Lisa Schibley

A mixed flock of shorebirds at Monomoy NWR. Photograph by Alan Kneidel.

In the early 1970s, Manomet biologist Brian Harrington was pondering important questions of shorebird migration and population biology. The shorebirds he was considering were those that nested in the high arctic tundra and then passed through North America, following the sun to winter in South and Central America. The puzzle was that the places where shorebirds spent the majority of their time, both north and south, were often remote and logistically complex for shorebird scientists to access. So how could scientists, with limited funding, best document population sizes and trends for these long-distant migrants? Brian hypothesized that a dedicated and enthusiastic group of shorebirders across the Western Hemisphere could, by counting shorebirds on their migration routes, supply necessary data to shorebird scientists and conservation partners. This network of volunteers evolved into Manomet’s International Shorebird Survey (ISS), one of the longest-running citizen science projects in the world.

For more information, visit manomet.org.

Brian began recruiting for the ISS in 1974 and by 1980 he had recruited over 100 shorebird enthusiasts at 240 sites who were sending in more than 2,000 surveys by hand each year, including more than 200 surveys per year from South America. In New England, about 25 contributors were sending in counts from 39 sites. Some of the New Englanders that Brian recruited in those first years, and who continued to submit counts for decades, will be familiar to birders in New England, e.g., Rick Heil, Seth Kellogg, Rey Larsen, Blair Nikula, Wayne Petersen, and Soheil Zendeh. Brian also reached out to state and federal biologists in the area to encourage them to incorporate the ISS into work plans, successfully partnering with many organizations. Lindsay Tudor, who was the shorebird biologist for the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife for 30 years before recently retiring, is responsible for more than 10,000 ISS counts through her incredible army of volunteers along the Maine coast. And Nancy Pau, the wildlife biologist for the Parker River National Wildlife Refuge (NWR), has overseen a team of biological technicians who have been responsible for hundreds of ISS submissions over the years from one of the most important shorebird sites in New England.

Justin Barrett, Lisa Schibley, and Nate Marchessault conduct an ISS survey on Plymouth Beach, Massachusetts. Photograph by Brad Winn.

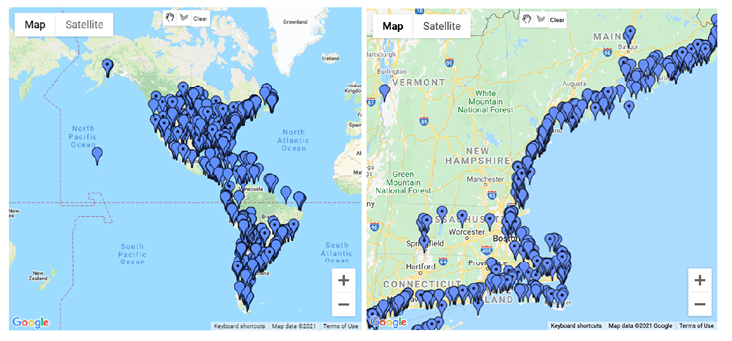

Of course, when the ISS began, there was no internet or eBird to facilitate data collection. Figure 1 shows an example of one set of surveys conducted by Wayne Petersen at Third Cliff in Massachusetts. At the end of each season these sheets were mailed to Manomet, where the numbers were entered by hand into a database for tabulation and analysis. In 2006, Brian moved the data entry process from handwritten documents to eBird, and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology has been a valuable partner for the ISS ever since. By 2020, the ISS had 455 contributors sending in about 5,000 surveys from 4,802 sites in 21 countries across the hemisphere. Figure 2 shows the extent of ISS sites, both historical and current, in New England and across the Western Hemisphere, taken from the ISS Mapping Tool (https://www.manomet.org/iss-map/).

.jpg?ver=wsMhIv3dCyzJWZpuFCP4nw%3d%3d)

Figure 1. One of the early ISS forms.

From the beginning, the International Shorebird Survey produced important results to help understand populations and trends. After the first ten years of data collection, Marshall Howe of the US Fish and Wildlife Service published “Population trends of North American shorebirds based on the International Shorebird Survey” (Howe 1989), one of the first studies showing a statistically significant decline for some migrating shorebird species. Howe also suggested a number of ways that the ISS could be improved, particularly emphasizing the need for consistency in coverage across the years.

Significant results for shorebird population estimates and trends using ISS data were also published in 2006 (Morrison 2006), 2007 (Bart 2007), and 2012 (Andres 2012). The ISS is also a source of data for the North American Bird Conservation Initiative (https://nabci-us.org), which annually publishes a “State of the Birds” report (www.stateofthebirds.org) detailing declines in birds that use the coastal ecosystems—which includes most, although not all, shorebirds.

Figure 2. Extent of ISS sites, both historical and current, in New England and across the Western Hemisphere, taken from the ISS Mapping Tool (www.manomet.org/iss-map/).

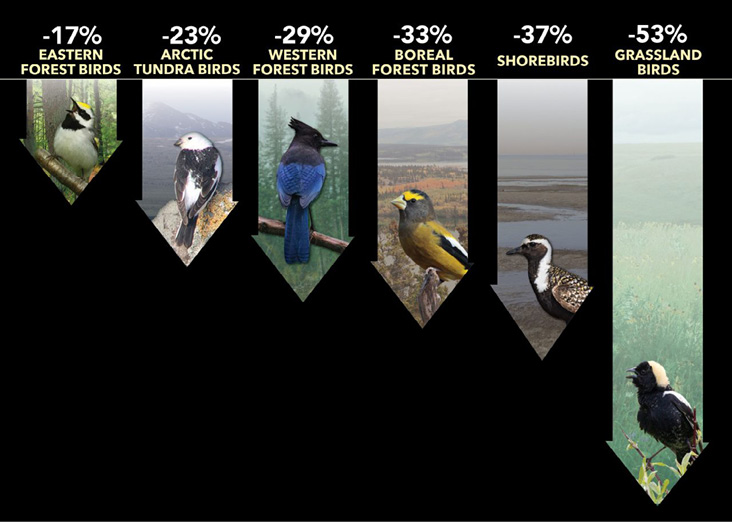

Most recently ISS data were used in the “3 Billion Birds” study that was published in 2019. This study showed that overall bird populations in the United States and Canada have declined by 29%, or almost three billion birds. The researchers analyzed the overall losses group-by-group, with some families showing steeper losses than others (Figure 3). The study’s lead author, Ken Rosenberg, Applied Conservation Scientist at Cornell University and American Bird Conservancy, shared with Manomet how important the ISS was for the shorebird results:

Because most shorebirds breed too far north to be monitored by the Breeding Bird Survey and winter well south of traditional coverage by Christmas Bird Counts, we relied on migration counts from the International Shorebird Survey for the most complete and reliable estimates of continental population trends for 20 shorebird species. Based on a comprehensive statistical analysis of ISS data from 1974 to 2017, co-author Paul Smith of Environment and Climate Change Canada determined that 11 of these species have declined by 50% or more since 1974, contributing to an overall loss of 37% across all shorebird species.

Figure 3. The 3 Billion Birds campaign used ISS data to show declines in shorebird populations.

The result of the study, the loss of three billion birds, captured the public’s attention in a way few scientific studies have. Cornell and other contributors created a compelling set of stories, videos, and infographics that were picked up by the press to an astonishing extent. They recorded 1,800 print media articles with a circulation of four billion people describing the impacts of the loss of these birds on ecosystems and how humans are changing the environment. The 3 Billion Birds campaign also did an excellent job of presenting seven simple actions every person can take to help birds. And of course, we were grateful to see that #7 is to contribute to a citizen science project to record and share your bird observations, with the International Shorebird Survey listed as one of the examples.

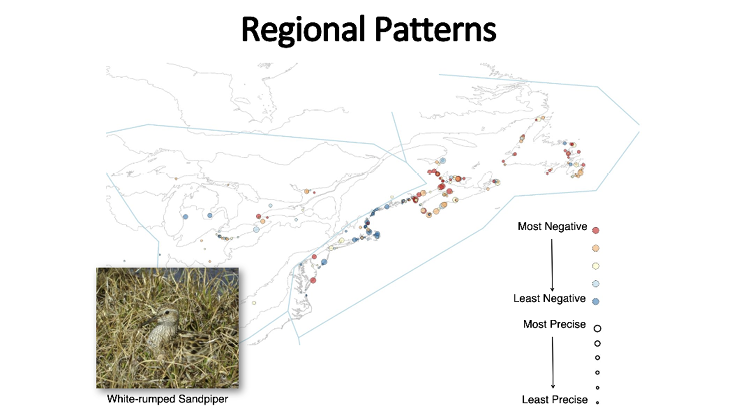

Environment and Climate Change Canada’s Paul Smith, one of the lead authors of the 3 Billion Birds study, has researched trends in shorebird populations using ISS data for more than 10 years. Last year, for the All About the ISS Webinar (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aQIdEhfmbL4), he shared one of his graphics summarizing ISS data for White-rumped Sandpiper (Figure 4). The map represents count data as circles, with the most negative trends as red and the least negative trends as blue. The map also represents the precision of the data by the size of the point, giving an overall snapshot for the northeast region including New England. The results seem to show that shorebird population trends in New England are not quite as negative as those in Maritime Canada.

Figure 4. Population trends for White-rumped Sandpiper using ISS data.

In addition to understanding broad hemispheric population trends, one of the most important uses for ISS data to identify important stopover sites. For example, ISS data and surveys were integral to the creation of the Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network (WHSRN) and are frequently used to support the nomination of new sites. WHSRN is a science-based, partnership-driven, conservation initiative for protecting critical sites for shorebirds throughout the Americas. The first WHSRN site, designated in 1985, was Delaware Bay. The Network today includes 111 sites in 18 countries, covering 39 million acres of shorebird habitat (Figure 5). There are two WHSRN sites in New England: Great Marsh, which includes Parker River NWR, and Monomoy NWR at the elbow of Cape Cod. Both were established with the help of ISS data.

As the ISS became established as an important protocol for monitoring shorebird populations, partners began to rely on it to supply data necessary for conducting management, conservation, and research at local scales. National Wildlife Refuges have included ISS data in their management priority-setting documents, such as the Monomoy NWR Comprehensive Conservation Plan published in March 2016. ISS data have been used by states developing conservation regulations and State Wildlife Action Plans. State and federal biologists also use the data to quantify and understand local issues. For example, Lindsay Tudor told us that “ISS data collected by Maine volunteers plays an integral role in identification and conservation of shorebird areas along Maine’s coast” (Tudor 2000). And Kate O’Brien, wildlife biologist at the Rachel Carson NWR in Maine, mentioned that the ISS “has been very helpful to us when documenting important shorebird roost and foraging areas allowing us to improve our conservation of these important areas and forming the basis for future studies” (Holberton 2019).

Figure 5. Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network (WHSRN) sites.

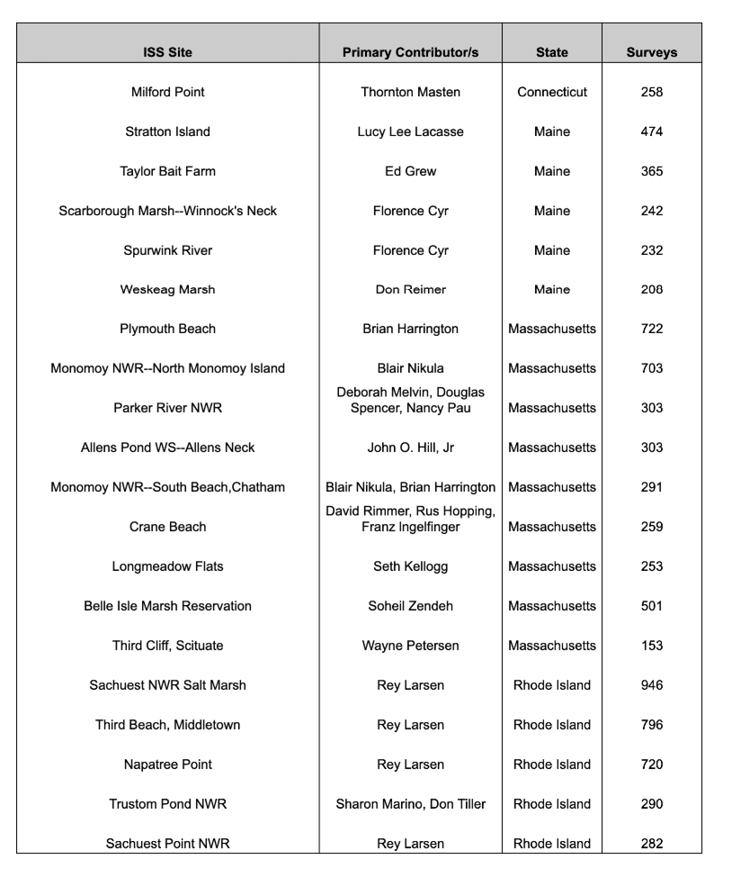

In addition to contributing to estimations for population sizes and trends of migratory shorebird species, identifying important stopover sites, understanding migration routes, contributing to local research, and supporting partners conducting management and conservation, Manomet’s International Shorebird Survey has one more extremely important goal: to build a broad constituency supporting shorebird monitoring and conservation. From the beginning, Brian knew shorebirds often inspire a particular passion. Some of the volunteers he originally recruited have submitted hundreds or even thousands of counts. Figure 6 lists some of the most prolific ISS contributors in New England and the sites they have covered. We recently contacted some of our most dedicated contributors for insight into their experience with the ISS and were grateful to hear back from so many.

Linda Pivacek wrote, "I was amazed and moved by the numbers of shorebirds that appeared in late summer near my Nahant, Massachusetts, home. Often, in early evening, I would watch them as they rested with bills in the sand on the empty beach; they were so exhausted. While researching these remarkable birds and their incredible journey during migration, I learned about Manomet’s ISS and in 2004 began my official surveys and continue to do so today."

Ed Grew from Maine wrote, “I have such fond memories of the days searching for and counting shorebirds. They remain my favorite birds. The Taylor Bait Ponds in Orono, Maine, were often drained, and the exposed mudflats were a big draw for migrating shorebirds. I contributed to ISS until bait farming at Taylor was discontinued and the ponds not drained.”

Sebastian Jones shared quite the story about a Buff-breasted Sandpiper running around a Jamaica Plain golf course “practically through the feet of a group of guys on a putting green” and then continued, “What gets me excited about the ISS is that it helps us see the bigger picture and allows birders and citizen scientists to contribute to that effort, especially at a time when many of these birds are in severe decline.”

Figure 6. Some prolific ISS contributors in New England.

And from Soheil Zendeh:

I was excited in 1976 when I first heard that Brian Harrington at Manomet was collecting shorebird data. I had been watching shorebirds along the Boston shore for a few years and had all my observations recorded on big sheets of graph paper. I arrived at Brian’s office and showed off my data tables. I think he was quite amused. Of course, he then told me exactly how he needed all my information organized—by site and on individual sheets. Thus started my collaboration with ISS.

Max Chalfin-Jacobs near a mixed shorebird flock at Monomoy NWR. Photograph by Lily Morello.

Brian Harrington and Alan Kneidel conduct an ISS survey at Monomoy NWR. Photograph by Brad Winn.

Wayne Petersen wrote:

Periodically, individuals come up with ideas, schemes, or protocols that literally move the conservation dial in ways that are beneficial to conservation planners and amateur field naturalists. The International Shorebird Survey (ISS) is just such a program. Brian Harrington, senior shorebird biologist at the Manomet Bird Observatory from1972 to 2007, is just such an individual. In 1975, Harrington and a collaborative of colleagues established what has become one of the most important shorebird monitoring programs in the world. Using data gathered by hundreds of volunteer observers from Canada to the Caribbean and southern South America, seasonal knowledge of shorebird distribution and abundance has made possible the recognition and establishment of many dozens of protected shorebird stopover sites and wintering areas that are essential to the survival of many increasingly beleaguered populations of shorebirds throughout the western hemisphere.

Brian Harrington’s and my friendship and our shared interest in shorebirds grew during mutual associations at the Manomet Bird Observatory. As Brian’s career interests increasingly focused on shorebird migration, especially that of Semipalmated Sandpipers and Red Knots, we regularly swapped stories of counting shorebirds at various coastal localities. By the mid-1970s, it was inevitable that Brian would ask me to become an ISS volunteer observer. For several years, I systematically counted shorebirds on a regular basis at localities as removed as Newburyport Harbor, Third Cliff in Scituate, Plymouth Beach, and Monomoy Island on Cape Cod.

Over time, I recognized the connectivity between important shorebird sites in Canada, New England, the Mid-Atlantic States, and eventually Central and South America. As our understanding of international shorebird movements expanded, I increasingly appreciated the significance of the seasonal counting and monitoring efforts of other volunteers like me. With the gradual designation of important internationally recognized ISS shorebird sites, my own infatuation with shorebirds became galvanized into a lifelong obsession. It gives me great pride to realize that my early efforts to systematically count local shorebirds has contributed to the evolution of an internationally recognized conservation program that today addresses the needs of a group of birds in dire need of international conservation.

For anyone interested in becoming an ISS contributor, simply pick a site near you that hosts shorebirds, visit your site regularly, identify and count the shorebirds that are there, and submit your data through eBird. We ask potential contributors to use https://www.manomet.org/iss-map/ to verify your site isn’t currently covered. Select your state and recent years, then zoom to your area to see which sites are currently covered. As an added bonus, you can look for sites that have been covered historically but are not now. The ability to compare your data to historical data will give your data added value.

International Shorebird Survey Logo.

After finishing your eBird checklist, select “International Shorebird Survey” under “Observation Type,” and then submit as normal. The most important components of the ISS protocols are repeated surveys within a migration season and repeatability. While the protocol documentation covers these items in more detail (https://www.manomet.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/ISS-Protocols_April2019.pdf), the summary is: Visit your site at least three times per migration season, though we encourage visits every ten days if that is manageable for you. Visit your site, in the same way, each time, meaning that you should cover the same area in about the same amount of time at about the same tide or disturbance conditions each visit. For more information please visit https://www.manomet.org/project/international-shorebird-survey/ or reach out to Lisa Schibley, ISS Coordinator for North America, at lschibley@manomet.org.

Please allow all of us on the ISS team to express our gratitude to everyone who is contributing ISS counts in New England and across the hemisphere.

From Brad Winn, Vice President, Resilient Habitats at Manomet and Director of the ISS since 2008:

We are deeply grateful for the volunteers and professional biologists counting shorebirds for the ISS. They make a tremendous effort to get out to their sites on a repetitive basis and submit their data through eBird. We hope they know the importance of their work and the value of their surveys for conservation initiatives. Citizen science remains one of the greatest methods for widespread monitoring efforts we’ve got, so anyone interested in making a difference the next time they feel like heading out to walk in their favorite shorebird spot, please consider doing so on behalf of ISS. What you consider a hobby could contribute to the next big shorebird science discovery.

And from Paul Smith:

Without dedicated survey participants, and without Manomet’s longstanding leadership, there would be no national shorebird monitoring program in the United States. The ISS is the key monitoring data set for shorebirds in North America. As people faithfully head out to shorebird stopover sites to participate year after year, and in some cases decade after decade, it is important that they recognize just how significant their contribution is.

References

- Andres, B. A., P. A. Smith, R. I. G. Morrison, C. L. Gratto-Trevor, S. C. Brown, and C. A. Friis. 2012. Population estimates of North American shorebirds, 2012. Wader Study Group Bulletin 119 (3):178–194.

- Bart, J., S. Brown, B. Harrington, and R. I. G. Morrison. 2007. Survey trends of North American shorebirds: population declines or shifting distributions? Journal of Avian Biology 14:18–24.

- Holberton, R. L., P. D. Taylor, L. M. Tudor, K. M. O’Brien, G. H. Mittelhauser, and A. Breit. 2019. Automated VHF Radiotelemetry Revealed Site-Specific Differences in Fall Migration Strategies of Semipalmated Sandpipers on Stopover in the Gulf of Maine. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 7:327.

- Howe, M. A., P. A. Geissler, and B. A. Harrington. 1989. Population Trends of North American Shorebirds Based on the International Shorebird Survey. Biological Conservation 49:185–199.

- Morrison, R. I. G., B. J. McCaffery, R. E. Gill, S. K. Skagen, S. L. Jones, G. W. Page, C. L. Gratto-Trevor, and B. A. Andres. 2006. Population estimates of North American shorebirds, 2006. Wader Study Group Bulletin 111:67–85.

- Rosenberg, K. V., A. M. Dokter, P. J. Blancher, J. R. Sauer, A. C. Smith, P. A. Smith, J. C. Stanton, A. Panjabi, L. Helft, M. Parr, and P. P. Marra. 2019. Decline of the North American avifauna. Science 366:120–124.

- Tudor, L. 2000. Migratory Shorebird Assessment. Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife. 67 pp. Available online at https://www.maine.gov/ifw/docs/migratory-speciesassessment.pdf Accessed August 10, 2021.

Lisa Schibley joined the Shorebird Recovery Program at Manomet in 2008 and is currently the North American coordinator for the International Shorebird Survey. She develops and maintains the online ISS mapping tool, creates reports for Manomet scientists and partners, recruits and engages ISS volunteers through social media and newsletters, and finds creative ways to tell shorebird stories using ISS data. She holds an M.S. in Physics from the University of Arizona, and her background is in numerical analysis. Lisa is an avid birder. While living in Arizona, she coordinated the Tucson Christmas Bird Count and led field trips for the Tucson Audubon Society. She currently leads trips for the South Shore Bird Club.