Skyler Kardell

The Gray Heron, originally found on September 5 on Tuckernuck, was subsequently refound the next day by a small party of observers on nearby Muskeget. All photographs by the author.

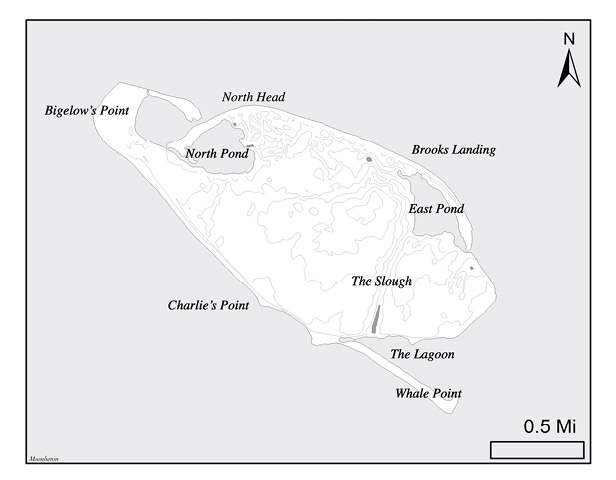

Tuckernuck is a privately-owned, low-lying island just a stone’s throw away from the “faraway” land of Nantucket, 28 miles southeast of mainland Massachusetts. A few kilometers north of Tuckernuck lies Muskeget Island, a remote slump of sand with a well-documented breeding history of gulls, terns, skimmers, and ducks written and catalogued by Wetherbee, Forbush, Mackay, and Snow, among others. Renowned naturalist Skip Lazell called Tuckernuck “surely the most remarkable bit of land along our entire Atlantic coast.” (Lazell 1976, p. 36) Various organizations, including the Nature Conservancy and the town of Nantucket, have assumed responsibility for the endangered Roseate Terns that nest there, and actively work to combat the ongoing threats that other avian inhabitants and visiting humans pose toward these birds. Farther still, across the Muskeget Channel, the island of Chappaquiddick can be seen on clear days from Bigelow’s Point or North Head on Tuckernuck, and often Cape Poge Lighthouse is visible as well. Nantucket Sound protects this broken archipelago from mammalian predators such as raccoon and otter as well as more sedentary raptors like Barred and Screech owls, all of which are unreported or absent here.

Map of Tuckernuck.

With just 38 residences, Tuckernuck exists without paved roads, an electric grid, or commercial enterprise—and no year-round population. From rare sandplain grasslands to young and stunted maritime oak forests, Tuckernuck hosts at least 14 unique habitat types with their own specialized communities of vegetation (Brace 2012). Both salt- and freshwater bodies occur on the island. Along the northwest side, minuscule kettle ponds host a sustainable population of snapping and spotted turtles, as well as a diurnal roost for both night-heron species. Where one might find an abundance of pinkletinks—as spring peepers are locally known—on nearby Nantucket, the meadows here are notably quiet; not a single frog can be found on Tuckernuck. Just west of the island’s only active runway, a brackish and phragmite-filled outwash pond affectionately known as “the slough” practically slices the island in two. Lazell (1976, p. 35) again sings the praises of this local wonder by claiming it is “one of the prettiest little fossil rivers I know of.” Herring and Great Black-backed gulls nest by the dozens along this morainal divide.

Whale Point stretches out from the southeast side of the island, connected by a tombolo. This is where the majority of the island’s Piping Plover nest, as well as a Least Tern colony of moderate size. Although this site has not historically been the best location for shorebirding during the months of August and September, good numbers of Calidris sandpipers gathered this year at a putrid and stagnant pond formed by heavy accretion along the south side of the point, instead of at their usual haunts of North Head and East Pond. Bigelow’s Point on the island’s west end continues to change dramatically, with erosion here occurring at a rate of upwards of 15 feet per year in some spots. This year, its shape took on a particularly stunted form, although this site was still able to host more than a dozen pairs of Great Black-backed Gulls above the cliff face, and at least two pairs of Piping Plover below it. Bigelow’s Point reliably provides the best sea watching on the island, especially following southeast blows when pelagic birds sustained on scraps from squid trawlers offshore are prompted closer to land. Staging terns will loaf at both Whale and Bigelow’s points in the thousands on their southbound migration.

A Hooded Warbler that appeared on August 19 proved to be the first of several birds seen over the course of the fall season on Tuckernuck.

North Head overlooks much of the sound and has breathtaking views of surrounding islands. This is the knobby part of Tuckernuck’s northwest side, an area owned predominantly by two island families. The main flow of westbound passerine migrants in morning flight almost exclusively departs from this landmass, as proved by my experience performing fall migration morning flight counts at both Bigelow’s Point and North Head. Some birds, such as Setophaga warblers and Red-eyed Vireo, will take off from this point at a high altitude and can be observed clearly flying out toward Muskeget, presumably with very little return flight. Other migrants, such as Pine Siskin—which began descending in mid-September in 2020—as well as nuthatches, woodpeckers, flycatchers, and orioles, will typically fly much lower. However, none of my encounters with true morning flight occurring on Tuckernuck has been able to rival the eye-level streams of migrants that may occur at other areas, such as Plum Island or Gooseberry Neck, where passerine fall migration can be observed. The exodus flights from Tuckernuck, less dramatic in numbers, are less clearly observable because of this difference in altitude, and flock composition can be much more difficult to discern.

My stay on Tuckernuck lasted from mid-May to mid-October of 2020, when I was employed as a coastal steward by the Tuckernuck Land Trust. I returned to Nantucket about once every two to three weeks to retrieve food and wash laundry items, but ultimately, I was on the island for the majority of my allotted time. In this way, I was able to observe the island’s biodiversity and changing avifauna throughout the seasons and during extreme weather phenomena. Hurricane Isaias brought Sooty Terns to Tuckernuck, as it did to much of the coastal and inland reservoirs from New York to Massachusetts. Autumnal blows from the northeast resulted in decidedly poor sea watching conditions, but strong west winds would occasionally bring in good numbers of sea ducks from the channel to take cover in the natural lee that Muskeget provides. Days that proved exceptional for the mainland parts of the state wound up being unequivocal busts for Tuckernuck. Other times, incredible migration would descend upon the Outer Lands, while the majority of coastal New England experienced little of the fallout. Interestingly, many of the exceptional days occurred in what would otherwise be so-called unexceptional conditions. Late August and early September proved to be a time filled with unusual potential and promise for all things rare.

A Yellow-throated Warbler of the southeastern coastal subspecies was observed on October 1, precursing a slew of southerly breeding species that would reach the island.

A standout example can be shown in the remarkable birding that took place on August 28, detailed in this checklist: <https://ebird.org/checklist/S72916460>. High counts on eBird for Purple Martin (10), Warbling Vireo (5), and Baltimore Oriole (24) in Nantucket County were broken that day, as well as unusually early records of Black-throated Blue Warbler, Ovenbird, Yellow-bellied Flycatcher, and Veery. Canada Warbler and Blue-winged Warbler remain scarce and undetected migrants on the Outer Lands, listed as very rare vagrant (four records) and casual (one record), respectively, in the 1948 historical anthology The Birds of Nantucket (Griscom and Folger 1948). These species may be slightly more abundant on Cape Cod, where the latter is believed to have nested in recent years; however, a lack of dedicated field observers on the islands during peak migration times may account for this disparity. As Griscom and Folger stated in 1948, “the island badly needs more experienced observers who can take the seabirds for granted, and who will be willing to spend their time looking for those birds whose status on Nantucket is not properly known,” (p. 14) and the same is still true today. Collection of long-term, comprehensive data for these trends must be ongoing and is necessary to create a complete picture of the true status of songbird migrants on Nantucket and Tuckernuck.

An adult Hudsonian Godwit flies over Whale Point on August 6, after lingering for nearly two weeks.

Several vagrants found this season on Tuckernuck highlight the role that small islands adjacent to larger land masses play as natural migrant traps with great potential for finding rarities, in keeping with other famed locales for birding like the Outer Tuskets, or the Heligoland archipelago of the North Sea. The first record of Gray Heron for the lower 48 states was found on Tuckernuck on September 5 and is believed to be the same bird that spent the summer along the north shore of Nova Scotia from June 28 through August 22 <https://ebird.org/checklist/S70918762>. The bird was subsequently found the next day on the nearby island of Muskeget, and from there, the bird’s whereabouts remain unknown. Two records in November of Gray Heron from coastal Virginia may perhaps be of the same individual but are equally likely to represent documentation of a wholly separate bird, perhaps a reflection of this species’s growing population in the Lesser Antilles, especially Barbados (Martínez-Vilalta et al 2020). There is not enough evidence from the photos alone to conclude that the Virginia and Massachusetts records represent the same bird.

This Gray Heron sighting in Tuckernuck and Muskeget is highly significant because it poses only the fifth record for the United States, and a first for the lower contiguous states. There are several recent records from Newfoundland, including one immature bird that landed on an oil rig 230 miles east of St. John’s, on September 30, 2018 <https://ebird.org/checklist/S68445110>. Subsequent records of young or hatch-year birds in 2018 at Renews (November 2 to November 13, <https://ebird.org/checklist/S49638955>), and Saint Lawrence (December 1 to December 7, <https://ebird.org/checklist/S52042640>), are likely to represent two or three separate individuals, but could also represent a single bird working its way west along the southern coast of Newfoundland, although this seems less likely. In Iceland, where this species is now a regular winter resident, birds presumably from Norway arrive in late August or early September and depart by late April or early May, with 2,670 records prior to 2011 (Petursson and Kolbeinsson 2016).

Pine Siskins, which alighted on the island by the hundreds this fall, began arriving as early as September.

Together with a warming climate and increased cultivation of rice in southern Europe, this species’s breeding range is spreading in much of Scandinavia, with some Gray Herons likely colonizing new areas for the first time ever. A population in the Cape Verde islands off the west coast of Africa is also believed to be increasing (Martínez-Vilalta et al. 2020). Taking into consideration that there are several populations of Gray Heron currently undergoing expansion, it would not seem correct to conclude that the Nova Scotia and Massachusetts individual arrived in the Canadian Maritimes from one set direction or the other. Historically, the popular notion has been that Old World wading species that arrive on the East Coast of the United States in springtime are drift migrants from sub-Saharan Africa that have used the transatlantic trade winds along the equator, and therefore have arrived in the Neotropics first before migrating north (Howell 2014). This theory has been applied to records of both Little Egret and Western Reef-Heron, as well as the colonization of Glossy Ibis and Cattle Egret in the Americas.

Tuckernuck also hosted for a brief period this fall a Swainson’s Warbler, which, pending acceptance, would make just a sixth state record. The bird was documented in detail on October 3 <https://ebird.org/checklist/S74378976>, and then seen again on October 11 in relatively the same area, although this follow-up report has not been submitted.

Five previous records exist for Massachusetts. One account from Dukes County on the island of Naushon, May 11, 2001, to June 6, 2001, (Maloney and Jones <https://ebird.org/checklist/S4819411> and <https://ebird.org/checklist/S48194>

and one record from Essex County at Plum Island, May 9, 2007, to May 29, 2007, (Pivacek <https://ebird.org/checklist/S17196906>) represent singing individuals during the early breeding season. The Plum Island bird was banded. The other three reports are of Barnstable County birds and include two spring records in early May 1982 (Young <https://ebird.org/checklist/S33225867>) and 2018 (Crosson <https://ebird.org/checklist/S45352134>) and one fall record of a bird caught in a mist net (September 6, 2010, to September 10, 2010, (Finnegan <https://ebird.org/checklist/S17524634>).

New York City reports no more than 20 records for Swainson’s Warbler ranging back to 1950, and all occurred during the months of April and May (Buckley et al. 2018). Recent records in our region include those from both northern Vermont <https://ebird.org/vt/checklist/S56722900> and Halifax, Nova Scotia, <https://ebird.org/checklist/S59704394>, the latter record being similar to the Tuckernuck record in the sense that both were fall occurrences with other southern wood-warbler species present.

Swainson’s Warbler is a habitat specialist, inhabiting the dense undergrowth of mixed deciduous woodland in the southeastern United States, where it is known to be a seldom-encountered and reclusive denizen of dead leaf beds and thorny, impenetrable thickets. Undoubtedly, records of this species are likely to go unnoticed during fall migration because of these behavioral factors; spring records consist primarily of singing birds located first by their ew ew stepped in poo song. Data from the North American Breeding Bird Survey over a 50-year period (1966–2015) show that the Swainson’s Warbler is a steadily increasing breeder over much of its key range, primarily along the Southeastern Coastal Plain that runs through the Carolinas and Georgia, with an average yearly increase of 1.91% in this area. This number is significant because it shows the largest margin of growth compared to other areas within this species’ range (cf. 1.48% increase in the Western Gulf Coastal Plain and -0.06% decrease in the Appalachians), and is the area with the greatest credibility interval (95%) and a sample size of 152 different Breeding Bird Survey routes (Anich et al. 2020). If these data are truly representative of an upward trend in these populations of Swainson’s Warbler, then a reasonable conclusion is that records in New England will continue to increase. The disparity between the numerous records in the Northeast of singing individuals in April and May compared to the mere five records north of the Mason-Dixon line between September and November indicates that this species is likely far less detectable as a migrant during fall than spring.

Other notable rarities from this season include a White-winged Dove from July <https://ebird.org/checklist/S71444558>, several Lark Sparrows ranging from August through October, a Yellow-throated Warbler of the coastal subspecies <https://ebird.org/checklist/S74287927>, a Prothonotary Warbler in October <https://ebird.org/checklist/S74422731>, and a tie for all-time state late date for Cerulean Warbler <https://ebird.org/checklist/S74211333>.

While I have focused much of this piece on my observations of landbird activity on Tuckernuck throughout the latter half of my stay, I should also make note of the increasing numbers of staging terns that can be found on both Whale and Bigelow’s points during the doldrums of midsummer. I spent many hours examining the composition of these loafing birds and reading plastic field-readable (PFR) leg and color bands. In all, eight species of tern were recorded on the island this year: Royal, Sooty, Least, Common, Roseate, Black, Forster’s, and Arctic. Although records of Sandwich Tern have been increasing on Tuckernuck, with the most recent record in 2018 (Ella Potenza, personal communication), none was found this year. According to Dr. Richard Veit, who studies tern colonies on Muskeget and Tuckernuck, the number of nonbreeding over-summering terns on the islands’ shoals continues to increase (Veit and Perkins 2014), which may be a reflection of declining populations elsewhere. An overwhelming majority of Roseate Terns this season on Tuckernuck were individuals from Buzzards Bay colonies and Great Gull Island, New York.

Future observers on Tuckernuck should not be reluctant to look inland for good birds, rather than automatically following the tried-and-true method of dropping everything and heading for the beach. In my experience, twit birding—a local term for birding for passerines—on Tuckernuck has proved to be far more rewarding than its seawatching. The concentrations of birds per square kilometer here are unparalleled by even Nantucket, and on occasion mixed flocks of 50 or more Neotropical migrants can be found working their way through the low cover of scrub oak and sassafras. However, please note that special permission from a landowner is required for gaining access to the island, and that rules involving camping, loose dogs, and noise are as applicable on Tuckernuck as they are on nearby Nantucket. The Tuckernuck Land Trust takes a key role in protecting and conserving the delicate nature of the island, both through stewardship and education programs. You can visit them online at <https://www.tuckernucklandtrust.org/>.

References

- Anich, N. M., T. J. Benson, J. D. Brown, C. Roa, J. C. Bednarz, R. E. Brown, and J. G. Dickson. (2020). Swainson’s Warbler (Limnothlypis swainsonii), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (P. G. Rodewald, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA.

- Anonymous. 2018. eBird Checklist: https://ebird.org/checklist/S68445110. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance [web application]. eBird, Ithaca, New York. Available: http://www.ebird.org. Accessed December 17, 2020.

- Berrigan, L. 2019. eBird Checklist: https://ebird.org/checklist/S59704394. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance [web application]. eBird, Ithaca, New York. Available: http://www.ebird.org. Accessed December 17, 2020.

- Berriman, T. 2019. eBird Checklist: https://ebird.org/vt/checklist/S56722900. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance [web application]. eBird, Ithaca, New York. Available: http://www.ebird.org. Accessed December 17, 2020.

- Brace, P. B. 2012. Nantucket: A Natural History. Nantucket, Massachusetts: Mill Hill Press.

- Buckley, P. A., W. Sedwitz, W. J. Norse, and J. Kieran. 2018. Urban Ornithology: 150 Years of Birds in New York City. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

- Carrière, M. 2020. eBird Checklist: https://ebird.org/checklist/S70918762. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance [web application]. eBird, Ithaca, New York. Available: http://www.ebird.org. Accessed December 17, 2020.

- Clarke, J. 2018. eBird Checklist: https://ebird.org/checklist/S49638955. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance [web application]. eBird, Ithaca, New York. Available: http://www.ebird.org. Accessed December 17, 2020.

- Crosson, P. 2018. eBird Checklist: https://ebird.org/checklist/S45352134. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance [web application]. eBird, Ithaca, New York. Available: http://www.ebird.org. Accessed December 31, 2020.

- Finnegan, S. 2010. https://ebird.org/checklist/S17524634. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance [web application]. eBird, Ithaca, New York. Available: http://www.ebird.org. Accessed December 31, 2020.

- Griscom, L. and E. V. Folger. 1948. The Birds of Nantucket. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Howell, S. N. G. 2014. Rare Birds of North America. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Kardell, S. 2020. eBird Checklist: https://ebird.org/checklist/S71444558. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance [web application]. eBird, Ithaca, New York. Available: http://www.ebird.org. Accessed December 17, 2020.

- Kardell, S. 2020. eBird Checklist: https://ebird.org/checklist/S74211333, eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance [web application]. eBird, Ithaca, New York. Available: http://www.ebird.org. Accessed December 17, 2020.

- Kardell, S. 2020. eBird Checklist: https://ebird.org/checklist/S74287927. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance [web application]. eBird, Ithaca, New York. Available: http://www.ebird.org. Accessed December 17, 2020.

- Kardell, S. 2020. eBird Checklist: https://ebird.org/checklist/S72916460. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance [web application]. eBird, Ithaca, New York. Available: http://www.ebird.org. Accessed December 17, 2020.

- Kardell, S. 2020. eBird Checklist: https://ebird.org/checklist/S74378976. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance [web application]. eBird, Ithaca, New York. Available: http://www.ebird.org. Accessed December 17, 2020.

- Kardell, S. 2020. eBird Checklist: https://ebird.org/checklist/S74422731. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance [web application]. eBird, Ithaca, New York. Available: http://www.ebird.org. Accessed December 17, 2020.

- Lazell, J. D. 1976. This Broken Archipelago: Cape Cod and the Islands, Amphibians, and Reptiles. New York, New York: Quadrangle/New York Times Book Co.

- Maloney, T. and A. Jones. 2001. https://ebird.org/checklist/S4819411. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance [web application]. eBird, Ithaca, New York. Available: http://www.ebird.org. Accessed December 31, 2020

- Maloney, T. and A. Jones. 2001. https://ebird.org/checklist/S4819412. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance [web application]. eBird, Ithaca, New York. Available: http://www.ebird.org. Accessed December 31, 2020.

- Martínez-Vilalta, A., A. Motis, and G. M. Kirwan (2020). Gray Heron (Ardea cinerea), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, J. Sargatal, D. A. Christie, and E. de Juana, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA.

- Petursson, G. and Y. Kolbeinsson. 2016. List of Icelandic Bird Species. Available online at https://notendur.hi.is/yannk/1111.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2020.

- Veit, R.R. and S. A. Perkins. 2014. Aerial Surveys for Roseate and Common Terns South of Tuckernuck and Muskeget Islands July–September 2013. US Dept. of the Interior, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Office of Renewable Energy Programs, Herndon, VA. OCS Study BOEM 2014-665. 13 pp.

- Walsh, L. 2018. eBird Checklist: https://ebird.org/checklist/S52042640. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance [web application]. eBird, Ithaca, New York. Available: http://www.ebird.org. Accessed December 17, 2020.

- Young, J. 1982. https://ebird.org/checklist/S33225867. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance [web application]. eBird, Ithaca, New York. Available: http://www.ebird.org. Accessed December 31, 2020.