. Most accounts include notes on “Habitat” (generally where the bird lives), “Location and Structure” (where specifically within that habitat the nest is built, and what materials are used to construct the nest, and what it looks like), “Eggs” (the typical clutch size and size of the eggs), and finally “Behavior” (are they colonial nesters or are they solitary nesters, for example). A small but detailed range map is included for every species.

There are also extensive general introductions to the nesting behavior of groups of birds like gulls (p. 157) and hummingbirds (p. 107). An interesting inclusion is a gallery of goose and duck feathers (p. 63–66) to aid in the identification of a down-lined nest. Frankly, most of these photographs at first glance looked like “white and fluffy” feathers to me, so I am not sure how useful this section will be. More useful are the plates showing all the various egg shapes as well as the categories of egg markings.

Even the organization of the species accounts in this guide aids in the identification of a nest. For instance, the section of ducks is divided into sections on “cavity nesters,” “overwater nesters,” and “ground-nesting” ducks. The photographs included in the species accounts are by necessity small, but generally of good quality. It was interesting to see a photograph of a Purple Martin nesting in a natural cavity rather than a martin house or gourd.

Authors McFarland, Monjello, and Moskowitz have done a masterful job updating and expanding what was a decades old popular field guide. The Peterson Guide to North American Bird Nests is one of those basic texts that should be in every birder’s library.

To watch vultures over the plains, to gaze at a huge bird as it effortlessly glides through the air above the oaks of the dehesa, is an exhilarating experience that we should all have. (p. 1, A Vulture Landscape)

To watch vultures over the plains, to gaze at a huge bird as it effortlessly glides through the air above the oaks of the dehesa, is an exhilarating experience that we should all have. (p. 1, A Vulture Landscape)

Ask anyone what their favorite birds are and you will get answers like owls, hawks, hummingbirds, bluebirds, and parrots. Serious birders might give more unexpected answers like shorebirds or American warblers. Personally, I love rails, particularly Virginia Rails, for reasons too long to write about here. But few, if any, people you know would likely list vultures as their favorite birds. After all, vultures are not particularly colorful, they eat carrion, and they have been symbols of death since ancient times. What’s to like? Well, Ian Parsons would beg to differ with that opinion. Give him a chance, and he will positively wax poetic about vultures:

Vultures are brilliant birds; birds that first captured my imagination as a child watching wildlife documentaries as these huge birds swarmed over large mammal carcasses on the African savannah. I can still remember seeing my first real-life one, even though it was a quarter of a century ago—an indelible memory of a Griffon Vulture drifting high in the blue sky of a Spanish spring. I was instantly hooked. (p. 1)

Not only does Parsons thoroughly enjoy watching vultures, he loves watching them in one particular spot, the Extremadura area of central western Spain. A Vulture Landscape is his attempt to convey his excitement watching these magnificent birds in this dramatic, arid, barren steppe country. The Extremadura has long been recognized as an area important for wildlife. There is a major reserve and national park at Monfragüe. There is also a Tagus River National Park. Though two major rivers cross the area, the Tagus and Guadiana, much of the Extremadura is open arid country with scattered rocky hills. Here are also found dehesas. These are large areas of cultural landscape used primarily for grazing by Spanish fighting bulls and Iberian pigs, among other livestock. This ensures a constant source of carcasses for vultures to feast on. These open spaces are dotted with small trees, mostly species of oaks like Holm and Cork. Though dehesas are agricultural spaces, they are also enjoyed by many species of raptors and other birds.

The book is divided into twelve chapters, one for each month of the year. Parsons knows this area well because he has lived here for years, though not currently, and he regularly conducts trips to the Extremedura for birders. The breeding vultures in Extremadura are the Griffon Vulture, the Egyptian Vulture, and the Eurasian Black Vulture of Europe and Africa. This latter species (Aegypius monachus) is not related to the North American Black Vulture (Coragyps atratus) and is visually like a more formidable and darker Griffon Vulture. The Griffon and Black vultures will remind North American readers of what they see deified in Egyptian art or even the vultures as they are shown in old cartoons with the ruffled collars and large beaks. These are big, powerful-looking birds. The Egyptian Vulture is the odd bird among the group, being smaller and mostly white. In the Pyrenees of Spain you can also find a small population of the Bearded Vulture, also known as the Lammergeier.

As I learned in A Vulture Landscape, there is another species of vulture that in recent years has been regularly, if rarely, showing up in the Extremedura. This is the Ruppell’s Vulture. The nearest population of this species to Extremadura is Senegal in west Africa. Most sightings of this rarity (in Europe) have been in June. Could the Ruppell’s eventually breed in the Extremadura? Only time will tell. The White-rumped Swift, another African species, has recently colonized Spain.

The whole area is rich in bird life. Bonelli’s, Golden, and Spanish Imperial eagles share the plains and hills of Extremedura with the vultures. Larks found here include Crested, Short-toed, and Calandra. There are Little and Great bustards. Other species that are found breeding in the Extremadura include Rock Bunting, Blue Rock Thrush, Black Redstarts, and Great Spotted Cuckoos. All of these birds make an appearance in A Vulture Landscape.

Spring migration begins in earnest in February with the arrival of the Great Spotted Cuckoos, and fall migration is a time of passing flocks of Common Cranes. In winter it does get cold, and there is ice on small ponds. Most of the Egyptian and Griffon vultures migrate out of the area, but the Black Vultures remain. In summer, the Extremadura can get very hot. August in particular sounds like a tough time to visit.

Desiccated and devoid of moisture, the land is exhausted by the aridity of the long punishing summer. Mini, self-generated, whirling dervish dust tornadoes spontaneously spin into life before burning themselves out across the open, exposed plain. Great Bustards blur and break up in the wavy sea of heat haze that has drowned the parched land. (p. 43)

Throughout the book, Parsons touches upon many other topics concerning vultures. Particularly concerning is the massive die-off of vultures in India due to the ingestion at dumps and sewer areas of the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) called Diclofenac. You would think a group of birds that survive on carrion could resist anything humans could throw at them, but this is a serious and ongoing avian catastrophe.

Not only is the Extremadura a great place to watch these magnificent vultures soar and devour carcasses en masse, it is also a fine place to see them nesting. But unlike watching flying birds soar over the dehesas, you have to travel to more remote areas of the Extremadura to find Griffon Vulture nests.

The real excitement in watching vultures’ nests comes in the places you have to be to do so. They are wild places, places where our species is not comfortable or numerous. Places like this—a rocky arc of hills on the western edge of the region with Portugal visible on the horizon. (p. 13–14)

I have only birded the Catalonia region of Spain, but we stumbled across the nests of Egyptian and Griffon vultures. Seeing the hulking Griffons tending a nest high in a rocky outcropping is indeed a dramatic sight.

A Vulture Landscape is a unique book. You will learn a lot about the behavior of the breeding vultures of the area, as well as the other birds to watch. This is also a wonderful portrait of the land and people of the area. It is illustrated with many fine color photographs. Finally, A Vulture Landscape is about the love one man has for a group of birds and the special place they are found.

In some places, vultures are common, a feature of azure blue skies and the harsh landscape below them. Extremadura in central Spain is one of these places. It is a vulture landscape. (p. 5)

References

- Harrison, Hal H. 1975. Peterson Field Guide to Birds’ Nests. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Pearce, J., M. L. Mallory, and K. Metz. 2020. Common Merganser (Mergus merganser), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.commer.01

To listen to Mark Lynch’s interview with Ian Parsons for WICN, go to: <https://www.wicn.org/podcast/ian-parsons/>

To listen to Mark Lynch’s interview with Casey McFarland, one of the authors of the Peterson Field Guide to Bird Nests of North America, go to: <https://www.wicn.org/podcast/casey-mcfarland/>