William E. Davis, Jr.

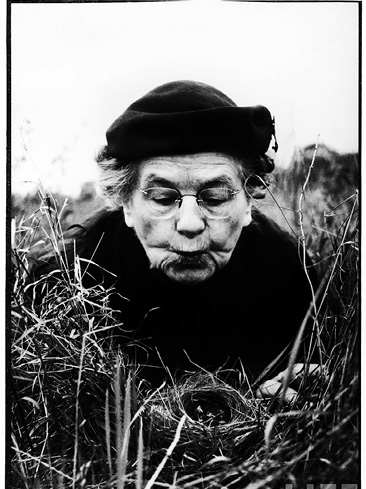

Figure 1. Margaret Morse Nice peering into a sparrow nest and talking to the young birds. Photograph by Al Ness, Life, September 10, 1956.

Margaret Morse Nice was born Margaret Morse on December 6, 1883, in Amherst, Massachusetts, into an academic family. Her father was a professor of history at Amherst College. The year of her birth was the same year as that of the American Ornithologists' Union (AOU), which she was destined to influence heavily. In her early years, Amherst was a rural town and her family took advantage of this by roaming the countryside and mountains of the area. Her mother had learned botany at Mount Holyoke College and her father was fond of the outdoors, so at an early age Margaret learned of the plants and animals of the region.

At the age of nine, she began keeping a written record of the birds she encountered. Her first entry was, prophetically, about a Song Sparrow, a species that eventually brought her fame. In her autobiography she records, "The most cherished Christmas present of my life came in 1895—Mabel Osgood Wright's Bird-Craft." (Nice 1979) At Amherst High School she took courses in mathematics, Latin, Greek, and French, starting her on a path that was to rely heavily on skill in foreign languages. As a teenager, Margaret studied the interactions of a dozen chickens that the family kept and established the concept of ‘pecking order' that was not to reach the scientific literature for decades. She began college at Mount Holyoke in 1901, which was interrupted by a year in Europe where she increased her skill in several European languages.

After graduating from Mount Holyoke, Margaret entered graduate school at Clark University in Worcester, which she recalled as very important in her development as a scientist: "It was at Clark University that I found purpose in life. Dr. Hodge, Dr. Hall, and my fellow students showed me that the world was full of problems crying to be solved; at every turn there was a challenge—nature waiting to be studied and understood." (Nice 1979) Her study at Clark of the feeding of a captive population of Northern Bobwhites launched her on a scientific research career with birds. She planned to use an expanded bobwhite feeding study to get a Ph.D. But instead, as she recalls: "These plans were changed. Instead of raising bobwhites, I was married; instead of working for a Ph.D., I kept house." (Nice 1979) In 1909, she married Leonard Blaine Nice who was an instructor in physiology. Her parents had opposed her engaging in doctoral studies and the societal norms of early 20th century America were not conducive to women getting Ph.D.s. She did, however, join the AOU in 1907, attending several annual meetings where she met the important ornithologists of the early twentieth century. However at the 1908 meeting, William Brewster gave a reception for the men attending the meeting while the women were invited to a separate reception. Nice commented: "Evidently, the role of the ladies was expected to be largely ornamental." (Nice 1979)

For the next decade, Nice turned her research activity to the study of speech development in her own five daughters and other children. Her papers on the subject earned her the M.A. from Clark University that she had not gotten for her bobwhite work. This work involved reading literature in French and German and working with mathematical analysis, all skills that would serve her well in her future ornithological work. During this child-raising period she published 18 papers on child development. As the children grew older and Nice became frustrated with the constraints of raising a family, she once again turned her attention to birds: "Relief came through three channels: my finding birds again; Eleanor's [her youngest child] growing out of babyhood; and in the spring of 1920 our purchase of an ancient car." (Nice 1979) The Nices had moved to Norman, Oklahoma in 1913, but spent their summers elsewhere. In 1919, they decided to spend the summer in Oklahoma and Nice re-entered the world of birds.

The proximate cause for this shift was her opposing the state changing the date of hunting season to include August, a month in which Nice knew that Mourning Doves were still nesting. She wrote letters and created a ruckus, documenting active Mourning Dove nests in Norman through October. This study of Mourning Dove nesting awakened in Nice an interest in all birds. Throughout her career, Nice wrote letters to editors of newspapers, primarily on conservation concerns. In one case she encountered a hunter with three Franklin Gulls he had shot: "He explained that he thought they were ducks, and that he had to ‘shoot things' to find out whether or not they were game birds. After reporting this ‘ignoramus,' Margaret wrote a letter to the Daily Oklahoman, ‘What is a Game Bird?'" (Ogilvie 2018)

At the 1920 AOU meeting in Washington, D.C., Nice presented a paper on nesting Mourning Doves in Norman and got substantial encouragement and direction from several prominent AOU members. In 1922, Nice embarked upon writing a book on the birds of Oklahoma and published the first of a series of papers on Mourning Dove nesting in The Auk (Nice 1922, 1923), her first papers on birds since her 1910 paper on bobwhite food. These two papers were important because of the large sample sizes. In 1919, she had located 37 nests on the University of Oklahoma campus; in 1920, 124 nests, and in 1921, 122 nests—numbers that were great enough so that statistical analysis could be employed.

In 1924, Nice, together with her husband, published The Birds of Oklahoma. They had traveled extensively throughout Oklahoma doing research for this book and the development of a conservation perspective is evident throughout: "… Such has been the effect of man's occupation—of the tilling of the land, of unwise meddling with nature and most of all, mere wanton destruction." (Nice and Nice 1924) The emergence of her career in ornithology was underway. She expanded the book considerably for a revised edition that was published in 1931 (Nice 1931d).

In the summer of 1925, Nice and her family visited relatives in Amherst, Massachusetts, and she took this occasion to study nesting of the Magnolia Warbler (Nice 1926). She did a survey of the birds of the region and published a paper on the changes that had occurred in the bird population in the 20 years since she had last studied them there (Nice 1925). In 1927, the Nice family moved to Columbus, Ohio, and settled into an undeveloped wild area that proved to be rich in bird life. Nice attended both the AOU and a joint Wilson Ornithological Club/Inland Bird-Banding Club annual meeting that year, renewing friendships and making new friends.

In 1928, Nice banded a Song Sparrow near her house, an individual she appropriately named Uno, and so began the most important study of her career. She also had a flurry of observations of other birds that produced papers on the nesting of Yellow-crowned Night-Herons, Blue-gray Gnatcatchers, Black-throated Blue Warblers, and Ovenbirds (Nice 1929, 1930a, 1931a, 1932a). Her long hours of observation were paying dividends. Her Song Sparrow nesting studies continued; she used Fish and Wildlife Service aluminum bands supplemented with unique color combinations of celluloid bands making possible individual recognition in the field. The sample sizes in the Song Sparrow research near her home in Ohio were large. In 1930, for example, she banded 47 adult Song Sparrows, found 61 nests, and banded 102 nestlings. Each year she compiled statistics on life histories of these color-banded birds, discovering, for example, that about half the birds migrated south for the winter and about half were year-round residents. She followed her Song Sparrows near home for the better part of eight field seasons compiling a veritable mountain of data. Again the papers began to flow (e.g., Nice 1930b, 1931b, 1932b).

In 1931, Nice attended the AOU meeting in Detroit, Michigan and there met Ernst Mayr, who was attending his first AOU meeting. Their meeting developed into a professional friendship that was to strongly affect Nice's career and enhance the practice and status of American ornithology. I interviewed Ernst Mayr in 1996 and he had a lot say about meeting Nice and the practice of ornithology in America at that time:

I attended my first AOU meeting in 1931 in Detroit … I was appalled at the program. … There was hardly a paper in the whole lot that dealt with the details of a life history study, a courtship display, anything like that. … I was appalled and I remember at that meeting I was so disgusted with the absolute vacuousness of the papers that I went over to the library of the Museum of Zoology in Ann Arbor to read the current literature. There was one other person there, a lady, and I introduced myself. She had a name tag on so I knew she was a member of the AOU It was Mrs. Nice. That's where I first met her. She had the same experience. Appalled at the emptiness of that program, she also went to the library. That was the nature of the difference between the European and the American ornithology.

That Nice shared Mayr's assessment of American ornithology at the time is indicated by a letter she wrote to West Coast ornithologist Joseph Grinnell in 1932:

Too many American ornithologists have despised the study of the living bird; the magazine and the books that deal with the subject abound in careless statements, anthropomorphic interpretations, repetition of ancient errors and sweeping conclusions from a pitiful array of facts. (quoted in Ogilvie 2018)

By 1933, she had begun to make an impression on her American colleagues and was invited to include a paper on territorialism in the AOU's 50th anniversary volume (Nice 1933a).

The Song Sparrow research is published

In 1932, Nice and her family visited Europe and one of the goals of that trip was for Nice to meet with European ornithologists. The highlight of this effort was meeting perhaps the most prominent European ornithologist of the time, Erwin Stresemann, and his student Ernst Mayr (whom she had met the previous year) who was visiting Stresemann from the United States. She worked for 10 days in Stresemann's library (Nice 1979), putting her language skills to work learning the European ornithological literature. Nice discussed her Song Sparrow study with Stresemann and complained to him about the difficulty of getting long papers published in American journals. Stresemann invited her to send him, as editor of the Journal für Ornithologie, the world's oldest ornithological journal, her manuscript on the Song Sparrow research. Nice's long paper was published in two parts, in German, in 1933 and 1934. Nice received a letter from Ernst Mayr that read: "I consider your Song Sparrow work the finest piece of life-history work, ever done."

Mayr also offered to arrange publication of an expanded and complete version of Nice's voluminous Song Sparrow research by the Linnaean Society of New York. It was published as two volumes (Nice 1937, 1943). The first volume, a population study of the Song Sparrow, was dedicated to Ernst Mayr who had served as an inspiration and friend. The reviews of this volume were laudatory:

In its form, this book is a model of clarity; in its substance, it is perhaps the most important contribution yet published to our knowledge of the life of a species. (Delacour 1937)

… a fundamental and original study of how birds live, worked out in the field in terms of one species, but checked and illuminated by frequent references to work on the same problems with many species in many countries. (Nicholson 1937)

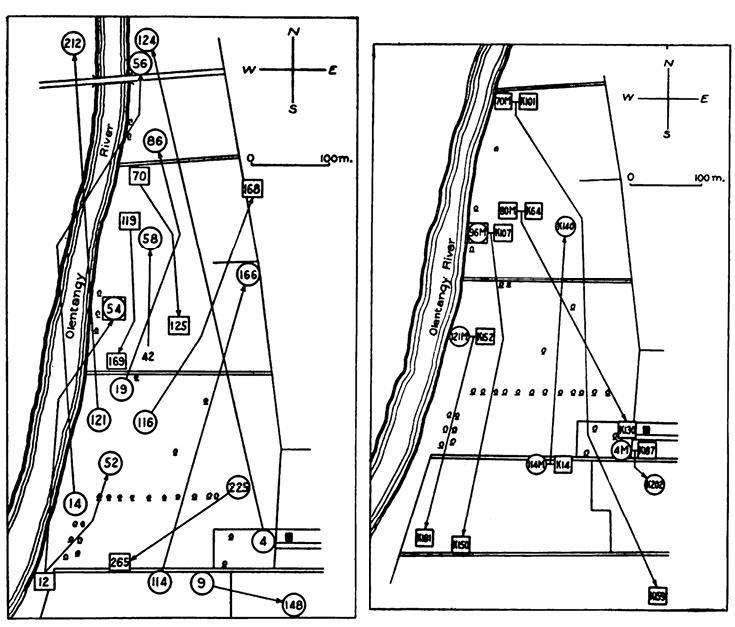

Figure 2. Maps from Nice (1937). Left: Territories of 13 Males in Relation to Birth Place. 9 residents, 4 summer residents. Right: Territories of 6 Females in Relation to Birth Place, 2 residents, 4 summer residents.

The second volume, which was more theoretical, concentrated on the behavior of the Song Sparrow, compared this behavior to that of other species, and included research that Nice had done on hand-reared birds. When the second volume was published in 1943 the reviews were, if possible, even more laudatory:

The second part of Mrs. Nice's ‘Studies in the Life History of the Song Sparrow' is a work of much wider interest and value than the first part, admirable as that one is. … No one else knows as much about the bird as she does. A large part of the material is new to ornithological literature … Seven years of intensive, meticulous and intelligent field and aviary studies have yielded a rich harvest of detailed, individualized, observational data both quantitatively and qualitatively incomparably in advance of what we have for any other bird species. Added to this we have in the present book a great number of interpretations and suggestive comments that are themselves a digest of a vast and not always readily assimilable literature. In other words, Mrs. Nice's book presents more information than we have ever had about any single species, more thoroughly analyzed, and more completely integrated with current knowledge and modern concepts of animal behavior. … Its author and the Linnaean Society are to be congratulated on the publication of the most searching study yet made of any wild bird. (Friedmann 1943)

A review by Ernst Mayr states:

This treatise is far superior to anything of the kind that has been previously attempted. Many of the chapters … are complete treatises in themselves with enough meat in them to fill separate volumes. (quoted in Burtt 2003)

For her Song Sparrow work, Nice received the Brewster Medal in 1942, the highest award given by the AOU. Margaret Morse Nice had become an internationally celebrated ornithologist.

Writing papers and reviews for Bird-Banding (now Journal of Field Ornithology)

In her life-history studies, Nice recognized how important it was to recognize individual birds in the field, and her individual banding technique provided her the tools to do so. Thus, she was drawn to Bird-Banding, the journal of the Northeastern Bird-Banding Association that began publication in 1930, and she published a number of her papers on life history research in that journal, many of which involved banding (e.g., Nice 1931c, 1933c, 1934a).

Nice, in her year in Europe in 1932, had become aware of how poorly most American ornithologists understood the European ornithological literature and resolved to do something about it. In her autobiography she states:

Gradually, from reading foreign journals and, in 1932, meeting so many foreign birds and ornithologists, I resolved to try my hand at educating Americans, as to what was being done in other countries in life history studies, and for foreigners as to what was being done in this country in the behavioural field. (Nice 1979)

She chose to do her educating by writing reviews of papers from foreign journals, which she published in Bird-Banding. Though most journals published reviews of books only, Nice, for her contributions to Bird-Banding, concentrated on succinctly reviewing individual papers. She contributed 18 reviews to the first issue in 1934 and then roughly 50 per issue for the next nine years, a total of approximately 1,800 reviews, until World War II disrupted communications. Subsequently, she continued writing reviews for Bird-Banding and her total number of reviews over a 35-year period was an astounding 3,280. In 1935, because of her reviews, she became an Associate Editor of Bird-Banding. She also became involved in editorial work for the Wilson Bulletin. In August, 1936, the Nice family moved to Chicago where her husband, Blaine, had taken a professorship at Chicago Medical School.

Awards and honors, and the research continues

In 1937, Nice began to reap the rewards of her successful research when she was elevated to Fellow in the AOU, the same year that Ernst Mayr was made a Fellow. She had joined the Wilson Ornithological Club (now Society) in 1921, and presented the first of many papers at the 1927 annual meeting, beginning a long and fruitful relationship with this society. She became the first woman President of the Wilson Ornithological Society 1937, and the first woman to be President of any major ornithological organization in the world. The following year, after attending the International Ornithological Congress in France, she spent a month doing research in Austria with Konrad Lorenz, a prominent European ethologist-ornithologist, who had been an inspiration to her. Nice had become friends with Lorenz when she attended the 1934 International Ornithological Congress in Oxford, England. She also became friends with Niko Tinbergen, another prominent ethologist. Ethology, the science of animal behavior, was being developed in Europe in the 1930s and Nice, along with Ernst Mayr, are given credit for introducing this field of study to the United States (Barrow 1998).

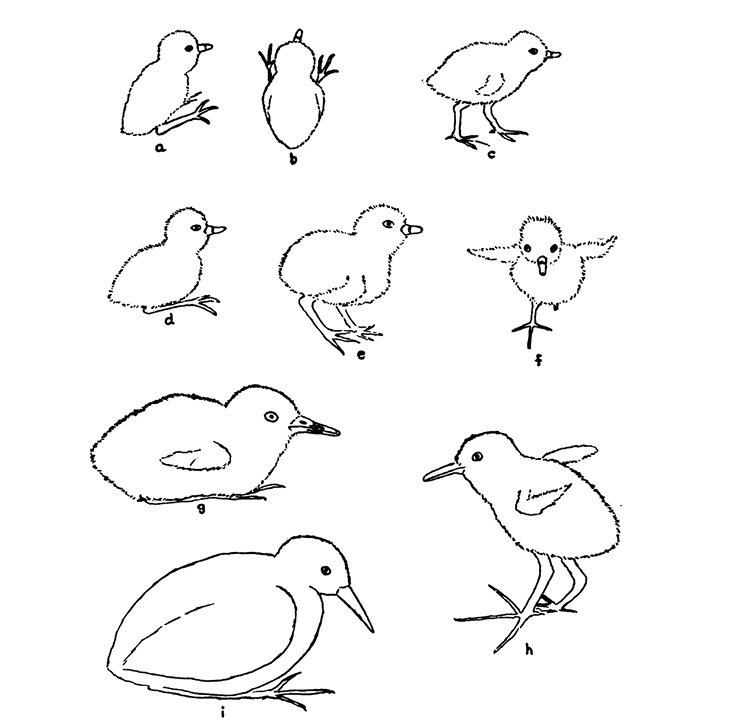

Margaret Morse Nice's sketches of the development of Virginia Rail from 1 to 31 days. Image from Nice (1962).

During the late 1930s and early 1940s Nice continued her Song Sparrow research, principally with captive birds. She had done research on captive birds in Oklahoma, including a study of a hand-raised Brown-headed Cowbird (Nice 1939a). In 1939, she published a book, The Watcher at the Nest, which was illustrated by Roger Tory Peterson and aimed at a broad audience of birdwatchers as well as ornithologists. It consisted of a popular treatment of her Song Sparrow research and life history work on other bird species. It concluded with a plea for conservation:

This world would be a far lovelier and more wonderful place to live in, if we left some space for the wild creatures, some forests for the beasts and birds, some swamps for the wild fowl, some prairie for the wild flowers. (Nice 1939b, p. 154).

Following her recovery from health problems during the 1940s, Nice spent four summers studying the development of precocial species, mostly ducklings, and this work was published as another book-length monograph by the Linnaean Society of New York (Nice, 1962). Following World War II, Nice was influential in the relief efforts to help European scientists, many of whom were German.

Nice was a soft-spoken person but could respond forcefully if irritated. In my interview with Ernst Mayr he presented an example:

Now let me say a little something about Mrs. Nice. … she always said … in conversation that there was nothing that annoyed her worse, that made her more angry, than when somebody referred to her as the housewife Margaret Morse Nice. She said, "that I was a housewife is completely immaterial. I was a professional ornithologist except I didn't have a paid position.

Nice didn't hesitate to express her opinions or outrage about issues of the time. She wrote letters to the editors of magazines, including Life, Time, and Reader's Digest, and to any newspaper whose editorials she found fault with. The subjects she responded to were varied and included responses to proposed changes in hunting regulations, supporting the use of live animals in medical research, imposing fines on the owners of cats that killed birds, and overpopulation by humans as a fundamental world problem. She even wrote President Harry Truman about the dangers of McCarthyism. Most of her letters involved conservation issues. For example, she wrote to the Secretary of the Interior urging him to tighten hunting regulations, prohibit permanently the use of bait or live decoys in hunting, and ban lead shot.

The awards and honors continue to pour in

Margaret Morse Nice received many awards and honors for her brilliant ornithological work. In 1955, she was awarded an honorary Doctor of Science degree by Mount Holyoke College, and she received a second doctorate from Elmira College in 1962. In 1998, the Wilson Ornithological Society established the Margaret Morse Nice Medal "in recognition of her scientific creativity and insight, her concern for education of young and amateur ornithologists, and her leadership as an innovator and mentor. The medal honors a lifetime of contributions to ornithology." (Burtt 1998) Recipients of the Medal are invited to give an opening plenary lecture at the Wilson Society's annual meeting.

Niko Tinbergen, one of the world's most prominent ecologists, wrote her a letter on her 75th birthday:

In a long life you have found rewards not only in the home circle for all your cares and sacrifices, but with remarkable creative power you have served science. Through your works you have become known to ornithologists throughout the entire world as the one who laid the foundation for the population studies now so zealously persecuted [sic]. (quoted in Trautman 1977, p. 438)

After her death in June, 1974, the accolades continued. The editor of Bird-Banding wrote "We are all saddened by the loss of this friend from the ornithological society, but what a productive and exemplary life she led!" (Editor [David W. Johnston] 1974). In the same Memoriam, Ernst Mayr is quoted: "I have always felt that she, almost single-handedly, initiated a new era in American ornithology … She early recognized the importance of a study of bird individuals because this is the only method to get reliable life history data."

Margaret Morse Nice led a long and fruitful life. Her childhood experiences and higher education in Massachusetts provided a strong foundation for her later research. Nice achieved international recognition both for her research and for bringing American and European ornithology closer together. Also, she was influential in opening ornithology to women, a field that was dominated by men in the early 1930s. The scope and quality of her research and achievements remain an inspiration.

Literature cited

- Barrow, M. V. Jr. 1998. A Passion for Birds: American Ornithology after Audubon. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Burtt, E. H. Jr. 1998. Wilson Ornithological Society establishes Margaret Morse Nice Medal. Wilson Bulletin 110: 25–27.

- Burtt, E. H. Jr. 2003. Margaret Morse Nice: "…a very important individual –". Bird Observer 31: 16–22.

- Delacour, J. 1937. Review of: Nice (Margaret M.), Studies in the Life History of the Song Sparrow, 1. (in French) L'Oiseau 7: 655–656.

- Editor [David W. Johnston]. 1974. Obituary, Margaret Morse Nice (1883-1974). Bird Banding 45: 360.

- Friedmann, H. 1943. Studies in the life history of the Song Sparrow, II. By Margaret Morse Nice [a review]. Wilson Bulletin 55: 250–252.

- Nice, M. M. 1910. Food of the Bobwhite. Journal of Economic Entomology 3: 295–313.

- Nice, M. M. 1922. A study of the nesting of Mourning Doves [Part 1]. Auk 39: 457–474.

- Nice, M. M. 1923. A study of the nesting of Mourning Doves [Part 2]. Auk 40: 37–58.

- Nice, M. M. 1925. Changes in bird life in Amherst, Massachusetts in twenty years. Auk 42: 594.

- Nice, M. M. 1926. Study of the nesting of the Magnolia Warbler. Wilson Bulletin 38: 185–199.

- Nice, M. M. 1929. Some observations on the nesting of a pair of Yellow-crowned Night Herons. Auk 46: 170–176.

- Nice, M. M. 1930a. A study of a nesting of Black-throated Blue Warblers. Auk 47: 338–345.

- Nice, M. M. 1930b. The technique of studying nesting Song Sparrows. Bird-Banding 1: 177–181.

- Nice, M. M. 1931a. A study of two nests of the Ovenbird. Auk 48: 215–228.

- Nice, M. M. 1931b. Survival and reproduction in a Song Sparrow population during one season. Wilson Bulletin 43: 91–102.

- Nice, M. M. 1931c. Returns of Song Sparrows in 1931. Bird-Banding 2: 89–98.

- Nice, M. M. 1931d. The Birds of Oklahoma, Revised Edition. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Nice, M. M. 1932a. Observations on the nesting of the Blue-gray Gnatcatcher. Condor 34: 18–22.

- Nice, M. M. 1932b. The Song Sparrow breeding season of 1931. Bird Banding 3: 145–150.

- Nice, M. M. 1933a. The theory of territorialism and its development. pp. 89–100 in Fifty Years' Progress of American Ornithology (1883-1933). Lancaster, Pennsylvania: American Ornithologists' Union.

- Nice, M. M. 1933b. Zur Naturgeschichte des Singammers [I]. Journal für Ornithologie 81: 552–595.

- Nice, M. M. 1933c. Nesting success during three seasons in a Song Sparrow population. Bird-Banding 4: 119–131.

- Nice, M. M. 1934a. The opportunity of bird-banding. Bird-Banding 5: 64–69.

- Nice, M. M. 1934b. Zur Naturgeschichte des Singammers [II]. Journal für Ornithologie 82: 89–100.

- Nice, M. M. 1937. Studies in the life history of the Song Sparrow. I. A population study of the Song Sparrow. Transactions of the Linnaean Society of New York 4: 1–247. (Reprinted by Dover, 1964).

- Nice, M. M. 1939a. Observations on the behavior of a young cowbird. Wilson Bulletin 51: 233–239.

- Nice, M. M. 1939b. The Watcher at the Nest. New York: Macmillan.

- Nice, M. M. 1943. Studies in the life history of the Song Sparrow. II. The Behavior of the Song Sparrow and Other Passerines. Transactions of the Linnaean Society of New York 6: 1–328. (Reprinted by Dover, 1964).

- Nice, M. M. 1962. Development of behavior in precocial birds. Transactions of the Linnaean Society of New York 8: 1–211.

- Nice, M. M. 1979. Research Is a Passion With Me. Toronto, Ontario: Consolidated Amethyst Communications, Inc.

- Nice, M. M., and L. B. Nice. 1924. The Birds of Oklahoma. University of Oklahoma Bulletin; University Study No. 286.

- Nicholson, E. M. 1937. Review of: ‘Population study of the Song Sparrow." By Margaret M. Nice. British Birds 31(8): 276–277.

- Ogilvie, M. B. 2018. For the Birds: American Ornithologist Margaret Morse Nice. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Trautman, M. B. 1977. In Memoriam: Margaret Morse Nice. Auk 94: 431–441.