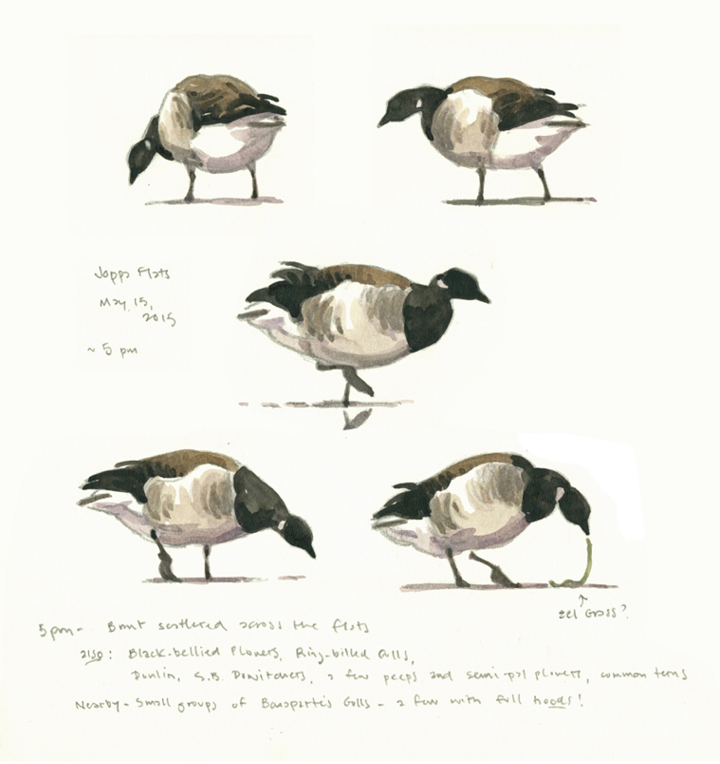

Brant by Barry Van Dusen

Brant by Barry Van Dusen

An artist who has created many of our covers, Barry Van Dusen lives in Princeton, Massachusetts, and is well known in the birding world. Barry has illustrated several nature books and pocket guides, and his articles and paintings have been featured in Birding, Bird Watcher's Digest, and Yankee Magazine as well as Bird Observer. Barry's interest in nature subjects began in 1982 with an association with the Massachusetts Audubon Society. He has been influenced by the work of European wildlife artists and has adopted their methodology of direct field sketching. Barry teaches workshops at various locations in Massachusetts. For more information, visit Barry's website at http://www.barryvandusen.com.

Brant

The Brant (Branta bernicla) is a goose that breeds in the low and high Arctic, migrates long distances, and winters primarily in coastal areas throughout the Northern Hemisphere. It is a relatively small dark goose with a short neck and a small bill and head. It has a distinctive black head, neck, and breast. The neck is highlighted by a series of white striations that form an incomplete necklace in eastern populations. The wings are grayish brown except for black primaries. Belly color varies from light gray to black in different subspecies. In lighter birds, the flanks are darkly streaked. Males are on average larger than females and young birds resemble adults, however they lack the white neck striations and have prominent white feather edgings to the wing coverts. The lack of a white cheek and throat patch separates Brant from the larger Canada Goose.

The Brant is divided into three subspecies, B. b. bernicla, B. b. hrota, and B. b. nigricans, although some researchers lump bernicla and hrota into one species and separate nigricans into a second. The taxonomy of this group requires further resolution. Subspecies hrota includes the light-bellied Brant that breed in the low to high Arctic of Canada and in northern Greenland; they winter along the East Coast of the United States and as far east as Ireland. Subspecies bernicla is dark bellied, breeds in the Russian Arctic, and winters in Western Europe. Subspecies nigricans, which is often referred to as the "Black Brant," has a black belly, breeds in the Arctic of western Canada and Alaska to Russia, and winters from southern Alaska in coastal patches south to Baja California and northwestern Mexico. Coastal wintering areas are generally distinguished by the presence of sea grasses (e.g., eel grass) and marine algae (e.g., sea lettuce).

In Massachusetts, the Brant is considered a locally abundant winter resident and migrant. They leave their Arctic breeding grounds in early September and form large flocks in staging areas in James Bay, Canada. There, they fatten up for their long nonstop flights to their East Coast wintering grounds, typically arriving each year in November and December. They head back to their breeding grounds in April and May. Brant numbers in Massachusetts decreased from the thousands in 1930 to less than a hundred a few years later, following an eel grass blight in 1931 that functionally eliminated their main food supply. They have steadily increased in numbers since then.

Brant are generally monogamous and usually mate for life. However, extra-pair copulations are not uncommon. They breed at two to four years of age. Both males and females utter a guttural cronk. Males are aggressive during territorial establishment and pairs will chase intruders. Both sexes use a threat posture—head held forward and low and bill open—and defend the area around their nest. On staging and wintering grounds, pairs may defend a feeding territory. Goslings stay with their parents through winter and spring. In nonbreeding season, Brant are gregarious, sometimes forming flocks of several thousand birds. Brant generally do not form mixed-species flocks but may form nesting colonies with other species including gulls, and surprisingly, Snowy Owls.

In the low Arctic, Brant nest in colonies at the upper edge of salt marshes, often on islands, ponds, or deltas. The nests are usually exposed and in short grass. In the high Arctic Brant nesting is more dispersed along river valleys, lakes, and braided streams. Brant are colony-site faithful and sometimes return to the same nest site. The female constructs the nest of grass and other vegetation, which she forms with her breast and feet. Enough vegetation is included to allow covering the eggs when she leaves the nest. The nest is lined with down. Only the female develops a brood patch, and she alone incubates the usual clutch of three to four buff or creamy white eggs tinged olive for the 23–24 days until hatching. Both parents defend their nest against predators, including foxes, and they regularly chase off marauding gulls, ravens, and jaegers. The young are precocial with eyes open at hatching, and they are covered in down. By the end of their first day, they can leave the nest, walk, swim, and feed. The parents accompany the goslings away from the nest and the female broods them for the first two weeks. The young can fly in about six weeks and eventually the young accompany the parents to the staging and wintering areas.

Brant forage along inter-tidal mud flats feeding on eel grass, green algae, and intertidal salt marsh plants. In some wintering areas they also graze upland grasslands, including golf courses and athletic fields. They forage while walking or by dipping or tipping up while swimming. Their diet varies among seasons. Brant have well-developed salt glands and thus can drink salt water, although they generally prefer fresh water.

Brant may experience nesting failure due to extreme spring weather events, flood tides, or nest predation by gulls and jaegers. Adults and young are subject to predation by Snowy Owls, foxes, wolverines, coyotes, and grizzly and polar bears. Human intervention is a major factor in affecting population size. In Alaska, gathering of eggs and flightless Brant by Yupik people is historically important, as is spring and summer hunting by the Cree in James and Hudson bays. Large numbers of Brant are killed in fall hunting on both coasts of the United States. Industrialization has also reduced eel grass communities. The numbers of Brant wintering on both United States coasts declined during the second half of the 20th century, but cooperative management plans involving the United States, Canada, and Mexico have helped stabilize the populations, although there are substantial fluctuations from year to year. This provides some hope that this delightful little goose will winter along our coasts indefinitely.

William E. Davis, Jr.