Patrick Felker

The Great Swamp Management Area in South Kingstown, Rhode Island, is a 3,349-acre preserve that is rich with diverse habitats, history, and birds. You can access the walking trails from the dirt parking lot at the end of Great Neck Road (41.4690987646978, -71.5795471982134). To get to Great Swamp from Interstate 95, take exit 3A and merge onto RI-138 eastbound. After driving eastbound on RI-138 for 8.8 miles, make a sharp right turn onto Liberty Lane. TLC Coffee Roasters is located at this intersection.

The Great Swamp Management Area in South Kingstown, Rhode Island, is a 3,349-acre preserve that is rich with diverse habitats, history, and birds. You can access the walking trails from the dirt parking lot at the end of Great Neck Road (41.4690987646978, -71.5795471982134). To get to Great Swamp from Interstate 95, take exit 3A and merge onto RI-138 eastbound. After driving eastbound on RI-138 for 8.8 miles, make a sharp right turn onto Liberty Lane. TLC Coffee Roasters is located at this intersection.

To get to Liberty Lane from US-1, turn onto RI-138 westbound at the traffic light at (41.49477, -71.45652). After 5.2 miles, make a slight left turn onto Liberty Lane at TLC Coffee Roasters. To get to Great Swamp from RI-4, take exit 3B onto RI-102 northbound toward Exeter. Once on RI-102, turn left onto RI-2 southbound in 0.7 mile. Continue driving south on RI-2 for 6.8 miles, and turn left at the traffic light onto RI-138 eastbound. After 1.4 miles, take a sharp right turn onto Liberty Lane at TLC Coffee Roasters.

After turning onto Liberty Lane, continue straight for 0.8 mile. Soon Liberty Lane curves to the left, runs parallel to the railroad, and becomes Great Neck Road, which is an unpaved road usually littered with potholes. In 0.5 mile, there will be a hunter check station and the Department of Environmental Management offices on the right; continue straight. Soon after entering the forest, continue past the gun range on the left. About 100 feet after the gun range turnoff, there will be a misleading sign posted to a tree that says “Authorized Vehicles Only.” This sign is not in reference to Great Neck Road but is in reference to a side “road” that is overgrown and unrecognizable. Keep driving on Great Neck Road for another 0.3 mile until you reach a large clearing, which is the parking lot for Great Swamp Management Area. The gate at the end of the parking lot is where the walk begins.

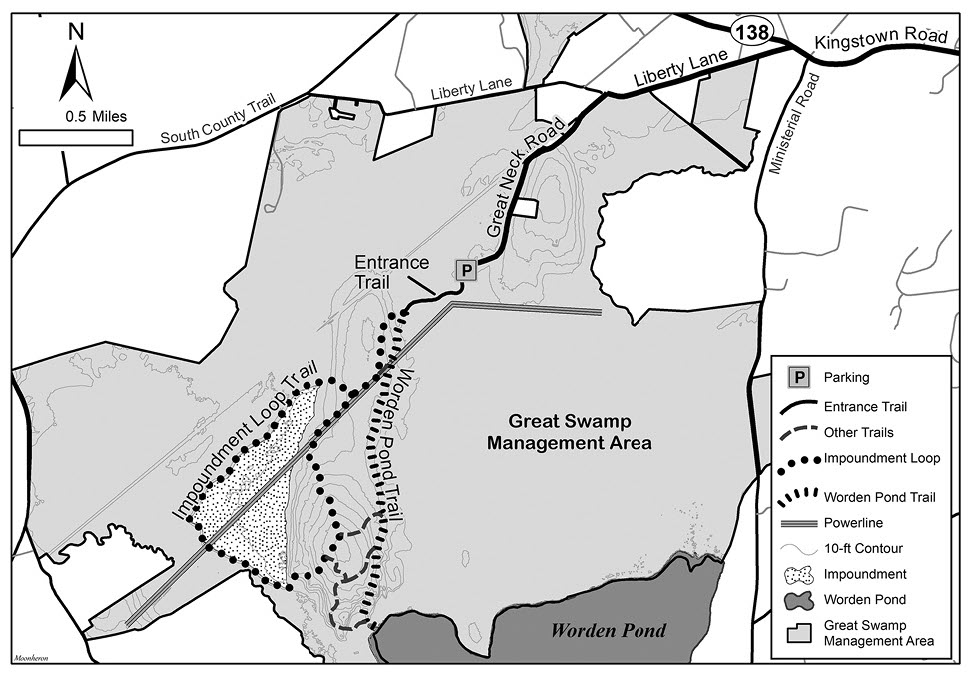

Map 1. Great Swamp Management Area.

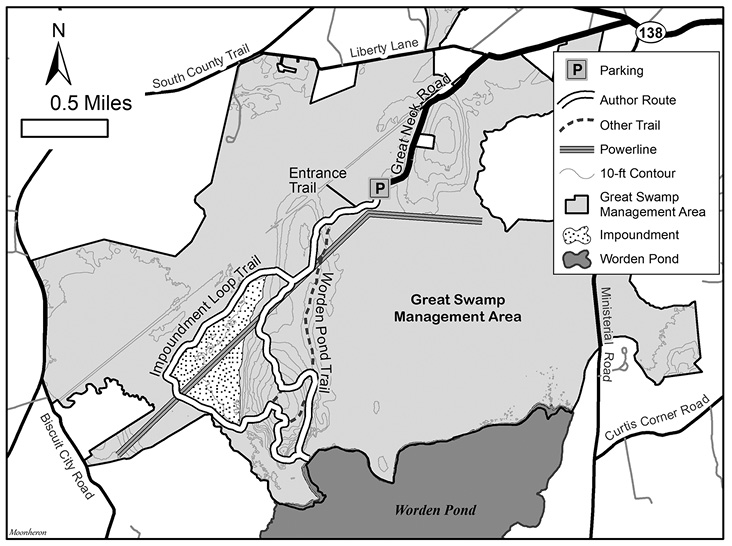

Map 2. Patrick’s Favorite Birding Route.

Great Swamp is free to the public, including hunters, so there are some important rules pertaining to hunting season. In Rhode Island, hunting season in management areas is permitted from the second Saturday in September to February 28, and the third Saturday in April to May 31. During hunting season, wearing fluorescent orange is required, and the Environmental Police strictly enforce these laws at Great Swamp. For most of the hunting seasons, at least 250 square inches of fluorescent orange is the amount required, which is either a hat or a vest. However, during the month of December, at least 500 square inches of fluorescent orange is required; you must wear a hat and a vest. All the hunting regulations for state management areas are at this link: <http://www.dem.ri.gov/programs/bnatres/fishwild/pdf/huntabs.pdf>. Another rule of Great Swamp is that all dogs must be on a leash unless they are being used for hunting. An important note is that Great Swamp is open from sunrise to sunset. The entire list of parks and recreation regulations can be found at this link: <https://rules.sos.ri.gov/regulations/part/250-100-00-1>.

Historically, Great Swamp was the site of a pivotal tragedy for local indigenous peoples. When English settlers arrived in Rhode Island in the mid-1600s, the Narragansett Tribe occupied most of the land throughout the state, including Great Swamp. As more and more settlers arrived, pressure mounted on the Narragansett Tribe to trade land for products. These trades were often one-sided and mostly benefited the colonists. Slowly, the Narragansett Tribe’s land shrank until it was just a chunk of southern and western Rhode Island, with Great Swamp at the heart of it. Great Swamp was a large village with more than 1,000 Narragansett men, women, and children.

On June 20, 1675, a war known as King Philip’s War began between the Wampanoag Tribe and the Massachusetts Bay Colony. The Narragansett Tribe, valuing peace, tried to stay neutral but sheltered Wampanoag women and children. In the minds of the colonists, sheltering Wampanoags was an act of war. As a result, members of the militias of the Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, and Connecticut colonies staged at Smith’s Castle in Wickford, Rhode Island, in preparation for an attack on Great Swamp. On December 19, 1675, the combined colonial army crossed the frozen swamp and set fire to the village, killing more than 1,000 Narragansett men, women, and children. This attack became known as the Great Swamp Massacre and tragically marked the end of the dominance of the Narragansett Tribe in southern Rhode Island. The exact site of the massacre is kept a secret and, therefore, is not close to or accessible by any trails. There is a monument dedicated to the Great Swamp Massacre at the end of Great Swamp Monument Road, off RI-2, about a mile south of the intersection of RI-2 and RI-138. There are no trails here that connect with the rest of the management area.

An American Kestrel perches on a dead tree at the second swamp opening along the Entrance Trail. All photographs by the author.

After the massacre, Great Swamp was unused because the swampy land was not conducive to farming. In the 1950s when creating wildlife habitat was becoming more prominent, Great Swamp was purchased using Wildlife and Sport Fish Restoration Funds to transform the land into a wildlife management area. These funds, along with revenues received through a tax on firearms, ammunition, and archery equipment, were used to convert a large tract of boggy wetland into a large impoundment, accessible by the main trail at the western end of the management area. This impoundment was created to attract waterfowl for hunting. Currently, the management area has a variety of uses, including a gun range, various kinds of hunting, and other types of outdoor recreation such as hiking and birding.

Bird biodiversity at Great Swamp is highest during the spring, summer, and fall. Therefore, this article will cover the birds you may expect to find at different parts of Great Swamp during those seasons. Great Swamp is home to a host of mosquitos, black flies, deer flies, and deer and dog ticks. To avoid the ticks, try to stay on the trail and thoroughly check yourself for ticks when you get home. Overall, to maximize bird counts and minimize bug bites, the best months to bird Great Swamp are May and September. If you end up birding Great Swamp during the peak summer months, try to time your trip for a cloudy or even slightly rainy day, since deer flies and black flies avoid such weather, though mosquitos will still be around. The best time of day to bird during the summer months is as early as possible. It is optimal to arrive at Great Swamp when it opens at sunrise to hear the greatest number of birds singing.

View of the Atlantic white cedar swamp in summer from the powerline cut.

Because the impoundment is fresh water, there is no need to consider the tide when planning a trip to Great Swamp. There is a variety of walking trails at Great Swamp, but the trails do not have official names. For this article, I have given the trails descriptive names. (See Map 1. Great Swamp Management Area.) I call the trail that begins the walk the Entrance Trail. Only 0.3 mile long, it is short but beautiful, with a scenic vista of an Atlantic white cedar swamp. You can bird this trail fully in about 30 minutes. The Entrance Trail ends at a fork. The Worden Pond Trail continues straight and is about 2.86 miles to Worden Pond and back; it takes approximately two hours to bird. Veering right at the fork leads you onto the Impoundment Loop Trail. This loop is about 3.7 miles long, and you can bird it in three to four hours. Along the Impoundment Loop and Worden Pond trails are several cut-through trails that connect the two trails, so it can be fun to combine both trails while birding Great Swamp, which is what I do. My favorite route is about six miles long and can take close to five hours to complete. (See Map 2. Patrick’s Favorite Birding Route.) I highly recommend this route if you are looking for a long, peaceful birding trip. Great Swamp is rich with nature and biodiversity on all of the trails.

Black-and-white Warbler along the Impoundment Loop Trail.

Entrance Trail

Before starting out on the Entrance Trail, take a walk around the parking lot and listen closely. The trees around the parking lot area are mostly red maple, white oak, and northern red oak. Hooded Warblers nest in the mountain laurels on the northeast side of the parking lot, and this is a good place to listen for their song. Northern Parulas also can be found in this area. Great Swamp has the largest concentration of breeding parulas in Rhode Island. For a long time, Great Swamp was the only place in the state where they bred, but they are expanding to other forests in southern Rhode Island. West of the parking area, you can hear the descending song of the Northern Waterthrush, as well as the melodic songs of Veeries.

When you start walking beyond the gate, you will see the many Red-winged Blackbirds and Common Grackles that inhabit this part of the swamp. In early to mid-spring, keep an eye and ear out for Rusty Blackbird in this flock as well. Other birds in this area are Common Yellowthroat, Ovenbird, American Redstart, Black-and-white Warbler, Red-eyed Vireo, and Yellow-throated Vireo. These birds also inhabit many other parts of Great Swamp.

Shortly, you will arrive at an opening with many dead trees on your left, where the blackbirds are almost a constant sight. Sometimes American Kestrels use the tops of these trees as hunting perches. Swamp Sparrows can be found here year-round. Walk through another small patch of forest for about 300 feet, and you will arrive at a larger opening on your left—an Atlantic white cedar swamp. Swamp Sparrows reside in the cedar swamp all year, and blackbirds, Tree Swallows, and Yellow Warblers nest there. On your right, listen closely for Northern Waterthrushes singing. As you continue along the trail, you will see a small pond on the right where Northern Waterthrushes sometimes feed. Near the forest you may hear or see a vibrant Scarlet Tanager.

A Broad-winged Hawk soars over the first field of the Impoundment Loop Trail.

Once you enter the forest, the Entrance Trail ends in a fork. Hiking straight will lead you to Worden Pond, the largest freshwater body of water in Rhode Island, while veering to the right will lead to a powerline cut and the Impoundment Loop Trail. The Impoundment Loop Trail is usually more productive for birds, so that is the trail highlighted first.

Impoundment Loop Trail

When you head out on the Impoundment Loop Trail, listen for Pine Warblers singing in the assortment of conifers here, which include eastern white pine, pitch pine, Norway spruce, eastern hemlock, and red cedar. As you continue, you may start to smell a foul odor coming from the shed (slightly visible on your left) that contains the remains of dead animals. Mostly deer decay inside, but whale carcasses have been disposed of in Great Swamp, too. Soon, a field opens on your right that is home to Eastern Bluebirds and Field Sparrows; the woods on the other side of the field host breeding Northern Parulas. The field is also a good place to see Broad-winged Hawks soaring. Approximately 0.2 mile from the field, the trail will join a powerline cut that attracts many woodland edge birds and is also a migrant trap during spring and fall migrations. During the breeding season, Eastern Bluebird, Field Sparrow, Eastern Towhee, Gray Catbird, Eastern Kingbird, White-eyed Vireo, Blue-winged Warbler, Yellow Warbler, and Chestnut-sided Warbler live here. During fall migration, the small, overgrown field to the right of the powerline where the trail veers right can hold the elusive Connecticut Warbler.

A Black Vulture soars overhead.

Where the trail meets the powerline cut, walk a little more than 0.1 mile until you reach another intersection. This part of the trail is a loop, so it does not matter if you continue straight or turn right. Going straight will take you along the powerline cut for a little bit longer and then to open uplands interspersed with trees. In approximately 0.3 mile, the powerline cut diverges from the main trail; follow the main trail slightly left for almost 0.4 mile to the upland area of Great Swamp. Many types of shrubs grow here, interspersed with American holly trees; Great Swamp has the largest concentration of American holly trees in Rhode Island, contributing to the diversity of wildlife here. This area is a good spot for many of the powerline cut birds that I have already mentioned, as well as Indigo Bunting and sometimes Prairie Warbler. One year, a Yellow-breasted Chat made this area its territory, singing frequently to attract a mate. It is unknown if the breeding attempt was successful because observers saw only one Yellow-breasted Chat at a time. This area is ideal for swallows, as evidenced by the breeding Tree Swallows. It is a good spot for viewing early Purple Martins in April. This overlook gives you a panoramic view of the Great Swamp impoundment and the many Osprey nests that dot the powerlines.

In about 0.1 mile, you will come to another fork in the trail. To follow the Impoundment Loop, turn right at this fork and walk straight until you see an opening on your right. Eastern Bluebirds nest in this field, and on the far end is a stand of gray birch trees. Past the field you will enter a forest and follow the trail down the hill for about 0.4 mile. This wooded area can be a good spot for Winter Wren in winter and early spring and Blue-gray Gnatcatcher in the breeding season.

Wilson’s Snipe forages on the impoundment.

At the bottom of the hill, the trail emerges from the forest next to a large impoundment on the right. The Department of Environmental Management (DEM) controls the water levels in this impoundment using a large underwater pipe to drain water into the forested swamp nearby. DEM controls the water level seasonally to attract birds. In winter, the impoundment holds as much water as possible to attract ducks and geese for waterfowl hunting season. Starting in late March, it is drained to expose mudflats for migrating shorebirds such as Least Sandpiper, Greater and Lesser yellowlegs, and Pectoral Sandpipers to feed. Spotted Sandpipers and Killdeer inhabit the impoundment throughout the summer. If the water levels are low, the impoundment usually has Glossy Ibis, Great Egret, and Great Blue Heron. The impoundment is the most reliable place for Wilson’s Snipe in the state, with many migrating through and some possibly breeding here. Snipe at Great Swamp had a particularly good year in 2018, with a count of 52 snipe one day in early April.

The impoundment also hosts ducks such as Green-winged Teal and sometimes Blue-winged Teal; on rare occasions, Northern Shovelers migrate through. It is worth watching for raptors at the impoundment, where Bald Eagle, Turkey and Black vulture, Osprey, Cooper’s Hawk, American Kestrel, Broad-winged Hawk, and Red-tailed Hawk often soar overhead. Checking all the Osprey nests sometimes results in seeing Great-horned Owls, since they have been known to use Osprey nests to hatch and raise chicks. King Rails have visited the impoundment in the past, but not since 2016. Warbling Vireo, American Redstart, Yellow Warbler, Common Yellowthroat, Swamp Sparrow, Northern Waterthrush, and Orchard Oriole are found on the forested side of the trail.

Eastern Bluebird perches on a nest box.

Other wildlife found in the impoundment include beavers and snapping turtles. It can take a long time to walk around the impoundment, but it is well worth it to go slowly and scan the water and shrubs for hidden birds. The trail parallels the impoundment for just under 1.5 miles. When the trail leaves the impoundment, it goes through a forest containing oak, beech, and yellow birch where you may find Northern Parulas, Black-and-white Warblers, and American Redstarts. In 0.15 mile, you will return to the trail intersection at the powerline cut, which marks the completion of the Impoundment Loop. Return to the Entrance Trail.

Worden Pond Trail

The other trail at the end of the Entrance Trail leads straight to Worden Pond. This trail begins at a section of woodland that is home to Downy and Hairy woodpecker, Eastern Wood-Pewee, and Great-crested Flycatcher. Pileated Woodpecker also can be found in this area, but not reliably. Follow the Worden Pond Trail for about 0.2 mile to the powerline cut, which you will cross to head straight to Worden Pond. However, if you want to get a view of the Atlantic white cedar swamp from the back, you can detour left along the powerline cut for about 0.7 mile. Be careful not to go much farther down this powerline trail because it gets close to the back of the gun range. The Department of Environmental Management stocks Ring-necked Pheasants around this powerline cut. Because they are stocked and are not naturally occurring, they are not countable on any official lists. The only place in Rhode Island where Ring-necked Pheasants are countable is on Block Island.

Return to the Worden Pond Trail where you will notice a multitude of American holly trees surrounded by other shrub species. Here you may encounter American Redstart, White-eyed Vireo, and Northern Parula. In 0.7 mile you will come to a fork in the trail; continue straight and arrive at Worden Pond in 0.5 mile. (Veering right at this fork will take you to the Impoundment Loop in the open upland area.) As you walk to Worden Pond, keep an eye and ear out for the flat, buzzy trill of Worm-eating Warbler on your left; there has been a male singing in this area during the breeding season for the past few years. Pine Warblers also breed along this portion of the trail. Eastern Phoebes and Northern Waterthrushes breed closer to Worden Pond. At the pond you can spot Wood Ducks and Belted Kingfishers flying. Sometimes a massive flock of gulls—mostly Herring Gulls—feeds in the air above Worden Pond.

From Worden Pond you have several options. Taking the short trail west of the gray slab of concrete at the end of the Worden Pond Trail will lead to the Impoundment Loop Trail. The second option is to return the way you came to the parking lot. Or instead of backtracking all the way, you can take one of the various connecter trails to the Impoundment Loop Trail and head back from there.

Patrick’s Favorite Birding Route

All the trails at Great Swamp have their own beauty and array of birds, which is why I like to combine the Impoundment Loop and the Worden Pond trails using the short connecter trails between them. This is my route: at the end of the Entrance Trail, follow the Impoundment Loop Trail for 0.5 mile to the loop intersection. Keep going straight at the fork by the powerline cut, then veer left to stay on the Impoundment Loop Trail in order to bird the upland part of this trail. In just over 0.7 mile, you will come to an intersection with a connector trail. Go straight for 0.2 mile to follow this connecter trail from the Impoundment Loop Trail to the Worden Pond Trail (turning right would keep you on the Impoundment Loop Trail). Turn right on the Worden Pond Trail, and continue for 0.5 mile until you reach the gray slab of concrete. Follow the connector trail west of the concrete slab up the hill where it joins the Impoundment Loop Trail in 0.3 mile. Walk 2.38 miles to finish the Impoundment Loop Trail, and then take the Entrance Trail back to the parking lot. It is about six miles and can take close to five hours to complete.

Overall, there is no wrong way to bird Great Swamp; it is a wonderful place to bird no matter which trails you follow, and I recommend exploring Great Swamp to its fullest. For the birder who has an interest in both history and ecology, Great Swamp is an ideal place to bird.

Patrick Felker is a 20-year-old avid birder from North Kingstown, Rhode Island. He is currently in his junior year at the University of Rhode Island, studying Wildlife and Conservation Biology. Great Swamp is one of the first places Patrick went birding nine years ago, and it continues to be one of his favorite spots in Rhode Island.