Cory R. Elowe, Sam McGullam, Meghadeepa Maity, and Jeremy A. Spool

Birding is considered by many to be a particularly accessible activity. With the bare minimum of equipment or experience, anyone can in theory enjoy birds—from their own backyard to pristine forests or busy city centers. During the Covid-19 pandemic, with increased focus on outdoor, solitary, and home-based activities, interest in birding has skyrocketed (Fortin 2020). But birding is also an activity that historically has been dominated by an older, wealthier, white population. Expanding diversity and inclusion have become important topics for bird clubs around the world (Carver 2013), but each of us, no matter our level of birding experience or ties with established birding communities, can contribute to a more inclusive outdoors. In Massachusetts, to achieve this end we have developed an open-access tool called The Murmuration, a Google Spreadsheet where contributors provide details about popular birding hotspots, with the ultimate goal of eliminating the barriers to local knowledge and encouraging new birders of all backgrounds to safely explore birding.

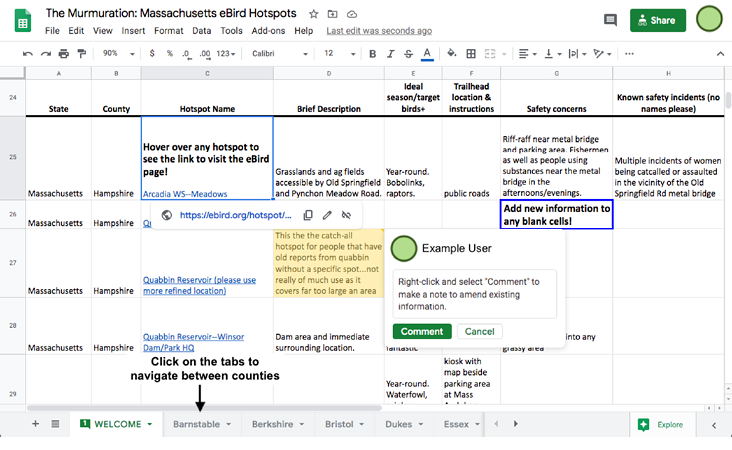

Figure 1. A subset of information available in The Murmuration. Hotspot names include links to corresponding locations on eBird.org. There are separate tabs in the spreadsheet for each county in Massachusetts. Empty cells can be populated with information, and comments on existing cells alert moderators to information updates.

Isn’t birding already inclusive?

Enjoyment of outdoor activities is a privilege that many people take for granted. In May 2020, a widely reported incident in Central Park provided a sobering example of how birding and being outdoors are not safe activities for many people. This incident, captured in a video that went viral, showed a white woman attempting to weaponize her privilege with the police against a Black birder, Christian Cooper, after he requested that she obey leashed-dog requirements. In response, the newly formed collective BlackAFinSTEM organized Black Birders Week, during which people shared hundreds of experiences like Christian Cooper’s and worse—showing us in no uncertain terms that this was not an isolated occurrence (Thompson 2020).

Marginalized groups have been excluded not only from the act of birding itself, but also from stewardship of land and nature in areas such as urban planning, climate policy, and environmental practices (Schell et al. 2020). This exclusion impedes conservation efforts and citizen science—or community science, to be inclusive of immigrants—through unequal demographic participation. As one of the most valuable and widespread tools for community science, eBird data support conservation action and help birders explore sightings and population trends (Sullivan et al. 2009). However, because the data are contributed by a narrow subset of the population, we have an inaccurate picture of our natural landscapes and bird communities (Perkins 2020). Valuable voices and perspectives from those in marginalized communities are missing from our efforts to protect and conserve the birds we all love.

Many bird clubs and other organizations have already taken action by focusing on recruiting diverse individuals. But there’s a catch: the business world has repeatedly shown that pursuing diversity simply to increase numbers without inclusion—that is, the authentic empowerment of underrepresented groups—can negatively affect diversity (Sherbin and Rashid 2017). Ted Lee Eubanks, founder of Fermata Inc., noted that “We should focus on developing new ways of helping non-traditional populations find their way to nature through birds, and we should worry less about how they might then mold that interest into a meaningful recreational pursuit” (Robinson 2007). Our efforts would be best spent removing as many barriers as possible to enable new birders to explore in their own way, starting with open access to a vast amount of local birding knowledge.

Black Birders Week made it clear that a rich and vibrant community of Black birders is growing, but centuries of systemic racism are not easily undone, and outdoor spaces are still the domain of white people (Walker 2019). In his book The Home Place: Memoirs of a Colored Man’s Love Affair with Nature, Dr. J. Drew Lanham exhorts readers to “Get more people of color ‘out there.’ Turn oddities into commonplace.” (2016) Many birders believe in inclusion and want to share their love of birds with everyone, but to make birding truly accessible we need to take active steps in our own communities to open the outdoors to those with different identities or backgrounds.

Birding knowledge, unlike birds, does not migrate

Birders are often reluctant to share information that may increase traffic to favorite birding locations, but this can uphold and strengthen barriers to new participation by historically excluded groups. Greater access to this information is not at odds with conservation goals and does not necessarily lead to overcrowding of hotspots, as some may fear. Instead, shared information may encourage birders to disperse away from well-trafficked hotspots and explore new areas.

New tools online have already made great headway in expanding access to birding information. It used to be that people got wind of birding spots and knowledge through personal contacts, bird clubs, and phone trees, or through flyers, booklets, and other guide documents published by local communities and organizations. Now, online resources like eBird and other user-friendly birding apps help just about anyone look for and identify birds in their area.

However, without easy access to local expertise, new birders and birders of marginalized identities still face confusion, discouragement, hostility, and danger in the field. eBird hotspots—the most popular and highly visited birding sites in a region—are frequently on or adjacent to private property, require permission to access (without clear landowner contact information), or simply provide a GPS point in a nondescript forest that leads to cryptic trailheads or access points. For birders with disabilities and mobility concerns, many trails and viewpoints are inaccessible, and information about trail conditions and handicap accessibility is difficult to find. Hotspots may also have a history of safety incidents, including confrontations with owners of neighboring properties, assaults, and police harassment, all of which would be useful to know when searching for new places to go birding.

This lack of transparent information is particularly daunting for those who already do not conform with the public’s image of the traditional American outdoor enthusiast. We all know of a birding spot where word-of-mouth instructions are simply to stroll past the “No Trespassing” signs, but this can be uncomfortable, if not dangerous, for some people. If we ensure that local wisdom spreads its wings beyond a few veteran birders who are active within established bird clubs, we increase the accessibility and safety, and therefore inclusivity, of birding across a broader landscape.

The Murmuration: a tool to spread birding knowledge

Crowdsourcing, like communication in flocks of birds, has the potential to spread the rich but tightly held knowledge in our birding communities. To begin crowdsourcing local birding hotspot information, we compiled the top 100 eBird hotspots for Massachusetts counties into a Google Spreadsheet called The Murmuration. For any birding spot in your area, you can add a variety of area/trail descriptions, accessibility information, and safety concerns (Figure 1).

The Murmuration is open access, which means that anyone with a link can access and edit the document. So how do you start? Like birding, it can be as easy or as involved as you want it to be.

From the Welcome screen, navigate to your county of choice via the spreadsheet tabs. (You will notice that some tabs are sparsely populated—that is where your contributions are needed the most!)

eBird hotspots are listed in alphabetical order for each county. If you hover over any hotspot name, you will see a link to visit the corresponding page on eBird.org.

For each hotspot, there are a number of different fields that users can populate with information. As of October 2020, these include: a general description of the trail; trailhead instructions; ideal seasons or species; safety concerns and known incidents; whether it is private property and, if available, contact information for access permission; and descriptions of parking and trail conditions that are especially informative for people with disabilities and mobility issues.

Fill in as much information as possible for any given hotspot, without altering previous participants’ work. Instead, submit comments (using the “Insert comment” command) when a clarification or update to a field is needed; a volunteer editor will incorporate your update into the existing listing.

By allowing anyone to propose edits, we ensure that updates are continuous and misinformation can easily be identified and corrected, and that information about hotspots will become richer and can be modified when conditions change (e.g., to reflect trail closures or overcrowded conditions during the Covid-19 pandemic). This also means that people with different experiences at a hotspot will be able to add their experiences to the document and fill in gaps where needed. For example, a non-disabled person may not be proficient at gauging handicap accessibility, and many men are not conscious of the fears that women may feel in isolated areas. Thus, The Murmuration reflects the expertise of the entire community rather than that of specific individuals, allowing for a mutual exchange of perspectives from people of different identities. Furthermore, by crowdsourcing the descriptions of local birding hotspots while emphasizing issues of safety and accessibility, the birding community can challenge assumptions about what the “traditional” American outdoor enthusiast looks like and reduce barriers to equitable access (Maldonado 2020).

This document will undoubtedly evolve as new needs arise and may serve as a template for communities around the country and beyond. While accessibility and navigation of the sheet are currently not optimal for all users, this simple database has boundless potential and scalability. It can be shared widely where it is most needed, browsed in its current format, or exported and refined for more accessible viewing. The electronic format can, with relative ease, be converted to large fonts, dyslexic script, audio formats, and Braille, and may appeal more broadly than a physical document to people of various abilities and preferences. Local organizations can host the nascent spreadsheet or use it to curate regional guides and resources. The information can be submitted to other online platforms, such as the National Audubon Society’s Birdability project (Todd and Hobbs 2020), to expand upon the current database of accessible birding locations. Or, this spreadsheet may serve as the basis for some as-yet-unrealized project for an ambitious birder with programming experience. Ultimately, the data collected may even find a home on eBird, directly associated with the birding hotspots and managed by regional moderators or a specific volunteer database manager. Whatever the final product may be, public input is crucial to ensure that those whose perspectives are overlooked can have their voices heard, and The Murmuration will serve an additional purpose as a database of progress toward equitable outdoor access.

Great! But I’m only one person. What can I do?

First, tell other bird lovers about The Murmuration; the more people who have access to this database, the more comprehensive and accurate it will be. Post it on your local bird club’s social media page or call your favorite birding buddy. Then the next time you go birding at an eBird hotspot, take a look at the spreadsheet for your local county and see what information is available. If there are blank spaces, try to pay attention to the gaps during your visit. Are there safety concerns? Do the trail conditions change after a hard rain or snow? Once you get home, click on the link and update that information. If you are stuck at home on a snowy day, spend ten minutes browsing the sheet and see whether you can fill in any holes. Maybe all of your usual hotspots are completed? Browse the information and see whether there is anything you can suggest to increase its accuracy, or see what you learn from other people’s contributions to broaden your own perspective.

This is a team effort, so every contribution makes a difference in enhancing the safety and accessibility of birding. With many contributors we can create a useful resource for anyone to learn more about these hotspots, eliminate barriers for both new and veteran birders of all identities, and bridge gaps in our knowledge with the inclusion of diverse viewpoints. We are excited to work alongside the Association of Massachusetts Bird Clubs and other partners to develop this resource and empower each community to share responsibility in providing accurate, timely updates. It is this seamless transfer of information that will keep the whole flock together.

References

- Carver, E. 2013. Birding in the United States: A Demographic and Economic Analysis; Addendum to the 2011 National Survey of Fishing, Hunting, and Wildlife-Associated Recreation. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Available online at <https://www.fws.gov/southeast/pdf/report/birding-in-the-united-states-a-demographic-and-economic-analysis.pdf> Accessed October 14, 2020.

- Fortin, J. 2020. The Birds Are Not on Lockdown, and More People Are Watching Them. The New York Times. Available online at <https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/29/science/bird-watching-coronavirus.html> Published May 29, 2020; accessed September 27, 2020.

- Lanham, J. D. 2016. The Home Place: Memoirs of a Colored Man’s Love Affair with Nature. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Milkweed Editions.

- Maldonado, M. 2020. Modern Land Stewardship Requires a Modern Philosophy. LinkedIn. Available online at <https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/modern-land-stewardship-requires-philosophy-marcela-maldonado/> Published July 29, 2020; accessed September 30, 2020.

- Perkins, D. J. 2020. Blind Spots in Citizen Science Data: Implications of Volunteer Bias in eBird Data. MS dissertation. Fisheries and Wildlife Conservation Biology, North Carolina State University. Raleigh, North Carolina.

- Robinson, J. C. 2007. Birding for Everyone: Encouraging People of Color to Become Birdwatchers. Marysville, Ohio: Wings-on-Disk.

- Schell, C. J., K. Dyson, T. L. Fuentes, S. Des Roches, N. C. Harris, D. S. Miller, C. A. Woelfle-Erskine, and M. R. Lambert. 2020. The ecological and evolutionary consequences of systemic racism in urban environments. Science 369 (6510): <https://science.sciencemag.org/content/369/6510/eaay4497> Accessed October 14, 2020.

- Sherbin, L. and R. Rashid. 2017. Diversity Doesn’t Stick Without Inclusion. Harvard Business Review. Available online at <https://hbr.org/2017/02/diversity-doesnt-stick-without-inclusion> Published February 1, 2017; accessed September 27, 2020.

- Sullivan, B. L., C. L. Wood, M. J. Iliff, R. E. Bonney, D. Fink, and S. Kelling. 2009. eBird: A Citizen-Based Bird Observation Network in the Biological Sciences. Biological Conservation 142 (10): 2282-2292.

- Thompson, A. 2020. Black Birders Call Out Racism, Say Nature Should Be for Everyone. Scientific American. Available online at <https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/black-birders-call-out-racism-say-nature-should-be-for-everyone/> Published June 5, 2020; accessed September 29, 2020.

- Todd, E. and R. Hobbs. 2020. Birdability. Available online at <https://tinyurl.com/birdability> Accessed October 14, 2020.

- Walker, J. 2020. Lions and Tigers and Black Folk, Oh My! Why Black People Should Take Up Space in the Outdoors. Melanin Base Camp. <https://www.melaninbasecamp.com/around-the-bonfire/2019/4/10/why-black-people-should-take-up-space-outdoors> Published April 11, 2019; accessed September 24, 2020.

Cory Elowe is a PhD Candidate studying migratory bird physiology in the Organismic and Evolutionary Biology program at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. He received his MS in Biology at California Polytechnic State University in San Luis Obispo. He has been an avid birder and outdoor enthusiast for many years and is a member of the Hampshire Bird Club and vice president of the UMass Grad Bird Club.

Sam McGullam is a medical editor, birder, and lifelong student of natural history. They received their BA in English from Middlebury College in Vermont. Originally from Long Island, they now haunt the woods of Northampton, Massachusetts, where they are a member of the Hampshire Bird Club.

Meghadeepa Maity grew up birding in India and is continually perplexed by the American indifference to white privilege. She serves on the Education Committee of the Hampshire Bird Club and facilitates the local Anti-Racist Collective of Avid Birders. When she is not in school or birding, she can be found participating in radical mental health initiatives or playing with a West African drumming ensemble.

Jeremy Spool is a postdoctoral research fellow studying the neuroscience of animal communication at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. He is a co-founder of the Massachusetts Young Birders Club and serves on the Education Committee of the Hampshire Bird Club. He’s always looking for pockets of time to get outside, binoculars in hand.