Mark Lynch

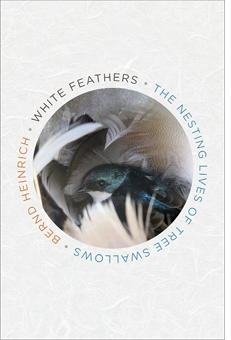

White Feathers: The Nesting Lives of Tree Swallows. Bernd Heinrich. 2020. Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

White Feathers: The Nesting Lives of Tree Swallows. Bernd Heinrich. 2020. Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

"One swallow makes not a spring, nor one woodcock a winter."

(p. 143, A Collection of English Proverbs by John Ray, 1678)

How much time do you spend looking at any single bird? You may spend more time if that bird is a rarity or a particularly colorful species. Maybe you will spend more time if you are trying to snag a perfect photograph. But on the average, I imagine you spend anywhere from a few seconds to a few minutes studying any one bird you come across in the field. Less time if it's a common species. That's because so much of birding involves moving along as quickly as possible to the next bird and the next and the next. We are always hoping to hit the jackpot and find something special. And as soon as we do, the search begins again.

Imagine looking at just one pair of birds for hours every day during the summer breeding season, for six consecutive summers. That is what Bernd Heinrich did with a pair of Tree Swallows. Bernd Heinrich is an internationally acclaimed scientist, avid runner, and author of many books, including several that are considered classics of natural history. His approach to science and looking at the natural world can only be described as "old school" in the best possible sense. He will come across some odd bit of behavior of a bird or even an insect and begin to ask a series of basic questions. This impels him to then carefully observe that species over long periods of time, sometimes years, until he has wrestled answers from these observations. Often, he will come up with a series of experiments that he will execute in the field and very carefully observe the results, taking copious notes, timing everything. Typically, even more questions will arise in the process. Some questions will go unanswered, at least for now. Nowadays, this whole personal process of scientific investigation will occur at Heinrich's cabin, deep in the Maine woods. It's not that Heinrich is some kind of ornithological Luddite. Far from it. He has a deep knowledge and appreciation of contemporary scientific research and techniques. He is always searching the literature to help him find answers. But Heinrich is convinced that careful and prolonged observations in the field have as much worth as careful experiments in a laboratory or another controlled environment.

In 2010, while living in Vermont, Heinrich opened a Tree Swallow box and noticed something odd. Besides the typical nesting materials of grasses, there were a number of pure white feathers laid on top. This observation begins a series of questions. Do all Tree Swallows do this? Where do these white feathers come from? At what point in the nesting process do the swallows bring in the white feathers? Is it the male or female or both that place the feathers in the nest.

Most of us making an observation like this would probably assume that there would be an answer in the literature. After all, nesting Tree Swallows have been extensively studied, typically in carefully controlled grids of many nest boxes. But Heinrich searches the published literature and finds no answer to his questions about the white feathers. In 2011, Heinrich moves to a remote cabin in the Maine woods that has a half-hectare clearing just outside his door. There is no one, not even a farmer, for miles. He puts up several Tree Swallow boxes in this clearing and is gratified that a pair takes up residence. Heinrich recalls his observation of the white feathers and is off on another adventure.

You may think of Tree Swallows as a very common species and can't imagine watching a pair closely for a prolonged period. But Heinrich has always thought of Tree Swallows as a perfect subject for a study. "There is arguably no bird in the world that combines graceful flight, beauty of feathers, pleasing song, and accessibility, plus tameness and abundance, more than the tree swallow (Tachycineta bicolor)." (p. xi)

If you have a Tree Swallow box on your property, you may think you have observed this species carefully. What Heinrich has in mind is something much more focused and intense. "Ordinarily we barely glance at swallows; I wanted to watch them deliberately and get to know them intimately." (p. xiii) This entails Heinrich getting up well before dawn with a fresh cup of coffee in hand and beginning to watch even before the swallows arrive. Heinrich wants details of swallows' behavior even before they begin nesting.

"Tree swallows usually return more than a month before they begin to nest, when snow may still be in the woods and few flying insects are available for food." (p. 25) Once they do arrive, he plops himself down in a chair close to the nest box and carefully takes notes, and even times every part of their nesting behavior. There are detailed descriptions of the various swallow vocalizations. He describes carefully how the swallows bring nesting material to the boxes and how many trips they make in doing so. There are many interesting interactions between the male and the female, and Heinrich watches where they perch and what they eat. He continues this painstaking process through the entire nesting period until all the young swallows have, with luck, fledged and left the nest. The next summer, he begins again.

For the first couple of years, it appears to be the same pair of Tree Swallows that come to nest. Heinrich knows this from their behavior on arrival.

A further sign of their being back home: within seconds of landing one of the pair swooped down from that high perch to land directly in the entrance of the same nest-box (there were eight others available) used last year. It was next to the garden, on a pole two meters from the ground. The second bird followed, and both entered the nest-box without hesitation." (p. 26)

He first acclimates the pair to his presence, so that he can approach them closely and even open the box to look at the nestlings. He then begins a series of experiments to investigate how they use the white feathers.

I had saved white feathers for the pair. I began offering after the nest looked finished, and they took each one almost off my fingers when I tossed it into the air. I offered a dark feather, which had white markings, while the pair was perched side by side fifty meters from me on "their" locust tree. As I stepped out the cabin door and tossed this feather into the air, the reaction took me by surprise—the female instantly dived off her perch, caught it in midair, flew up past her mate, and carried the feather into the nest, which at that point had no feathers in it. Previously I had thought that it was the male who got the feathers. Wrong again. (p. 28)

I will not reveal his findings because that would be a spoiler. But as he continues his observations over the years, not always with the same pair, Heinrich begins to notice other more complicated aspects of Tree Swallow behavior. He observes several instances of "egg dumping" in which an interloping female lays her eggs in the nest of another pair. This is a breeding strategy fraught with problems. "When a female succeeds in foisting parental care on unsuspecting victims, the cost to the nest can be high. There will be too many babies, and some will die." (p. 39) Too many eggs laid in a nest means too many young need to be fed, and ultimately that one or more young will not survive to fledging. There is an optimal number of young in every nesting, typically three and sometimes four. Three young mean the parents will be able to clean the nest easily and bring enough food to allow all the nestlings to grow properly. One extra egg dumped in a nest from a brood parasite can have disastrous results for all the swallows. The timing of this egg-dumping is critical.

Timing is extremely critical: an egg that is inserted a day or two late will become the runt of the litter (except among birds with precocial young, which are born with the ability to feed themselves from the start), prone to starve in the competition for food among the young. Conversely, an egg inserted before the host has laid one of her own could potentially be discriminated against, so long as the host knows whether she has laid an egg. After she has laid an egg and a foreign one is inserted, the chances are even that any egg she removes or destroys will be her own. Thus, for the egg cuckold to be successful, the female should insert the parasite sometime during the time of egg laying, and assess the nest contents to time it right." (p. 39-40)

As the years pass, Heinrich realizes that he is becoming familiar with the behaviors of Tree Swallows on a level not achieved by conducting more carefully controlled experiments.

"My" tree swallows were beginning to reveal their struggles in a way that felt far richer and more exciting than the studies of tree swallows that I was reading. Researchers had studied swallows living in identical boxes set up in huge symmetrical grids in order to get consistent and statistically significant results. I was now eager to see the swallows the next spring, to observe how individuals might deal with the more natural situations of this clearing in the woods." (p. 47)

This kind of personal study of the Tree Swallows means that Heinrich can suddenly change his protocols when he makes a fortunate find. Like taking advantage of a roadkill.

I might have left it at that, but for my discovery of a black-and-white domestic road-killed duck. Its feathers offered a perfect control for testing the swallows' color preference. They were all duck feathers, but what variety—black or white in color, short or long in shape, fluffy or smooth in texture. I plucked and stored enough feathers for tests of several swallows in several seasons. (p. 65)

He sets out white feathers on black paper, black feathers on white paper, and offers the swallows feathers that are part black and white. Which do the swallows prefer? You will need to read the book to find out.

Nothing escapes Heinrich's close observations. Peeking into the nest box, he notices that one of the young has a bit of an insect sticking out of its mouth. Nothing escapes Heinrich's observations, so of course he has to try to identify what insect this is from the small fragments left. "I found a mayfly jutting out of the side of one nestling's mouth. Only one leg of its normal six remained, and its three long tail bristles were missing, but enough was left for me to tentatively identify it as Ephemera simulans, the brown drake. Well known as bait for trout fishing." (p. 80)

Heinrich's observations of the tense fledging process are some of the best sections in this book. It's a tense process, with the parents trying to lure the young out of the box with calls and food. Typically, most make their first tenuous flights to a nearby bush and eventually follow the adults to a staging area before migration. Often one bird is left behind, too weak from not being fed properly because there were too many young in the nest. Time is short, and the swallows need to move on. The parents may make a few attempts to get the weakened young one up and moving, but typically the adults leave and the young perish.

By observing a single nesting pair of birds closely over such a long time, chances are you will observe something really out of the ordinary. One of the strangest occurrences in White Feathers is Heinrich's discovery of a nest box full of bloody, macerated, dead nestlings when just the day before they were all fine. Also found in the nest box was a live Nicrophorus pustulatus. This is a species of burying or sexton beetle. Heinrich has written extensively before about burying beetles around his cabin, but he had never seen this species before! Typically sexton beetles bury small carcasses of mice and shrews and lay their eggs on the corpse. The larvae then feed on the decaying body. Heinrich explains, "But N. pustulatus has the singular habit of burying turtle eggs instead, using them, rather than animal carcasses, as food for its larvae. Finding this beetle, in this context, was beyond bizarre." The nearest pond is some distance away. How did this very odd beetle end up in a Tree Swallow box? Was it responsible for the death of all the fledglings? You will have to read White Feathers to find out.

In a final chapter, Heinrich follows the swallows out of his yard, and on into fall migration, and over-wintering much farther south. The reader is no longer sitting beside Heinrich in his yard, but following the swallows' long journey south..

From this day on, as in other years, the tree swallows disappeared as if swept from the country. In my mind I would follow their journey to winter roosts in the swamps and wetlands along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts, to gatherings of millions that funnel out of the evening sky, a mass of swallows like smoke descending to enter the reed thickets where they rest overnight. Tree swallows are birds of the sky. I will miss them, and I wish them a good journey, with plenty of bayberries to eat on the Maine coast, lots of bugs in the South, and as always, safe travels back home. (p. 207)

White Feathers is not like most birding literature and also unlike any ornithological paper you have read. The pace of the book is the pace of the breeding season of the one pair of Tree Swallows. The rhythms of the book are the rhythms of the natural world. It is filled with what at first may seem to be small observations. Over the pages of White Feathers these observations aggregate to give the reader a very intimate peek at the life of a wild bird family. White Feathers includes a small section of color photographs and a number of Heinrich's black-and-white drawings. There is also a section that lists some of the most important published papers on the Tree Swallow.

As I write this review, we are still in the midst of the ravages of the Covid-19 virus, and many of us are staying home, yearning to be out birding without restrictions. White Feathers is a perfect book to read while you are marooned at home, showing us that careful observation of the common life found just outside our door can be fascinating and important.

White Feathers is not just about Tree Swallows. As we watch the swallows nest, we also get to know that particular cabin in the woods, the other life around it, and Heinrich himself, who is always good company. A close reading of White Feathers will encourage the reader to stop and linger over your next Tree Swallow sighting and encourage all of us to pose more questions about what we are looking at in the natural world.

"For one swallow does not make a summer, nor does one day; and so too one day, or a short time, does not make a man blessed and happy." (Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics)