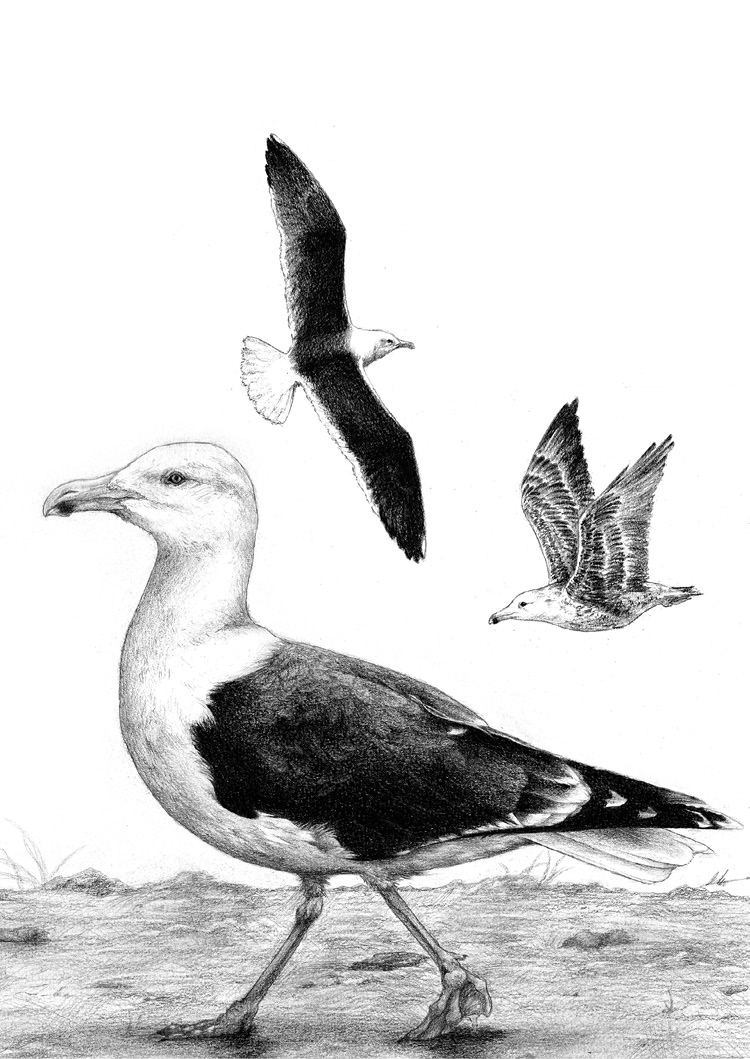

Great Black-backed Gull by Avery Whitlock

Avery Whitlock is a freelance illustrator based in Massachusetts. She is a Brookline Bird Club featured artist, a volunteer bird banding assistant, and a parent to two boisterous finches. Avery is largely inspired by the illustrations of Louis Agassiz Fuertes, and aims to depict birds with realism and an essence of their character.

To see more of Avery’s illustrations, go to <www.averywhitlockart.com/birds>

Great Black-backed Gull

The Great Black-backed Gull (Larus marinus) is the world’s largest gull species and the most aggressive gull in North America. Adults are a striking contrast of black and white. Their heads, bodies, and tails are white, their backs are black, and their black, white-tipped wings have a ribbon of white along the trailing edge. The legs are pale pink. The heavy bill is yellow with a red spot on the lower mandible. The sexes are similar in plumage, and males are slightly larger than females. First-year birds have whitish heads, black bills, and barred or checkered backs, wings, and bodies. They have a black terminal band on the end of their white tails. Second-year birds are mottled but lighter in color. Third-year birds begin to morph into adult plumage, which is attained in the fourth year. Great Black-backed Gulls can be confused with Western Gulls, but the latter are slightly smaller, have brighter pink legs, and their ranges do not overlap. Yellow-footed and Lesser Black-backed gulls have yellow legs, and the latter are smaller overall with longer and slimmer wings. Great Black-backed Gulls are monotypic, having no subspecies. They are closely related to the Kelp Gull of the Southern Hemisphere.

Great Black-backed Gulls breed along the coast and offshore islands from Labrador, Newfoundland, and Nova Scotia south along the East Coast of the United States to North Carolina. They also breed inland along the St. Lawrence River to the Great Lakes. They winter from Newfoundland south along the coast to central Florida and inland throughout the Great Lakes area. In Massachusetts, Great Black-backed Gulls are considered a locally abundant breeder along the coast and islands and are locally common in winter on the coast and inland. Spring migrants are active in March and April, and the fall migration and dispersal occur in September and October.

Great Black-backed Gulls are monogamous; pairs remain together for multiple seasons and, in some cases, for life. They breed for the first time in their fourth or fifth year and have a single brood per season. They are aggressively territorial; the male selects the territory and both male and female defend it. The calls of Great Black-backed Gulls are similar to those of other large gulls but lower in pitch. The “long call,” a series of repeated notes that is variable and elaborate, serves as a greeting call between mated birds. It also plays a role in courtship, with males giving the call with neck stretching and head tossing. Males may give a flight display with slower-than-usual wing beats and may also regurgitate food for females. There are several other calls that are associated with courtship or alarm and a variety of displays that are associated with territoriality and nesting. Fighting is common in defense of territory. For example, bill jabbing is common, or a gull will use its bill to grab an opponent’s tail, wing or neck. Grass pulling is also common in territorial disputes, as are half-running, half-flying charges at opponents. An aggressive upright display involves stretching the neck upwards with head pointed downwards. A crouching posture may sometimes include bill jabbing at a neighbor.

Pair formation begins in March or April. Nesting occurs in April or early May mostly on offshore islands on sand dunes, grassy areas, rocky outcrops, or in salt marshes. Great Black-backed Gulls nest in loose colonies, often with Herring Gulls or terns, but they may also nest solitarily. Early arrival—compared to other gulls and terns—insures access to the best nesting territories. Nests are scrapes that are filled with vegetation, feathers, and sometimes pieces of plastic or other refuse. The pair may make several scrapes but choose one for the final nest. The nest is often placed next to a rock or shrub that may offer some protection from the wind. The usual clutch is three greenish or buff eggs spotted or blotched with brown. Both parents develop incubation patches and both incubate the eggs. The incubation period is about a month. The chicks are semiprecocial; their eyes are open, they are covered in down, and they leave the nest in one or two days. Both parents feed the chicks by regurgitation. The chicks fledge after another month and may continue to be attended by the parents for up to six months.

Great Black-backed Gulls are generalist predators on a wide variety of marine fish, marine invertebrates, squid, insects, and the eggs, chicks, and adults of other gulls and marine birds, including terns, storm-petrels, and puffins. They are also scavengers on carrion and human refuse. Their foraging behavior is highly varied, from following the outgoing tide in pursuit of worms and crustaceans to pelagic diving one to two meters in depth, to floating on the surface and dipping into shallow water. They swallow small prey items whole but tear larger prey into pieces they can swallow. They often follow fishing vessels and join foraging flocks with other species such as shearwaters, other gull species, and cormorants. They have salt glands that remove the salt from seawater, but frequently search out fresh water for drinking.

Atlantic coast populations of Great Black-backed Gulls were severely depleted in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries by egg and plume hunters, and they were not recorded breeding in the United States again until the 1920s. They have since recovered to the point that, particularly on islands, control measures that include poisoning, nest destruction, and shooting adults have been instituted by state agencies and individuals to protect breeding habitat for other species such as terns from this large and aggressive gull. Adults have few natural predators, although eggs and chicks are taken by other gulls, Bald Eagles, Common Ravens, and the usual mammalian predators such as rats, raccoons, and coyotes. Great Black-backed Gulls mob predators and may even attack and strike humans. The world population is reportedly declining slightly, but the survival of Great Black-backed Gulls appears assured.

William E. Davis, Jr.