Mark Lynch

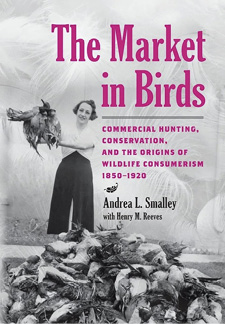

The Market in Birds: Commercial Hunting, Conservation, and the Origins of Wildlife Consumerism 1850-1920. Andrea L. Smalley with Henry M. Reeves. 2022. John Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, Maryland.

The Market in Birds: Commercial Hunting, Conservation, and the Origins of Wildlife Consumerism 1850-1920. Andrea L. Smalley with Henry M. Reeves. 2022. John Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, Maryland.

“If I had the last pair of gamebirds on earth, I’d ring their necks.”

(E.S. Bond, game dealer, quoted on p. 31)

There was a period in America’s past when wildfowl became a commodity like oil or timber. This period of the commodification of ducks, geese, grouse, and shorebirds had a disastrous effect on bird populations. Beginning shortly after the Civil War and continuing through the Gilded Age into the early twentieth century was the time of the market gunners whose sole goal was to kill as many birds as they could and to sell them to markets and restaurants across America and even overseas. The Market in Birds by Andrea L. Smalley is a scholarly history of this horrifying yet fascinating time that eventually encouraged state and national legislation to be enacted to protect wild birds, although for some, like the Passenger Pigeon, these important laws would come too late.

The modern market in birds was short-lived but broadly influential. At its height between 1870 and 1900, market hunting was a huge and lucrative business across much of North America, its rise and fall occurring simultaneously with the emerging Progressive Era conservation movement. This was no coincidence. Market hunting in its modern form became arguably the single most important issue for the initial generation of self-proclaimed wildlife protectors. (p. 4)

Andrea M. Smalley is professor emeritus at Northern Illinois University. The listed co-author, Henry M. Reeves, died in 2013. Henry M. Reeves, known to friends as “Milt,” was the chief of migratory bird management for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Author of several books and papers on migratory birds, Reeves had been researching for years the connections among migratory birds, hunters, the market, and consumers, but died before he could finish his planned book on that subject. Smalley was contacted by the Reeves family, and Milt’s wife, Merilyn, organized his unfinished chapters and handed over to Smalley these chapters as well as boxes and file cabinets of material Henry Reeves had gathered for his book. Smalley used these considerable resources as the core material for The Market in Birds.

One of the key documents about the market gunning period was the memoir The Shadow of a Gun by Henry Clay Merritt. He was an early market gunner himself who later retired from the business and wrote this book. In it he prophesized a rapid decline and disappearance of many of the species he himself made a living killing.

Merritt pitied the “despairing huntsman” of this modern age, who would find that “the plough of the farmer has made the prairie, once vocal with wild birds, only a desolate solitude.” Future generations would never see the avian abundance of the past, which had been “a sight grander than any temple and more ravishing to the hunter than the streams of Paradise. (p. 1)

Purple prose from a man who basically killed everything he saw to turn a profit. Merritt writes about taking a walk one day and seeing numerous game birds.

The first clue to his future appeared as he was walking into town one day. Noticing the fence rows lined with prairie chickens, he “began to study what [he] could do with them.” Golden Plovers dotted the skies, but he could see “no way of turning them into cash.” (p. 17)

Thus began the era of market gunning. Several technological inventions happened at this time that enabled thousands of men with guns to travel to places where the wildfowl were, kill thousands of them in a short time, and then ship the dressed bodies to places far and wide. Prior to this time amateur hunters, of course, shot birds for local consumption. But those corpses never traveled far, being used often for the home table or maybe they would sell them locally. But the coming of the railroad and the automobile allowed hunters to go where the greatest concentrations of birds were, and these hunters could shoot many more wildfowl for the commercial market than they would use personally. Keep in mind, there was no such thing as “bag limits” at this time.

Railroads opened new fields to commercial hunters, offering them faster and quicker transport to wildfowl habitats farther away. When the Des Moines River flooded in the late nineteenth century, attracting an unusually vast concentration of ducks, the Rock Island Railroad brought hundreds of gunners to the area within a matter of days, leading to what become known as “The Big Slaughter.” In the twentieth century, automobiles brought even greater mobility to both commercial and recreational hunters, raising concerns among some that there would be no place left where wildfowl could remain unmolested. (p. 35)

There were even dedicated “hunting cars” (p. 138) of certain railroads that carried large numbers of hunters to where the birds were and then brought them back so they could sell their birds to the market.

Thanks to new advances in refrigeration, dead birds could be preserved and then shipped to the most lucrative markets without spoiling. The convergence of these technological developments helped begin the commodification of wild birds. These market gunners were part outdoorsmen but also part businessmen.

The great refrigerator of the A.&E. Robbins Company in New York City could hold up to fifty tons of game from which supply it could make large shipments to markets as far away as Europe. Between 1869 and 1909, the number of commercial refrigeration facilities in the United States rose from four to more than two thousand. (p. 59)

In the early days of market gunning, carcasses of wildfowl were shipped in barrels with maybe some sawdust and ice, but no real refrigeration. Of course, the meat spoiled, but at that time some people actually liked their game that way.

Preservation of wildfowl meat was initially of less concern, reflecting the widespread belief that game birds should be aged to improve taste. Well into the nineteenth century, many connoisseurs argued that game birds needed to be hung for several days before consumption. Others disagreed. Chamber’s Encyclopedia noted in 1889 that game was “generally eaten in this [putrefied] condition,” and though it was “readily digested and admirable in flavor,” such “high” meat was also “apt to disagree with many people.” In worst cases, its ingestion could result in “fatal consequences.” (p. 56)

Market gunning rapidly became big business, with many jobs involved. There were the hunters, of course, but then there were the “game dealers,” the men who organized where the birds would go. There were people to run the refrigeration plants and people to drive away the cartloads of birds to their distribution points. There were also the salaried employees of larger commercial concerns such as markets, hotels, and restaurants whose job it was to procure the game that was featured on their menus. Market gunning became an occupation in which people could hope to make a good deal of money. How many market gunners were there? It’s tough to know exactly, but Smalley gives some interesting insights.

Given this diversity, it is almost impossible to know how many market hunters were active at any one time in the locality, region, or nation. Scattered anecdotal accounts offer only clues. One commentator suggested in 1872 that more than a thousand men in Louisiana earned “a fair living during four months of the year, shooting [waterfowl] for the New Orleans market.” Henry B. Roney, a crusader for passenger pigeon protection, claimed that about five thousand men in the United States worked annually as pigeoneers, while biologist T. Gilbert Pearson reported that between 1903 and 1910 some four hundred duck hunters were working in Currituck County, North Carolina, who marketed no less than $100,000 worth of game annually. (p. 23)

Massive passenger pigeon hunts could involve thousands of participants, from netters and trappers to the itinerant “buyers, shippers, packers, Indians, and boys” who were all “engaged in the traffic” at a single nesting. In the 1878 Petoskey nesting, observers estimated the number of netters alone at seven hundred, with an additional fifty teamsters working to haul birds to the nearest railroad station. (p. 67)

Like other businessmen, market gunners had to keep an eye on the bottom line. The goal of market gunning was to shoot the most birds, in the quickest time, with the least personal cost—all to increase the gunners profit margin. The resulting mass killings boggle the modern mind.

Before bag limits were established by law, market hunters (and not a few sport hunters) gunned down as many birds as they could before their arms got too tired, their guns too hot, or their ammunition too low. Few could match market hunter William Dobson’s tally of 509 ducks killed on the opening day of the 1879 season in Maryland. Dobson bested himself, however, shooting 529 ducks in 1884. In Illinois, Henry Kleinman recalled that shooting on the Calumet River brought him a one-day bag of more than two hundred teal. It took him no more than two hours and only sixty shells to make that record. Smaller songbird species that were commercially hunted, such as robins, bobolinks, and blackbirds, could also be harvested in impressive one day bags. The Sam Armstrong family at the head of Delaware Bay reportedly shoot between twenty-five and thirty dozen bobolinks in flight each day. Alone, Sam Armstrong could shoot as many as five hundred blackbirds on a good day. (p. 44)

Many more examples of these massacres are found throughout The Market in Birds.

What the market gunners used to make their mass killings varied. In the beginning it was just a whole lot of guns. But the semiautomatic shotgun was invented in 1900. Many market gunners used increasingly more powerful weapons like punt guns and even huge water cannons. On page 43 of The Market in Birds is a photograph of a small boat with a seven barreled 12-gauge battery of guns that could be fired at one time. Guns like this could kill 40-50 ducks in a single discharge.

At the same time there were also plume hunters decimating heron colonies on both coasts and the Gulf of Mexico and eggers who gathered eggs for the market. There was a growing market for the down from eiders, scoters, loons, swans, and geese for pillows, cushions, and bedding. There was even a market for specimens for museums, colleges, and collectors. Throughout all this killing, wildfowl populations were being pushed ever westward, but the West Coast was also a center for the market in birds. There was no place in America where the wildfowl seemed safe from the market gunners.

The whole “Great West” became the game dealer’s own “happy hunting ground.” (p. 120)

San Francisco-area market hunters plied the region’s estuaries, bays, and the vast wetlands of the Sacramento-San Joaquin river delta for abundant ducks and geese as well as the commercially popular California clapper rail (Ridgway’s rail). Gunners took down band-tailed pigeons along the Pacific coast range, and plume hunters and egg collectors invaded Pacific island seabird rookery. (p. 94)

The primary markets for wildfowl were high end restaurants and markets in large cities. It was not unusual at the time to go to your neighborhood butcher and find, in addition to the expected chickens and sides of beef, prepared carcasses of a wide variety of wildfowl, upland gamebirds, doves, and shorebirds. The menus of restaurants featured a crazy array of specialties made with the market gunner’s prey. Some of these recipes featured a European touch.

Chefs at Delmonico’s, New York’s premier restaurant during the market hunting era, were perhaps the most important contributors to the wild game mystique spreading across the fine-dining landscape in the late nineteenth century. Wild birds done up in the French tradition were always a major feature of Delmonico’s menus. Chef Charles Ranhofer’s encyclopedic cookbook The Epicurean (1892) contained an entire chapter on the preparation of game and an index listing what game was available in each season. Recipes such as “Blackbirds À La Degrange,” “Canvasback Ducks Roasted Garnished With Hominy” (which required Havre de Grace, Maryland, ducks), “Wild Pigeon or Squabs Poupeton, Ancient Style,” and “California Quails À La Monterey” revealed both a devotion to regional foods and the popular mixture of continental cooking with characteristically American ingredients that was the basis for the “Franco-American” culinary style. Dishes like “Plovers À La Victor Hugo,” “Partridges À La Jules Verne,” and “Salamis of Teal Duck À La Harrison” demonstrated Ranhofer’s penchant for naming dishes after famous personages, especially those that patronized Delmonico’s. Woodcock appeared to be a favorite of Ranhofer’s, since he created a dozen different recipes for the species including “Breasts of Woodcocks À La Houston. (p. 107–8)

Much of what fueled this interest in these dishes made with wildfowl was a passion for anything “wild.” Just as people today consider food labeled “organic” to be superior to food grown on unnatural factory farms, during the age of the market gunners food sourced from the wild was considered morally better and superior in taste.

In the market, wildness most often came packaged in avian forms. Biology and economy conspired to make wildfowl exceptionally salable, but it was wildness that made birds especially valuable to Americans. “All good things are wild and free,” wrote Henry David Thoreau at midcentury. For the modern consumer, though, only half that statement was true. The market in birds proffered the laudable qualities of wild Nature, but they were hardly free. (p. 119)

This viewpoint also led to the belief that recreational hunting was a superior avocation because it brought the hunter out into the purity of nature. As a result, the numbers of amateur hunters increased at the same time as the market gunners were active. “Equally destructive was the growing army of recreational wildfowlers. The modern ‘rage for hunting’ encouraged amateurs to pursue birds relentlessly, and new forms of transportation allowed them to do so.” (p. 121) Amateur hunters killed large numbers of birds too because there were no bag limits, but they considered themselves superior to the market gunners. “For recreational hunters, the critical difference between proper and improper wildlife use was profit seeking rather than expertise. Sportsmen made it clear that they never sold any game.” (p. 48)

The role of the amateur hunter in the eventual passing of state and federal legislation to regulate hunting is an interesting and subtle story. Smalley in The Market in Birds follows this evolution closely. It is an interesting tale because sportsmen hunters were exploiting wildfowl too, often shooting as many waterfowl as they could, but just not on the level of the market gunners. But they were finding their prey harder to find because of the market.

Sportsmen found exploitation far easier to identify when it occurred in the market. Confronting the apparatus of wildfowl commercialization directly, amateur hunters found allies among scientists, bird lovers, and politicians who sought national prohibitions on avian marketing. (p. 10)

Sportsmen hunters defined themselves as the true appreciators of nature versus those “evil” market gunners working for profit. The tropes of sportsmen hunters being closer to nature and therefore better at understanding nature more deeply than the non-hunter are still heard today. But there is no doubt that the vocal support of these amateur hunters helped get needed laws passed.

In the end, activist sport hunters succeeded in redefining what had been a respectable enterprise as an outmoded, mercenary practice of questionable legality. In this new narrative, the “market hunter” and the “Game dealer” were cast as villains. The sportsman, in his role as the “game protector,” was the hero. (p. 123)

It is interesting that the former market gunner Henry Clay Merritt found the amateur hunter just as much of a problem as the market gunner.

Amateur hunters were not governed by these kinds of rational cost-benefit calculations. The actual “value of game killed” by sportsmen was “often less than the cost of killing,” Merritt observed. While many previously “believed that the scarcer the game the less demand would be made upon it,” the “rage for hunting” had nevertheless continued unbated into the twentieth century. It had grown “beyond all reasonable bounds” even as wildfowl populations dwindled. “Where men hunt for sport,” Merritt claimed, the supply of game would continue to suffer “constant or yearly pursuit” as hunting enthusiasts chased after seemingly limitless cultural, social, and psychic intangibles sport hunting advocates promised. (p. 13)

Eventually, legislation including The Migratory Bird Treaty Act (1918) finally brought an end to the market gunning business locally and nationally. But it was not easy to get this act and other bills through Congress. Smalley traces these political arguments in detail in The Market in Birds. It would take pages more of this review to outline the political wranglings that Smalley documents in this book.

The Market in Birds is an outstanding contribution to the history of wildfowl migration and its intersection with American political and business forces. Though many of you are likely familiar with the tragic story of the exploitation of the Passenger Pigeon, Smalley reveals that was only one story of a much larger and more pernicious epic of the widespread commercialization of birds in America. The reader will also realize that wildfowl were once astonishingly abundant in many places across the country not that long ago. These impressive waterfowl numbers will likely never be seen again. After the market gunners took their toll, what followed was the rapid development of the country and the resulting destruction of much waterfowl habitat. This devastation was thanks in part to those same railroads and cars that aided those market hunters. The Market in Birds is a tragic story of what happens when wildlife is treated like commodity. It recounts an important part of the natural history of our country that is often ignored: a widespread bloodlust for killing wild birds inspired by market forces.

The main consideration was always to kill or capture the most birds with the least effort for the best price. Consequently, market hunting accounts routinely listed the amount killed in a single shot, a single day, or in a single season. A sense of competitive boasting sometimes accompanied the reports, many claiming to record the largest bags ever made. (p. 43)

To listen to Mark Lynch’s conversation with Andrea L. Smalley on WICN, click on this link: https://wicn.org/podcast/andrea-l-smalley/