Mark Lynch

FADE IN:

INT. A DARK AND MESSY ROOM LIT ONLY BY A GOOSENECK LAMP.

A disheveled unshaven man is furiously typing at his pc. The camera zooms in over his shoulder to read the title on the screen:

True Tales of Treating Traumatized Trochilidae in Tinseltown

CUE REVIEW:

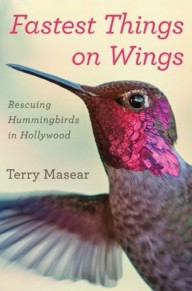

Fastest Things On Wings: Rescuing Hummingbirds In Hollywood. Terry Masear. 2015. Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Hooray for Hollywood

Where you’re terrific, if you’re even good

Where anyone at all from TV’s Lassie

To Monroe’s chassis is equally understood

Go out and try your luck, you might be Donald Duck

Hooray for Hollywood

(Doris Day’s interpretation of Johnny Mercer’s classic song “Hooray for Hollywood”)

A few decades ago I was leading a Mass Audubon birding class trip to Westport, Massachusetts. We were in Acoaxet when we came across an injured young Black- backed Gull. As birders, we frequently encounter injured birds. We may pause for a few heartbeats and bemoan the bird’s fate, but we quickly move on to the next stop, likely rationalizing something about “letting nature take its course.” But this time was different. One of my students worked at the Tufts University Wildlife Clinic in Grafton. Here they treat all manner of wildlife, often for free, doing their best to heal and then release the animal back into the wild. The woman from the clinic captured the gull with some difficulty, found a box to house it in the back of her car, and immediately left to bring it to the clinic. I hate to admit this, but my first reaction then was, “Well, it’s just a gull.” But the rehabber thought very differently. Her first reaction was to see if something could be done for the bird and if not, to humanely euthanize it. The bird had to go to the clinic right now. Everything else, such as the trip and her birding, was secondary. Weeks later, on a class trip, we released the gull, now healed. That incident changed me in a very fundamental way. I have since interrupted several trips to rescue birds and bring them to Tufts, and I never think to myself, “It’s only a gull” or “It’s only a sparrow” or even “It’s only a starling.” It’s a life and I can do something helpful here.

People who rehabilitate wildlife live very different lives from the rest of us. It is nothing short of a calling for them, and their dedication can at times appear insane. While reading Fastest Things On Wings, there were times when I wasn’t sure whether Terry Masear deserved a medal or meds, or both. The book starts innocently enough:

If destiny arrives at times by chance and at other times by choice, for me it came through some of each. In my case, the future appeared in the form of a pinfeathered hummingbird washed out of his nest in the ficus tree just outside our house during a punishing rainstorm. (p. xi)

When Terry was successful in getting that hummingbird to adulthood and flight, she thought that this might be something she would enjoy doing. She had no idea what she was in for, and soon she found herself deep into the crazy life of a rehabber. Just a few pages into Fastest Things On Wings, readers will likely remind themselves to be careful what they wish for. To date she has rescued more than 5000 hummingbirds in the greater Hollywood area and has fielded over 40,000 calls day and night from a variety of humanity. This includes the classic Hollywood types, super rich and spoiled people “in the business” who suffer a surfeit of what Terry calls “unenlightened self-interest.” But she has also dealt with the other, seedier side of Hollywood: “I’ve taken in birds from drug dealers, gangbangers, the morally bankrupt, the criminally insane, and other degenerates lingering on the periphery that nobody has bothered to report.” (p. 72)

When Terry was successful in getting that hummingbird to adulthood and flight, she thought that this might be something she would enjoy doing. She had no idea what she was in for, and soon she found herself deep into the crazy life of a rehabber. Just a few pages into Fastest Things On Wings, readers will likely remind themselves to be careful what they wish for. To date she has rescued more than 5000 hummingbirds in the greater Hollywood area and has fielded over 40,000 calls day and night from a variety of humanity. This includes the classic Hollywood types, super rich and spoiled people “in the business” who suffer a surfeit of what Terry calls “unenlightened self-interest.” But she has also dealt with the other, seedier side of Hollywood: “I’ve taken in birds from drug dealers, gangbangers, the morally bankrupt, the criminally insane, and other degenerates lingering on the periphery that nobody has bothered to report.” (p. 72)

It seems that everyone, no matter where they reside on society’s ladder, loves hummingbirds, and when they find one in trouble, there is an impulse to do something to help the tiny waif. Often, however, that impulse is horribly executed. For instance, Terry has taken in nestling hummingbirds that people have previously fed “...prune juice, Gatorade, protein powder, soda pop, wheat bread, boiled eggs, Fig Newtons, and in one bizarre instance, breast milk.” (p. 114) None of these is good for young hummingbirds and may kill them. But Terry takes in these birds and does her best to heal them and send them on their way.

As you can imagine, rehabilitating hummingbirds is a tremendous amount of intensive work. “Most wildlife centers won’t even let them through the front door. Every rehabber will tell you that immature hummingbirds are the most demanding, high maintenance, and stress inducing birds under the sun.” (p. 51)

There are never-ending feedings. Just getting the over-ripe bananas used to grow and feed the fruit flies that hummingbirds need is a chore that most of us would bail on after a few weeks. There are special procedures like “crop siphoning” that have to be done if the original hummingbird finder stuffed a bunch of ants (or worse) down the hummingbird’s throat. Running through the book are long and complicated stories of the difficult recuperation of two hummingbirds named Gabriel and Pepper.

Each hummingbird has an individual personality. As it graduates to a larger cage in which it can relearn to fly, there can be frightening fights that lead to more damage and setbacks. Terry’s charges need almost constant monitoring. Some of her hummers have complicated problems like neural damage or injured wings or have been traumatized by their injury or a run-in with a predator. Such cases have to be dealt with uniquely and even more intensively than usual. There are several times in Fastest Things On Wings when the reader gets empathetically exhausted for Terry. Amazingly, injured or distressed hummingbirds just keep coming, and Terry just keeps going. It seems positively Sisyphean. Compassion fatigue is a constant problem for rehabbers. This happens because there are times when the hummingbird dies despite Herculean efforts. It’s always heartbreaking, and the emotional toll of those losses can be devastating. This is yet another sacrifice rehabbers make when they take on the awesome responsibility of healing wild creatures; when those creatures die, the rehabber takes the pain. In the worst of times Terry uses her martial arts training and interest in the Tao Te Ching to center herself. Such times seem to occur every other week.

You don’t have much of a social life during the many months when hummingbirds are breeding. You don’t get much sleep, and you eat poorly, when you eat at all. At one point in Fastest Things On Wings Terry comes down with a horrible flu and collapses but manages to get back in the game after too short a time because she has to. There are other hummingbird rehabbers in the area, most notably Jean Roper, but they are also stressed from taking in as many birds as Terry. Jean Roper is the seasoned veteran rehabber that Terry often turns to when something new or challenging comes up, but Jean is often even busier with more hummingbirds than Terry.

The variety of species Terry Masear has rehabilitated is impressive. Allen’s, Anna’s, Black-chinned, Broad-tailed, and Rufous all now nest in the greater Los Angeles area, though the last two species are relatively recent nesters there. All of them have gone though Terry’s clinic. Occasionally a Calliope or a Costa’s shows up. It is no exaggeration to call Los Angeles and Hollywood the hummingbird rehab capital of North America. Why are there so many hummingbirds in such an urban area? Because all those wealthy Hollywood homes have numerous flowers and other plantings for hummingbirds to feed on and nest in, and numerous pools and fountains provide sources of water. Conspicuous wealth can be great for certain species. But it can be a double-edged sword, as a number of the nestling hummingbirds brought to Terry were found after gardeners have trimmed foliage and bushes in upscale yards and inadvertently chopped down a nest. Other birds have flown into limos or are covered with mites. Every call or knock at the door is a different tale of hummingbird woe. And they just keep coming. Some people are in tears and are looking for assurance that the hummingbird will be all right. Others just want the responsibility gone as quickly as possible and for Terry to assuage their conscience by taking the bird off their hands. Other people try to dump non-hummingbirds off at her clinic, everything from a flock of ducklings to a young bobcat. The thought is simply that because she rehabs one thing, she can and has the time to rehab anything.

Throughout Fastest Things On Wings, Terry Masear shares her considerable hard- earned knowledge about the lives of hummingbirds. For instance, did you know that experienced hummingbird rehabbers can often identify the species of hummer just by looking at the color of the nest? Or that hummingbirds often exhibit a death-like torpor in response to extreme physical stress? They may look dead, but there may still be hope. Fastest Things on Wings offers a wealth of information on the behavior and anatomy of western species of hummingbirds that will be new to most birders.

Fastest Things On Wings is a classic, a must-read book for anyone who enjoys hummingbirds. Ultimately, this is a book about the natural world and how humans interact with it and think about it. It is a book about the responsibility all of us have, trying to live with the natural world instead of just ignoring it. It is also a reality check for anyone who has thought that being a wildlife rehabilitator would be a fun and easy job. The job certainly has its rewarding moments, but you more than earn those moments. I had the pleasure of interviewing and talking with Terry Masear not long ago. She was a down to earth, very centered person with a great sense of humor. We laughed a lot about who would play her should this amazing story ever get the full Hollywood treatment. But in the end I still don’t know how she does what she does. After reading Fastest Things On Wings, I certainly know why she does it.

The author stops typing, tiredly looks at screen and, shrugging, hits “Save” and shuts off his PC. He gets up and leaves the room to get a beer.

FADE OUT.

CUE END MUSIC AND ROLL CREDITS.