Jonathan L. Atwood

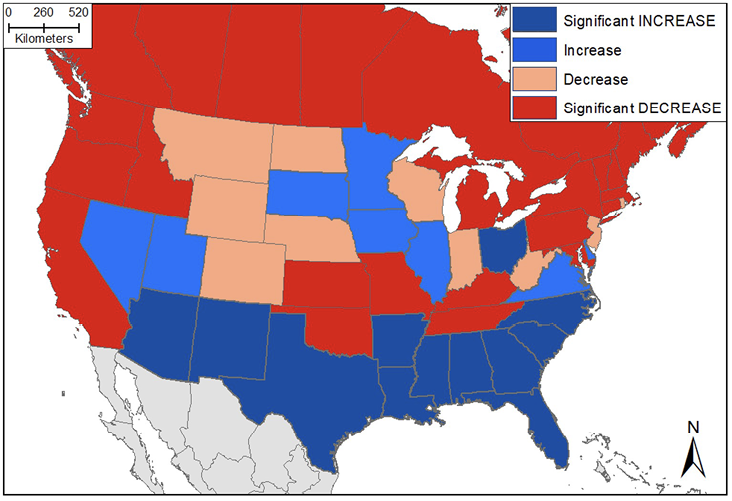

Figure 1. North American population trends of Barn Swallow, by state and province, based on USGS Breeding Bird Survey data, 1966–2017 <https://www.mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov/>, scale = states; Sauer et al. 2017).

Anticipating field research on important conservation topics may seem far removed from the many challenges of the Covid-19 pandemic. Yet Mass Audubon’s conservation science department is planning a couple of specific projects that may be of particular interest to Bird Observer readers. These projects—on Barn Swallows and American Kestrels—will begin in April 2021, and we hope to have results that can be reported here sometime in the fall or winter.

Barn Swallows

Barn Swallows (Hirundo rustica) belong to a suite of aerial insectivores that are undergoing serious population declines in northeastern North America. Although a common, widespread species that occurs throughout most of the world, U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Breeding Bird Survey data (Sauer et al. 2017) indicate that, over a 45-year period (1970–2014), the overall population of this species in the United States and Canada has decreased by an estimated 38% (Rosenberg et al. 2016). The Canadian population has declined approximately 80% since 1970, leading the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) to assess the Barn Swallow as Threatened (COSEWIC 2011).

Population trends within the Barn Swallow’s North American range vary geographically (Figure 1). Numbers are increasing in the southern tier of states from Arizona east to North Carolina. All of the Canadian provinces, California, and northwestern, midwestern, northeastern, and mid-Atlantic states generally show declining populations—with trends that are less pronounced in the Midwest. In Massachusetts, based on 29 Breeding Bird Survey routes, there has been an estimated 1.1% annual decline in abundance of Barn Swallow from 1966–2017 (Sauer et al. 2017). These declines were not reflected by Massachusetts Breeding Bird Atlas data, which showed a stable or increasing state-wide breeding distribution between the two atlas periods (1974–1979 and 2007–2011), although Walsh and Petersen (2013) nonetheless commented that the species merited “further monitoring and conservation action.”

The causes of Barn Swallow declines are unclear. BirdLife International stated that at a global scale,

The main threat to the species is the intensification of agriculture. Changes in farming practices such as the abandonment of traditional milk and beef production have resulted in a loss of suitable foraging areas. In addition, intensive livestock rearing, improved hygiene, land drainage and the use of herbicides and pesticides all reduce the numbers of insect prey available. Suitable nest sites for Barn Swallows are often scarcer on modern farms. The species is susceptible to changes in climate with bad weather in the wintering areas as well as the breeding grounds affecting breeding success (Tucker and Heath 1994). It is occasionally hunted for sport and nests are sometimes removed as a nuisance. In North America, introduced House Sparrows (Passer domesticus) are serious nest-site competitors, taking over nests and destroying eggs and nestlings (Turner and Christie 2012). (BirdLife International 2016)

In Canada, where the species is listed as Threatened, COSEWIC (2011) concluded that “the main causes [of decline] . . . are thought to be: 1) loss of nesting and foraging habitats due to conversion from conventional to modern farming techniques; 2) large-scale declines (or other perturbations) in insect populations; and 3) direct and indirect mortality due to an increase in climate perturbations on the breeding grounds (cold snaps).” Møller (2001) noted that the number of swallows in Denmark declined when dairy farming was shifted to crop production. Nebel et al. (2010) concluded that “the taxonomic breadth of these downward trends [among 24 species of aerial insectivores, including Barn Swallows] suggests that population declines are linked to changes in populations of flying insects, and these changes might be indicative of underlying ecosystem changes.”

Barn Swallows typically feed at lower heights—often less than one meter above the ground and usually no more than 10 meters high—than most other North American swallows (Brown and Brown 2019). Brown and Brown (2019) suggested that “foraging low to the ground may enable the Barn Swallow to find more food and thus survive late-spring cold snaps better than species that forage at higher [altitudes] (e.g., Cliff Swallow, Purple Martin, Chimney Swift).” In New England, foraging birds are concentrated over grassy pastures, plowed fields, and around farmyards and domestic animals. Brown and Brown (2019) observed that Barn Swallows “often feed on insects flushed by farm implements, domestic or wild grazing mammals, humans, and flocks of other bird species.” There is no evidence of coordinated group foraging (Snapp 1976), although Hebblethwaite and Shields (1990) found that birds may occasionally cue on the foraging activities of conspecifics.

Little is known about the foraging habitat preferences of nesting Barn Swallows. Within the immediate vicinity of the approximately 40-pair breeding colony of Barn Swallows located on the Fort River Division of the Silvio O. Conte National Fish and Wildlife Refuge in Hadley, Massachusetts, are numerous agricultural fields that vary not only in ownership but also in management and landscape characteristics. Mass Audubon conducted preliminary surveys of Barn Swallow nesting sites within 10 kilometers of Hadley during 2020. Of 1,324 grid cells, each 50 hectares in size, that were visited, 145 (11%) contained barns or other structures that appeared potentially suitable for nesting Barn Swallows. Of these potential sites, Barn Swallows were found at 38 (29%).

In the coming study we will place lightweight—approximately 0.32-gram—nanotags on 20 adult Barn Swallows captured at the Fort River Division nesting site. We will use mist-netting capture methods that during 2019 and 2020 allowed us to capture and band 160 individuals. Systematic surveys of agricultural landscapes located within 10 kilometers of the Fort River nest site will then be carried out using a handheld telemetry receiver to detect marked individuals at potential foraging sites. An important part of this study will be to describe the characteristics—crop type, harvest activities, presence of livestock, proximity of water, presence of other aerial insectivores—of fields being used by foraging swallows, as well as descriptions of fields where swallows were not observed or detected.

We also hope to establish insect sampling stations in selected agricultural fields representing the range of management approaches in the landscape surrounding the Fort River breeding colony. This sampling will help us measure insect abundance at the various fields and relate that information to swallow foraging behavior and agricultural management approaches.

Our work on Barn Swallows in the Hadley area will be made possible by financial support from the Blake-Nuttall Fund of the Nuttall Ornithological Club, the Silvio O. Conte National Fish and Wildlife Refuge, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Division of Migratory Birds.

American Kestrels

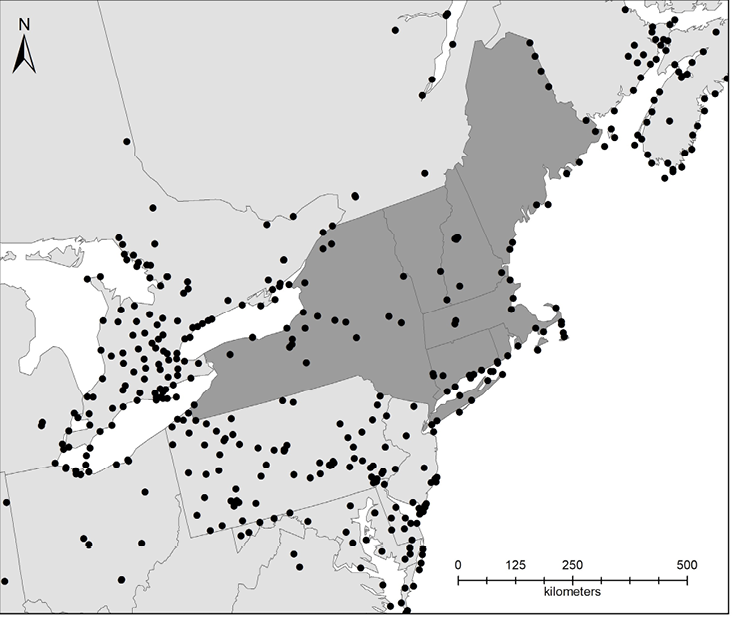

American Kestrels (Falco sparverius), a similarly iconic species of New England’s agricultural landscape, will also be a focus of Mass Audubon field research during the 2021 field season. Our work will be conducted as part of the Northeast Motus Collaborative’s <https://www.northeastmotus.com/> first field season. This project, which revolves around a multistate expansion of automated telemetry receiver stations in inland areas of the Northeast (Figure 2), will make use of the Motus Wildlife Tracking Network, spearheaded by Birds Canada <https://motus.org/>. Mass Audubon, in collaboration with the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, will capture and mark adult kestrels nesting in Massachusetts and assess movements of these birds as they migrate to and from southern wintering grounds.

Figure 2. Locations of active Motus receiving stations in northeastern North America as of January 26, 2021, based on data from https://motus.org/. Dark-shaded states are participants in the Northeast Motus Collaborative, which will add 50 additional stations in inland areas during 2021–2022.

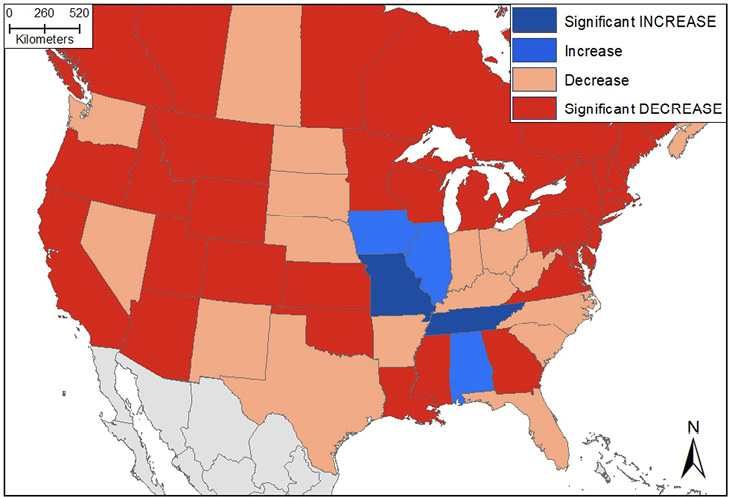

The American Kestrel, the smallest and most widely distributed falcon in North America, breeds in a variety of open and semiopen habitats throughout much of the United States. However, despite its broad range and apparent habitat availability, kestrels have undergone a widespread population decline, with some of the steepest declines occurring in the Northeast (Figure 3). As a result, the kestrel is included as a Species of Greatest Conservation Concern in the wildlife action plans of all six New England states. According to the Breeding Bird Survey, kestrels experienced a 5.3% annual decline in the New England and mid-Atlantic Coast region and an alarming 7.1% annual decline in Massachusetts during 1966–2015 (Sauer et al. 2017). Further confirmation of this precipitous decline comes from Mass Audubon’s Breeding Bird Atlases. The second Atlas (2007–2011; Walsh and Petersen 2013), documented kestrels in 289 fewer blocks than the first Atlas (1974–1979; Petersen and Meservey 2003). This decline was the second largest of all native breeding birds in Massachusetts.

Figure 3. North American population trends of American Kestrel, by state and province, based on USGS Breeding Bird Survey data, 1966–2017 (https://www.mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov/, scale = states; Sauer et al. 2017).

The specific causes of American Kestrel declines are not well understood. For kestrels in the Northeast, ornithologists generally believe that several factors are likely contributing to declines, with breeding habitat loss and nonbreeding period survival as possible leading factors. Kestrels prefer to nest in open areas over 50 acres in size (Smallwood and Bird 2002), including grasslands and agricultural fields, but such open areas have become increasingly uncommon in Massachusetts and New England. However, there remain numerous locations with seemingly suitable breeding habitat that lack nesting kestrels. This observation suggests that problems apart from the breeding grounds, such as elevated mortality rates during the migratory and over-wintering periods, also may be important factors. In collaboration with the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, Mass Audubon hopes that the data collected as kestrels migrate past the Motus telemetry array will help us better understand threats to kestrels across their life cycle, thereby enabling more effective maintenance and protection of suitable habitat.

Our work on American Kestrels in Massachusetts will be funded by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Competitive State Wildlife Grant CFDA 15.634.

References

- BirdLife International. 2019. Hirundo rustica. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e.T22712252A137668645. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T22712252A137668645.en. Accessed February 25, 2021.

- Brown, M. B. and C. R. Brown. 2019. Barn Swallow (Hirundo rustica), version 2.0. In Birds of North America (P. G. Rodewald, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bna.barswa.02. Accessed October 23, 2019.

- COSEWIC. 2011. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica in Canada. Ottawa: Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/species-risk-public-registry/cosewic-assessments-status-reports/barn-swallow-2011.html

- Hebblethwaite, M. L. and W. M. Shields. 1990. Social influences on Barn Swallow foraging in the Adirondacks: a test of competing hypotheses. Animal Behaviour 39 (1):97–104.

- Petersen, W. R. and W. R. Meservey. 2003. The Massachusetts Breeding Bird Atlas, 1974–1979. Lincoln, Massachusetts: Massachusetts Audubon Society.

- Møller, A. P. 2001. The effect of dairy farming on Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica abundance, distribution and reproduction. Journal of Applied Ecology 38 (2):379–390.

- Nebel, S., A. Mills, J. D. McCracken, and P. D. Taylor. 2010. Declines of aerial insectivores in North America follow a geographic gradient. Avian Conservation and Ecology-Écologie et conservation des oiseaux 5 (2):1. http://www.ace-eco.org/vol5/iss2/art1/. Accessed October 23, 2019.

- Rosenberg, K. V., J. A. Kennedy, R. Dettmers, R. P. Ford, D. Reynolds, J. D. Alexander, C. J. Beardmore, P. J. Blancher, R. E. Bogart, G. S. Butcher, A. F. Camfield, A. Couturier, D. W. Demarest, W. E. Easton, J. J. Giocomo, R. H. Keller, A. E. Mini, A. O. Panjabi, D. N. Pashley, T. D. Rich, J. M. Ruth, H. Stabins, J. Stanton, and T. Will. 2016. Partners in Flight Landbird Conservation Plan: 2016 Revision for Canada and Continental United States. Partners in Flight Science Committee. https://partnersinflight.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/pif-continental-plan-final-spread-single.pdf

- Sauer, J. R., D. K. Niven, J. E. Hines, D. J. Ziolkowski, Jr, K. L. Pardieck, J. E. Fallon, and W. A. Link. 2017. The North American Breeding Bird Survey, Results and Analysis 1966–2015. Version 2.07.2017, Barn Swallow. Laurel, Maryland: U.S. Geological Survey Patuxent Wildlife Research Center. https://www.mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov/cgi-bin/atlasa15.pl?06130&1&15&csrfmiddlewaretoken=3YKakk7LxT2ki6NSpl4mstudYCqdW02C. Accessed October 23, 2019.

- Smallwood, J. A. and D. M. Bird. 2020. American Kestrel (Falco sparverius), version 1.0. In Birds of the World. (A. F. Poole and F. B. Gill, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.amekes.01 Accessed February 7, 2021.

- Snapp, B. D. 1976. Colonial breeding in the Barn Swallow (Hirundo rustica) and its adaptive significance. Condor 78:471–480.

- Tucker, G. M. and M. F. Heath 1994. Birds in Europe: their conservation status. Cambridge, U.K.: BirdLife International.

- Turner, A. and D.A. Christie, 2012. Barn Swallow (Hirundo rustica). In Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive (J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, J. Sargatal, D.A. Christie and E. de Juana, Eds.). Barcelona, Spain: Lynx Edicions.

- Walsh, J. M. and W. R. Petersen. 2013. Massachusetts Breeding Bird Atlas 2 (2007–2011). Lincoln, Massachusetts: Massachusetts Audubon (published by Scott and Nix).

Jon Atwood is Director of Bird Conservation for Mass Audubon. After completing his master’s and doctoral degrees in southern California, he moved to the East Coast in 1986. While working at Manomet Bird Observatory (now Manomet, Inc.) during the early 1990s, he collaborated in the analysis of the first 30 years of Manomet’s landbird banding effort, spearheaded federal protection of the California Gnatcatcher under the U.S. Endangered Species Act, led a long-term study of factors affecting Least Tern colony site selection, and contributed to early studies of Bicknell’s Thrush in New England. From 1998 to 2011, he directed the Conservation Biology Program at Antioch University New England and mentored over 70 graduate students working on various wildlife studies.