Natasha Bartolotta, Tatsiana (Tania) Barychka, Tabatha Cormier, Mark Pokras, Caleb Spiegel, and Stephanie Avery-Gomm

A dead Common Loon washed on shore. Photograph by Mark Pokras.

Loons, trash, and disease. How do these three subjects coalesce into a research project involving ornithologists across North America? It all started with a simple question.

In early 2022, far from the beaches of the Atlantic Coast, researchers with the National Loon Center in Minnesota contemplated how to study the winter lives of Common Loons. Encountering two geographic hurdles–the location of the biologists themselves and the loons’ ability to be miles offshore–they turned to seeking mortality reports of loons along the coast. Together with veterinarians from Tufts University, who have conducted mortality research on breeding Common Loons in the Northeast since 1987, they questioned: How can beachgoers report sightings of loons that wash up on shore?

Much closer to the coast, biologists from the United States Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS) Northeast Regional Office in Massachusetts assembled a partnership to investigate the impact of marine debris and fisheries bycatch on marine birds and began looking for incidences of such interactions documented in reports of bird mortality along the Atlantic Coast. Historically, volunteers have helped collect such data through surveys coordinated by the Seabird Ecological Assessment Network (SEANET). Despite these efforts, many beached birds are left unreported outside of established volunteer surveys. The question remains, does the general public have an effective means to report and document bird mortality that can help biologists and managers understand sources of mortality such as marine debris?

North of the border, scientists at Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) were deep into investigations of the highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) outbreak across Eastern Canada. In the spring and summer of 2022, a mass mortality event resulted in the reports of more than 40,000 dead wild birds across formal and informal channels (Avery-Gomm et al., in preparation). To arrive at that number, ECCC collated mortality reports from federal, provincial, municipal and Indigenous governments, non-governmental organizations, academics, and two popular citizen science apps. Of those sources, how does citizen science, specifically, provide significant data toward larger datasets?

The Atlantic Marine Bird Cooperative’s Community Science & Marine Bird Health working group proposes a simple tool for answering multiple questions.

Though these biologists were separated by geography and research questions, their goals and interests were similar. They wanted to know how to gather baseline mortality data of specific species, how to investigate the impact of debris and other threats on marine birds, and how to comprehensively estimate reported mortality during a mass mortality event. The question became whether there was a wide-reaching tool that could help answer these questions. In November of 2022, the answer started to form during the annual meeting of the Atlantic Marine Bird Cooperative (AMBC).

The AMBC is an international group of resource managers, scientists, and other professionals with an interest and expertise in marine birds in the northwest Atlantic Ocean. One of the cooperative’s working groups, Community Science & Marine Bird Health (CSMBH), includes members who have a particular interest in threats to avian health, such as emerging diseases and marine debris. During the annual meeting, this working group began discussing what public tools existed for reporting bird mortalities. An idea that had already been forming among the loon researchers and USFWS biologists was proposed: to create a project through an online application that is already used by almost three million people globally—iNaturalist.

As an open-source platform, iNaturalist accumulates global biodiversity data via photo observations of plants and animals submitted from a phone or desktop device. What differentiates iNaturalist from other collection platforms is the ability to submit observations of dead animals. It also relies on a crowdsourced identification of species. As the meeting progressed, many advantages were noted about centering a project on iNaturalist. A large, motivated user base already exists, the long-term database includes mortality data, and the platform is simple to use.

Perhaps the most enticing advantage for the CSMBH working group was how easy it is to create a collection project on iNaturalist. A collection project filters existing observations based on set parameters such as taxa, location, dates, and quality grade. As long as the project is live, any new observations that meet the requirements will be automatically uploaded into the project’s records. A project could easily be formed to filter in observations of dead birds within specific taxa, including seabirds and loons, and from designated locations. Before the meeting was over, the Beached Birds iNaturalist project had taken form.

The Beached Birds project is set up to filter the iNaturalist database for observations of dead birds within one kilometer of the shoreline. Avian taxa include waterfowl, shorebirds, loons, cranes, rails, pelicans, herons, ibises, tropicbirds, grebes, tubenoses, penguins, gannets, cormorants, and allies. The project currently has a large geographic range, as some members have research interests beyond the AMBC priority region. As of September 2023, the Beached Birds project has captured more than 8,000 observations of 222 bird species submitted to iNaturalist since March 1986. Since its formation in 2008, when it began as a master’s degree project, iNaturalist has allowed users to upload historical photos as long as the general time and location are known.

Colored leg bands visible on the beached carcass of a Common Loon. Photograph by Mark Pokras.

What can we do with this information now that it’s been captured in a central project?

In October 2023, scientists from ECCC presented on behalf of the Community Science & Marine Bird Health working group at the annual AMBC meeting in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. The presentation analyzed the benefits and challenges of using iNaturalist to understand mass mortality events, focusing on exploring how well the Beached Birds project data represent the spatial, temporal, and taxonomic patterns of mortality.

For this analysis, the focus was on a subset of data from December 2021 to September 2023 in the AMBC region of the Atlantic and Gulf coasts. In this area, 469 dead birds were reported to iNaturalist, with an average of ~19 reports a month except for a spike in June 2022. Within these observations were noticeable clusters of reported mortalities in the South Atlantic, Atlantic Canada, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia.

The species most frequently observed by iNaturalist users during this window was the Northern Gannet, but other species included Razorbills, Common Loons, Great Shearwaters, Great Black-backed Gulls, Double-crested Cormorants, Common Murres, and Brown Pelicans. In Eastern Canada, a majority of these species were among those that tested positive for HPAI excluding Brown Pelicans, which are not found in Canada, and Common Loons. Of loons tested in Canada, all were negative for HPAI, with similar negative results reported across the United States—to the relief of loon biologists.

The October symposium also explored a case study in Eastern Canada. How did the iNaturalist project compare to ECCC’s collated dataset of over 40,000 dead wild birds reported from April through September of 2022? An initial analysis showed only 100 birds captured by the iNaturalist Beached Bird project during the HPAI outbreak in Eastern Canada within this time window. Northern Gannets were again the most observed species, with lesser numbers of Common Murres, cormorants, gulls, Common Eiders, and Razorbills. The list of species reported to iNaturalist mostly matched the species in the accumulated ECCC dataset, though a few highly reported species were not seen in large numbers on iNaturalist. Temporally, the uptick in observations in the Beached Birds project fell during the peak of the HPAI outbreak in Eastern Canada (June and July 2022). Spatially, however, there were some notable gaps in the iNaturalist reports.

We can now see that iNaturalist may be a tool for tracking when large die-offs of birds occur and which species are most affected. There is potential to track such events in real-time as observers can take photos with their phone and immediately upload to iNaturalist. As more people learn of the research to monitor marine bird mortality, we hope they will take a closer look on their next beach stroll for washed-ashore birds. In future disease outbreaks, a rapid increase in the number of reports made to the Beached Birds project may help alert a network of wildlife health professionals to unusual mortality events. Such iNaturalist reports could perhaps even help track down birds to collect for testing. Considering the case study in Eastern Canada, the project at this time is one piece of a larger picture. Importantly, there was some information submitted to iNaturalist that was not reported in other ways. Thus, the data collected by citizen scientists, often those witnessing events as they unfold, may meaningfully contribute to how we monitor avian health.

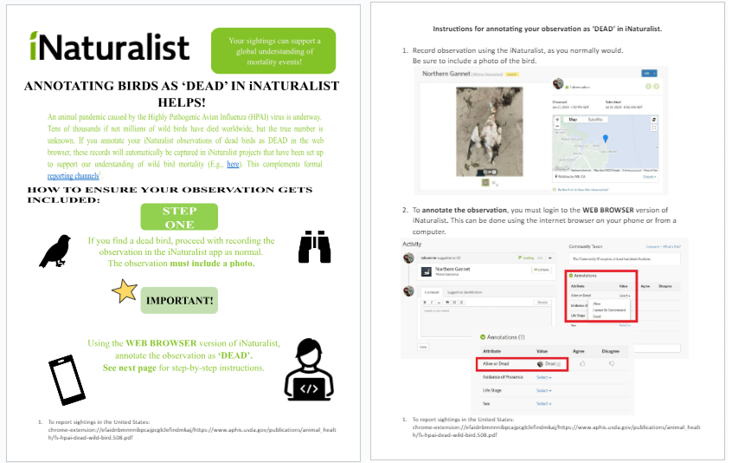

As of late 2023, however, there is a large hurdle to clear with iNaturalist when it comes to reporting dead birds. Currently, only some types of mobile phones make it possible to select “dead” as an annotation when uploading. Furthermore, even when the “dead” option is available on the phone app, this option is not displayed when uploading, so many users do not know that after submission they can—and should—return to their observations to add these annotations. The information that the observed bird was dead can be of great value, especially during mortality events and for remote areas and rare species. Instructions for how to properly report dead birds in iNaturalist via computer are shown in Figure 1 and at < https://atlanticmarinebirds.org/downloads/iNat_How_to_report_dead_birds_properly_english_CAN_USA_Nov2023.pdf>.

At ECCC, scientists went through the painstaking process of downloading more than 700 images of Northern Gannets from iNaturalist’s database for Eastern Canada and manually determined whether each of the photographed birds appeared dead or alive. They also downloaded and checked more than 800 observations from three iNaturalist users who worked with ECCC on HPAI data collection but did not mark birds as dead during their reports.

Following this dedicated effort, an additional 808 observations of beached birds were uncovered in Eastern Canada for the spring and summer of 2022. This dataset was much larger than the 100 observations initially filtered in, but it is likely still not complete. Along the entire Atlantic Coast, there are probably still hundreds of observations not included in the project, all because they are not marked with the “dead” annotation. So, for groups monitoring the mortality of a specific species such as Common Loon, the iNaturalist project requires additional effort to uncover all the data. Just as ECCC scientists did, analysts will need to manually check all observations of the species to identify any dead birds that have not been correctly annotated and therefore have fallen through the proverbial cracks. Once this annotation is done, researchers can more thoroughly consider the use of iNaturalist in monitoring the baseline mortality level of wintering Common Loons on the Atlantic Coast.

Figure 1. Guidance on how to annotate birds as ‘dead’ in iNaturalist, prepared by Environment and Climate Change Canada. See <https://atlanticmarinebirds.org/downloads/iNat_How_to_report_dead_birds_properly_english_CAN_USA_Nov2023.pdf> for a higher resolution image.

There is a treasure trove of data in iNaturalist just waiting to be closely combed by a patient and curious individual.

iNaturalist is based on providing images. Could the photos themselves reveal the cause of death, perhaps by showing possible causes such as marine debris or entanglement? More importantly, how can one track that information within iNaturalist so that it can be used by biologists like those at the USFWS who are monitoring impacts of different sources of mortality on marine bird populations?

Customizable “observations fields” are a lesser-known feature of iNaturalist. Such fields are often used by particular projects to collect relevant metadata, for example to tag images with specific attributes such as leg bands, debris, habitat, food sources, or predation. The challenge with the observation fields, as with the “dead” annotation, is that users must know that the observation field exists and that they must intentionally return to their observation post-upload to select this information. The solution may be in training iNaturalist users to use this feature to track things like marine debris. It may also be possible to recruit volunteers to comb through the Beached Birds project and edit observation fields on existing records.

How to get involved

The future of the Beached Birds project is promising. As it grows and more iNaturalist users learn of its existence, it will become a valuable, long-term citizen science project to monitor marine bird health, disease, and survival. Those interested in getting involved can make an account and start submitting their beached birds observations right away. Of course, users must not forget to select the “dead” annotation after upload (Figure 1). Once the annotation is made, the observation will automatically be filtered into the Beached Birds project and the data will contribute to ongoing research coordinated by the Atlantic Marine Bird Cooperative’s Community Science & Marine Bird Health working group.

For those who are already avid iNaturalist users, consider joining the project with your iNaturalist account to explore existing observations. From home, you can aid this research by providing identifications on casual-grade observations, checking and verifying species identifications, marking photos with evidence of marine debris, and, for the especially motivated, perusing all observations of birds along the Atlantic and Gulf Coast to check for those missing the all-important “dead” annotation. You can find more information about the project at www.inaturalist.org/projects/beached-birds, and learn more about the Atlantic Marine Bird Cooperative at www.atlanticmarinebirds.org.

Natasha Bartolotta is the stewardship & outreach manager at the National Loon Center in Minnesota and a member of the iNaturalist task group for the Community Science & Marine Bird Health working group.

Tatsiana (Tania) Barychka is a conservation ecologist and research scientist with Environment and Climate Change Canada. She is responsible for the data management and analysis of the spatiotemporal and taxonomic trends in waterbird mortality associated with the highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (H5N1 2.3.4.4b) outbreak in Eastern Canada.

Tabatha Cormier is a wildlife biologist working with Environment and Climate Change Canada. She is a member of Stephanie Avery-Gomm’s team working on the assessment of mortality observed in wild birds caused by the highly pathogenic avian influenza virus in Eastern Canada in 2023 and comparing observed mortality this year to the mass mortality events in 2022.

Caleb Spiegel is a marine bird and shorebird biologist for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Migratory Birds Program and the coordinator of the Atlantic Marine Bird Cooperative. He works with partners to develop and coordinate conservation, management, and research projects in offshore, nearshore, and coastal environments.

Mark Pokras is a semi-retired wildlife veterinarian and emeritus associate professor at Tufts University’s Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine, where he directed both the Tufts Wildlife Clinic and the Center for Conservation Medicine. He has been involved in studies of aquatic bird health for nearly 50 years.

Stephanie Avery-Gomm is a seabird biologist and research scientist with Environment and Climate Change Canada. As the coordinator of the Atlantic Marine Bird Cooperative’s Community Science and Marine Bird Health working group, she is leading the assessment of mortality and population-level impacts associated with the mass mortality event in Eastern Canada caused by the highly pathogenic avian influenza virus H5N1 2.3.4.4b.